I Was Almost Svetlana Alexievich's Translator

Laura Esther Wolfson Falling Short of Literary Fame

I’d been earning my living as a Russian-English interpreter for a decade and a half when I was hired to give English voice to one Svetlana Alexievich, an author slated to appear at the 2005 PEN World Voices Festival in New York City, where I live. I’d never heard of her; back then, few in the West had.

I learned as I prepared for the assignment that she was a former newspaperwoman whose books were based on interviews she did with plain Soviet and post-Soviet folk about their experiences of calamities such as World War II and the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Most recently, she had traveled to Chernobyl, borne witness to the consequences of the nuclear disaster, and then reported back, conveying in the locals’ own words their grotesque sufferings and also those of the first responders, ordinary firemen sent into the fray in their shirtsleeves, absolutely innocent of radiation safety training or expertise.

The Russian language lacks a term for oral history, and so, with refreshing disregard for the sometimes heavily fortified border separating fiction from nonfiction, Alexievich had come up with her own, calling her books “novels in voices,” or simply “novels.” This despite the fact that their content came verbatim from taped interviews, had no narrative through-line, and swapped in a new protagonist every couple of pages. In addition to my day job with the Russian language, I was also trying to make a mark as a writer. Having toiled obscurely and intermittently for years in a difficult-to-name genre containing generous helpings of the lived, the observed, and the overheard, I instantly appreciated her confident blurring of distinctions that had long struck me as artificial and unnecessary.

Svetlana came from Minsk, the capital of Belarus, one of those new nations then poking up through the rubble of the Soviet Union. Her country was widely known as the last dictatorship in Europe. When I met her, she was persona non grata back home, having disgruntled the authorities somehow. She’d been living out of a suitcase for years, bouncing from one Western European capital to another, getting by on grants and gifts.

She was a small, sixtyish woman, shy, unpretentious. Her manner of speaking was urgent and heartfelt.

“For days after the blast at Chernobyl,” she said at the festival, and I interpreted, “the bees stayed inside their hives. The worms burrowed a meter down into the ground. Those little creatures knew what to do. But what about us? What did we humans do? As always, we watched TV; we listened to Gorbachev; we played soccer.”

Speaking of her genre and how she came to it, she said, “For us Slavs, talk is paramount. Life’s mysteries are what we discuss. What is the essence, the core? As I sought my literary form, I came increasingly to understand that what I heard in the crowd was far more powerful than anything I was reading, and more affecting than anything that might flow from the pen of a solitary writer. Nowadays, one single person cannot write the all-encompassing book, as Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy used to do. The world has grown far too complex. But within each of us there lies a text: maybe two sentences, maybe half a page, maybe five pages, and these could be compiled into a joint opus. I realized that my books were in fact lying scattered about on the ground. I had only to pick them up.”

Channeling her simple eloquence, I felt both euphoria and melancholy. My peculiar, fleeting intimacy with this remarkable woman and the interior of her mind seemed to place me on the cusp of something marvelous. Yet this sense that the best was yet to come was usually an illusion—I knew this. The climax was here; it was now.

She finished speaking; an instant later, I finished, and the main event was done. Over cheese cubes and wine in plastic cups in a rapidly emptying room, a few audience members praised my work effusively. For one moment, I thought that this heady praise was the very miracle I’d felt coming on.

Then I caught the number three train uptown. Full stop.

Except that Svetlana then passed my name to her agent, who passed it to a boutique publisher in the Midwest, who, some time later, approached me to translate two of her books into English.

*

I’d been a Russianist practically forever. I’d laid the groundwork in college, studying conversation, grammar, and literature, later honing my knowledge through total immersion behind the Iron Curtain, reading, movies, and, most important, long, long talks with native speakers from all walks of life. I’d translated books; I’d interpreted for statesmen and scoundrels, who were not infrequently one and the same; I’d devoted my working life to this language. You would think that my relationship with Russian, its writers, and its literature would be one of uncomplicated affection and intimacy.

But no. By my late thirties, my ties to Russian language and culture were growing increasingly tenuous. I had left my Russian-speaking husband years before. I had not set foot in Russia or its satellites in nearly a decade and had no plans to return. (As it turned out, I would go to Lithuania a few years later, but I didn’t know that then, and that trip was unrelated to my work as a Russianist.)

