“I Won’t Be Misrepresenting Anybody’s Life Experience But My Own.” A Conversation with Cartoonist and Comedian Luke Healy

The Author of The Con Artists Talks to Connor Ratliff

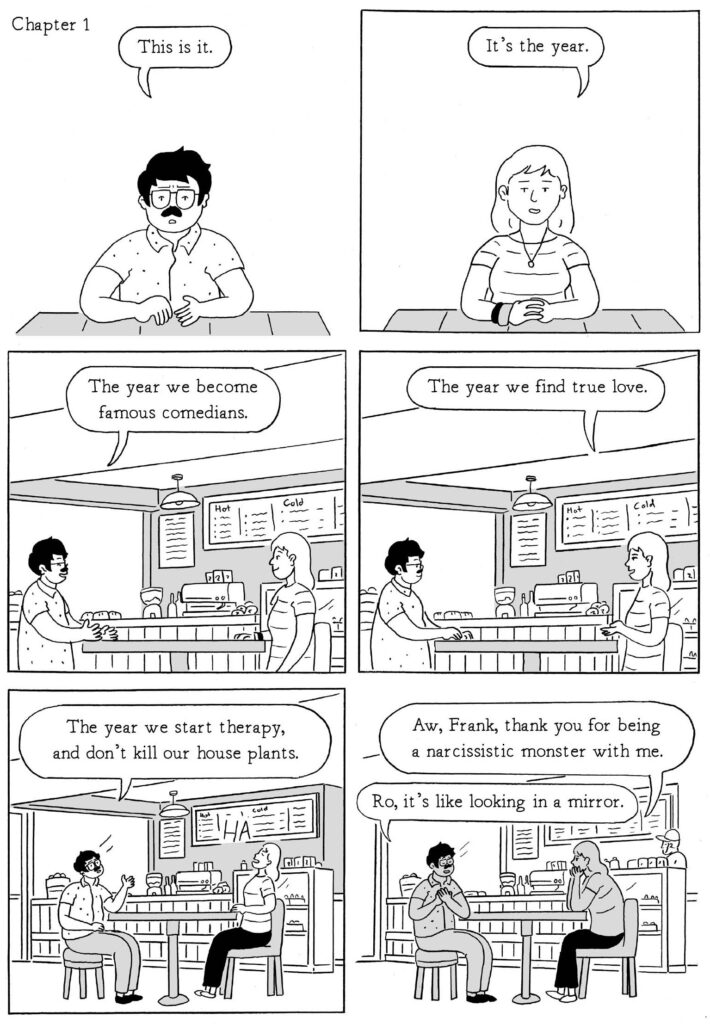

Cartoonist and comedian Luke Healy (The Con Artists, Americana) and actor Connor Ratliff (Dead Eyes) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a spring event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The conversation revolved around Healy’s new book, The Con Artists, which follows two aspiring comedian friends who are struggling to find their path to fame amid the pitfalls created by anxiety and social media.

The two comics spoke about different forms of comedy, the ethics of art versus journalism, and how semi-autobiographical work can lead to a deeper understanding of oneself.

*

Connor Ratliff: I was fascinated to learn that you began The Con Artists process with a book where you were documenting teaching and performing improv comedy. You’re someone who does both improv and stand-up, which are two very different comedy disciplines. In some ways, the fact that you ended up with a book about stand-up is a complete 180 from a book about improv.

Luke Healy: It is so hard to capture improv in writing. Even recorded improv doesn’t have the same feeling of being in the room.