I still spoke very fluently, however, for my immersion, dating to my twenties and early thirties, had been deep. Through the medium of Russian I’d learned crucial, cruel truths. In Russian I had fallen in love, and out. Despite my foreign accent and lapses grammatical, lexical, and cultural, Russian had in this way become almost native to me, as a close friend may become family, absent any tie of blood or marriage.

But that lingering fluency notwithstanding, I was now drawing down credit accumulated years before. Like some exiled Russian countess selling off the last of the emeralds and pearls sewn decades earlier into the hems and seams of her underthings, I was living off diminishing reserves, doing little apart from my daily work to replenish my storehouse of knowledge.

My initial reason for learning the language had been to read Russian literature in the original. Since freshman year in college, in response to the oft-repeated question, why Russian? I’d invariably replied that, having read Anna Karenina in English at age 14, my aim was to take her on in the original, vaulting clear over the heads of Constance Garnett, David Magarshack, and the rest of the literary translator pack.

But somehow, learning Russian had distanced me from Russian literature. It no longer made any sense for me to read the Russians in translation. Learning Russian had been painful—imagine your brain taken apart like a wristwatch, then reassembled, with a few parts left over that no longer fit anywhere. Choosing a translation over the original would strip those sufferings of all meaning. However, approaching Russian literature in the original was still daunting. And so, having devoted years to learning Russian, I now found myself in a limbo nearly devoid of Russian literature. It was as if I had scaled Mount Everest and was failing to take in the view—except during rare bursts, when, somehow mustering the strength to ignore my anxieties, I would binge-read in Russian for a few weeks. In this way, I fell in love with Pushkin, Chekhov, and Tolstoy, and, with time, built up the stamina to traverse vast tracts of Dostoyevsky.

But it took me years and years—well over a decade after I finished college—to make time for the unmediated Anna, and by then, it was not the same book I’d read at 14. No longer was it the story of a fetching woman, the flush of new love rendering her more fetching still, as she mazurkaed in the arms of a dashing suitor at an elegant ball. Now it was about that same woman’s corpse laid out for identification in a railway shed, a cold sneer on her stiffening features; it was about men volunteering headlong for the Serbian-Ottoman War in order to flee their disastrous personal lives. This change was not, I think, due to the chasm that sometimes yawns between original and translation.

And of my total reading, Russian literature remained a very, very small part. There were great swaths of it that, at this rate, I would never know. During my years spent among the Russians, I had grown used to hearing people say things like, “Last year, I reread all of Russian literature,” and this was actually conceivable, for, as Nabokov says early on in Lectures on Russian Literature (written, of course, in exquisite English), “the beautifully commodious thing about Russian prose is that it is all contained in the amphora of one round century—with an additional little cream jug provided for whatever surplus may have accumulated since.”

But it was still too much for me.

*

The festival people sent a book of Svetlana’s my way to help me prepare, an English translation called Voices from Chernobyl. The festival was coming up too quickly for me to lay my hands on the original, so I broke my no-translation rule.

A few pages in, I was jarringly reminded that reading translations from a language you know can be downright annoying. The errors are plain to see, even without the original close at hand. And a decade later, one mistranslation in that book haunts me still. Some of the first responders, away from home for months, frequented a brothel near the reactor. According to the translation, the “girls” from the brothel willingly went for walks with them, even though the men had been irradiated through and through.

Now, the Russian word gulyat’, “to take a walk,” has a second, more colloquial meaning, vague yet suggestive, covering acts that range from promiscuous to debauched, and including sprees, binges, and escapades of all kinds. Clearly, the girls from the brothel had gone for much more than walks with the doomed emergency workers, but this was lost on the translator; Russian-born, he had left behind the land of his birth and his first language at age six, too young of course to grasp such meanings.

Nor, it was clear, had the publisher provided much oversight. Translation deeply affects a reader’s relationship to any book originally written in a language she doesn’t know, yet the boutique house responsible for Voices from Chernobyl apparently felt that such concerns hardly warranted much effort or expense.

No matter: the book gave me a general sense of Svetlana’s work, which was what I needed to do the job.