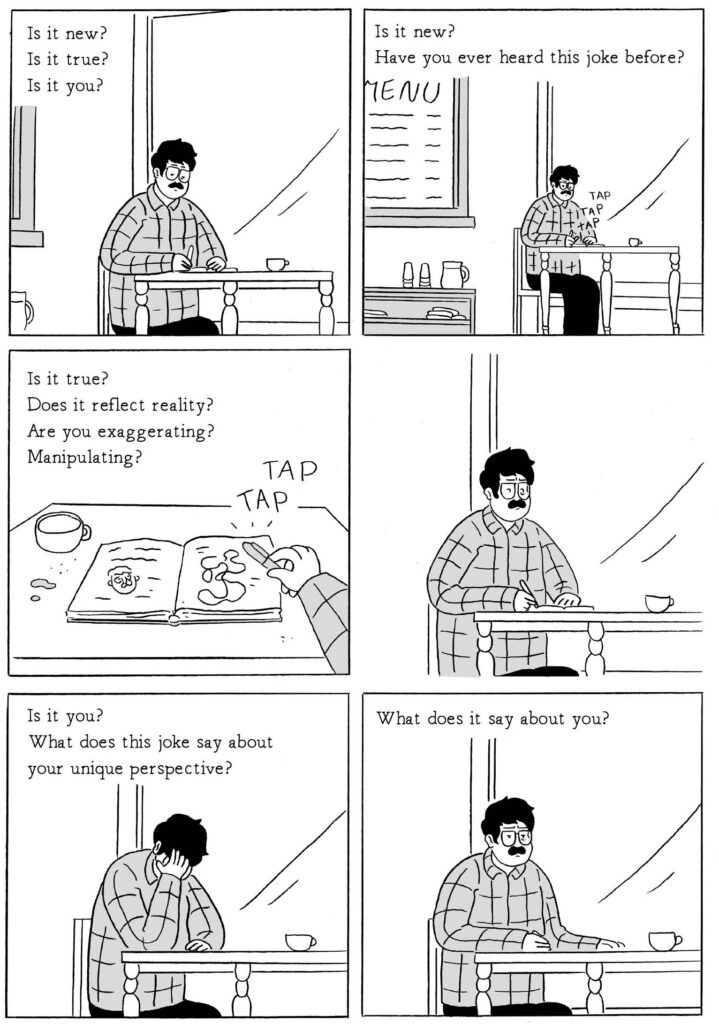

CR: It made sense to me that the novel ultimately became about stand-up, because improv is a collaborative and social medium. Even a successful and confident stand-up is alone, and the image of someone alone on stage matches the mood of the story you’re telling. A large part of the book is the main character feeling isolated due to his thoughts and fears. The fact that the thing he does for fun is isolating himself in front of a crowd, works really well.

LH: A lot of the book is based on real events, and I do feel lucky that when those things were happening to me, I was doing improv all the time and got to be around people who were silly and supportive. But the imagery of stand-up is very rich.

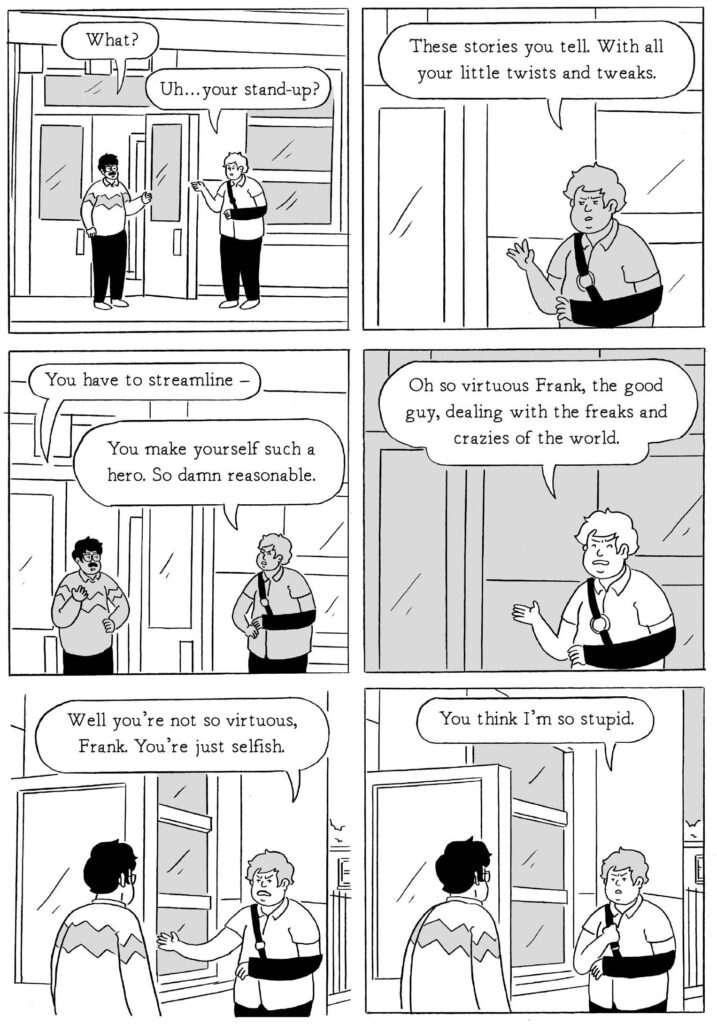

CR: Even the purest of nonfiction is coming from a point of view. There’s always some element of selecting which information is presented in what order, but there’s that slippery slope of ‘based on a true story’ versus completely fictionalized.

When you’re making those choices, what are your initial thoughts on what to keep, what to invent, or what to alter?

LH: One of the questions the book asks you to consider is what is or isn’t true. I studied journalism for undergrad, and I was a really bad journalist. I just didn’t have the confidence for it.