*

I was in the middle of my life when the festival people started calling me to work with Russian-speaking authors—Svetlana was not the only one—and my life was falling apart. This was just after I’d been diagnosed with a degenerative, sometimes fatal pulmonary condition. Twice I had been hospitalized with a collapsed lung, and I was in evaluation for a double lung transplant. I had begun sleeping with an oxygen tube in my nose and was so short of breath that I could barely climb a flight of stairs or walk up a gentle slope.

In the face of serious malady, everything crumbles. Simultaneous interpreting being nearly as much about lung power as about language, I was increasingly unable to work. My debts were mounting. My health insurance coverage, which had over the years run the gamut from skimpy to nil, was tilting once again toward nonexistent.

Despite the coughing, weakness, and shortness of breath that were now a regular part of my days, I believed I could still do the festival gigs, which involved standing before large audiences alongside authors who represented the cream of contemporary Russian literature and instantaneously putting their utterances into English. And do them I could—if I spent the day in bed both before and after, and drove myself mercilessly the day of—for they lasted only an hour or so. When the author paused in thought, I sneaked a deep, deep breath and let it out, puff by puff: invisible smoke rings made from air.

And so, for years after I had to decline all other offers of interpreting work, I continued to accept the festival gigs. They were a narrow bridge between my career as an interpreter, which was slipping from my grasp, and recognition as a writer, which I might never attain. For, on top of everything else, I was 40 years old and had published not one single book of my own, only translations of other people’s books. The festival gigs allowed me to hold forth about writing before a rapt crowd, even if the words I uttered were not my own, even if the admiration I basked in was not meant for me.

Plus, they brought in some needed extra cash.

*

Svetlana stayed in touch. Following the festival, she mailed a postcard from Paris and soon after that, a copy of Boys in Zinc, her book on the Soviet war in Afghanistan. On the flyleaf, she thanked me for my work at the festival, spoke of collaborations to come, and urged me to be happy, in spite of everything. A decade later, this untranslatably Slavic phrase remains mysterious to me.

I do not remember now if Svetlana in fact knew that I had translated books before, or if she innocently assumed that my ability to translate her spoken words meant that I would also be able to put her written words into English. Although the words “interpreter” and “translator” have become hopelessly confounded in the popular imagination, the work of the interpreter, who renders speech in one language into speech in another before a live audience or for broadcast, is in fact a far cry from that of the translator, who carries the written word over from one language into another while seated alone at her desk. One is not more difficult than the other; they are simply difficult in different ways.

“I’d translated books; I’d interpreted for statesmen and scoundrels, who were not infrequently one and the same; I’d devoted my working life to this language. You would think that my relationship with Russian, its writers, and its literature would be one of uncomplicated affection and intimacy.”

I had tried for years to make my way in the world of literary translation but had repeatedly gotten sidetracked into translating other things—works of history; monographs on archaeology and philosophy; proposals to address needle-sharing in Kazakhstan, prostitution in Uzbekistan, the resurgence of polygamy in Tajikistan; phone tap transcripts of New York–based Russian organized crime suspects. (“How great to be in America and know we’re not being bugged!”)

I had gravitated toward literary translation in part because I hoped it could provide some writerly grati cation, minus the risk of failure that shadows every attempt at translating the world into words. As I imagined it, I would spend engrossing hours sculpting sentences, and my name would appear on a title page, perhaps even a cover, but with none of the angst that comes of waiting, waiting for the next word to emerge from the void.

However, despite a few modest translation publications and a prize or two, it was not really working out. The good books and the interesting writers were going to other translators.

*

In the time before Svetlana, an eminent literary translator once got my number from somewhere and called in a panic. Her computer had swallowed ten chapters of a major glasnost-era novel that she was putting into English; the publisher was breathing down her neck; could I translate the missing piece, and could I do it right away? But I must not tell a soul, for the author, a dear friend of hers, would be terribly wounded if he learned that she’d farmed out a chunk of his masterpiece.

I knew this book as well as it is possible to know a work you’ve never read. My excuse, this time, was that the great poet Joseph Brodsky had famously dismissed it as makulatura, which literally means “old newspaper” or other dated paper goods fit only for the recycling bin, but can also mean something approximating “pulp fiction,” only a whole lot less racy. It was about a band of Stalin-era university students, once close friends, later flung apart by history, with some rising to positions of power and deciding fates, while others were dispatched to the gulag.