But I draw a very hard line about calling something nonfiction—for me it needs to be as close to my recollection of reality as possible. If it’s embellished at all, I prefer to classify it as fiction, which is why this book is largely classified as fiction. I had this big crisis concerning writing about other people’s lives. If I’m writing about myself and subconsciously or accidentally altering stuff, it’s just about me and I won’t be misrepresenting anybody’s life experience but my own.

CR: The blending of art and journalism is an interesting thing in terms of ethics. The ethics of art are very different from the ethics of reporting. When we see comics dealing with nonfiction, the disclaimer is almost embedded in the medium. It’s drawn out, so one layer of liberty is already being taken.

LH: What I really like about nonfiction comics is that you can see the artist’s hand, almost literally. You’re seeing marks they’ve made with their hand. It’s apparent that it’s from one person’s point of view.

CR: At the beginning of The Con Artists, you present yourself as totally clean shaven, and then you put on the mustache as if it’s a costume piece, which is a lovely device. I always find it easy to draw myself, because as long as I have the beard or my glasses, those basic shapes convey a character. You don’t actually have to get the nose or the mouth right.

LH: The best thing about cartooning for me is the simpler, the better. All you need is one distinguishing feature. All of my characters look practically identical, except the one that represents me has dark hair, in all my books.

CR: When you’re writing books where you appear as a character, do you have aspects of your personality that you choose not to include in your comic persona?

LH: There definitely are things that I’ve never written about. I don’t write about romantic relationships, because that feels like writing about somebody else in a very intimate way.

In The Con Artists, the other main character Giorgio, is by far the most intimate portrait of another person that I’ve ever included in my work. I always try to keep it from the lead character’s perspective, where everything that happens is a reflection of them, and you never truly get to know the other characters. The real relationship is between the reader and me. That’s the truly intimate relationship.

I’m a pretty repressed guy—I grew up in Catholic Ireland in the 1990s, which wasn’t the best place for talking about your feelings. I have a hard time expressing how I feel about very difficult, traumatic events. But if I write 200 pages telling you what happened, then maybe you’ll understand how I feel.

CR: A scene that jumped out at me is when Giorgio says, “These stories, you tell with all your little twists and tweaks, you make yourself such a hero, so damn reasonable.” And he reads you the riot act on the way you present yourself. When you’re writing something like that, how much of it is drawing from your own self-criticism versus a real incident where someone read you the riot act?

LH: That’s pretty much all self-criticism. When I started writing that scene, I was like, “I need to spell out to the reader that writing this book makes me a piece of shit.” But that’s letting myself off the hook, and putting it in was more exposing, because you can’t just acknowledge that and be absolved. The actual noble choice is to stop making this book, give back your advance and move on with your life.

CR: In the book, there are scenes where the characters are telling their jokes before an audience. Do you use your own jokes to shape these sequences?

LH: The character who functions as a stand-in for me uses material that I was doing before COVID. The other stand-up who appears in the book, Ro, is based on a friend of mine, Laufey Haraldsdóttir, and she’s an Icelandic comedian. Ro’s stand-up is me parodying her real standup, and so it was a fun thing to write what she would do, but gently rib it as well.

CR: Whenever comedians are able to nail another comedian’s act or imitate it in a funny way, it’s always one of the most endearing things to me.

LH: It’s a sort of compliment. It’s a devastating compliment because it means you have a clear enough voice that someone can imitate it, but it’s not nice to feel seen.

CR: How was your experience formally studying comics? Would you recommend it?

LH: I had a really good time and I would recommend it to some people. In order to get the most out of it, you have to be really self motivated and self-directed. I went to The Center for Cartoon Studies, which is a great program and I really loved it. Because it was a big deal for me to get to live in America and go to this school, I really, really tried to make the most of it.

CR: How long did it take you to develop your style, and do you feel like it’s still evolving?

LH: Even the book I’m working on now is so different from The Con Artists in a lot of ways. So yeah, always evolving. I think it took a good five years before I made anything that I liked.

CR: What’s next? Are you working on anything new?

LH: I’m working on a new book called Selfish. It’s a fake memoir of the next 20 years of my life, about me being a narcissist and caring about my career while climate change destroys the Earth and floods every major city. Meanwhile, I’m like, “Will I work again?”

CR: How do you recover from art block and get back into the groove of drawing comics?

LH: Make short and really bad stuff. I’m a terrible perfectionist and my big problem is often getting started. Just sit down and purposefully make the worst comic you can, but finish it. If you try to make something horrible, by the end, you’ll want to make something good.

_______________________________

Luke Healy’s The Con Artists is out now from Drawn & Quarterly.