When the book came out to great fanfare in 1987, I’d picked up a dozen copies at the hard-currency store in Moscow and, barely glancing at it myself, handed them out to Russians I knew. For, while it had not come under the censor’s axe (if there still was a censor; this was one of those recurring murky periods in Russian history when no one quite knew what was going on), neither, for obscure reasons having to do with the vagaries of Soviet supply and demand, was it commercially available to ordinary Russians. It was such a hot ticket in Moscow that season that one day, upon returning to my hotel room unexpectedly in the middle of the afternoon, I walked in on three chambermaids sprawled across my bed, their frilly little aprons all askew, feather dusters forgotten on the floor, each one leafing through a copy of the book from the pile on the nightstand.

Now I agreed to translate lost chapters 23 through 32, encouraged by hints that this might lead eventually to other work that I could openly claim as my own. The deadline was so tight that I worked from a sheaf of xeroxed pages without seeing the rest of the book, for those chapters were the only ones provided, and I had given away my last copy years before. The respected literary translator massaged my bit to achieve a stylistically seamless fit with hers (and perhaps, it now occurs to me, with those of other subcontractors as well). She paid promptly, and when the translation came out, it landed in my mailbox, her name emblazoned across the cover beneath the author’s, in a slightly smaller font. As expected.

After that, there was not another word from her, ever.

*

Eventually I would conclude, after hearing other translators’ stories, that the best way to become a translator of contemporary literature is not to do uncredited work on behalf of a translator with a big name and few scruples, but rather to fall in with a bohemian crowd when you’re in your twenties, sojourning in some foreign land and soaking up your chosen language.

You start translating as an act of friendship. One obscure, struggling novelist who drives a cab passes you on to another who works as a night watchman, who refers you to an unemployed poet who lives with his mother, and on and on. And if your bohemian pals form a rock band and you get roped in as the drummer or the lead singer, why, all the better, even if the group splits up after just a gig or two, for the shared experience would forge a close bond.

There are people who do this sort of thing and go on to translate entire schools or generations of contemporary authors in obscure Balkan or Slavic countries, some eventually settling and starting families there. You have to keep at it for years, though, doing without remuneration stuff that two or three decades on will make for delightful tales of a madcap youth, until your bohemian friends (well, a few of them, anyway) mature into acclaimed authors, sweeping you along with them, and you all become over-night sensations.

But what if you choose the wrong bohemian crowd? What if their creative strivings come to naught? God knows, it happens every day. We stride backward into the unfurling of time, blind to whatever is bearing down, and so such decisions must always be entirely uncalculating.

*

About a year after I worked with Svetlana at the festival, I landed a job in East Midtown, translating diplomatic correspondence and reports from Russian and French into English. (In a gamble that paid off, I charged the expenses associated with learning French for the job, including the stays in Paris and Montreal, settling the bill after I was hired.)

Passing a door left ajar, I would sometimes glimpse a senior colleague, hunched and Gogolian from decades in the international civil service, brandishing a crumbling typescript entitled Instructions for Translators and railing at some cringing junior translator about their errors: incorrect initial capitalization of treaty names, say, or a stray reference to “England” instead of “the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland” or failure to follow the house rule of inserting the standard closing for diplomatic correspondence (“Accept, Sir/Madame, the renewed assurances of my highest consideration”), regardless of what sentiment the original might express.

Sometimes I was that junior translator behind the door. Having worked independently nearly forever, I was unaccustomed to such treatment and did not accept it with good grace. But the job paid more handsomely than anything else I’d ever done or might hope to do.

Plus, it came with health insurance.

*

As I was settling into regular employment, the boutique Midwestern publisher sent along some pages from two of Svetlana’s books that were as yet untranslated. Naturally, they wanted to see my work before signing a contract for the translation, and I, too, needed to know if I could inhabit the books daily, intimately, contentedly, for the years the work would take to complete.

On a night soon after the pages arrived, I struggled up the stairs from the subway, stopping as usual at the top to pant a while, then made my way slowly home through the wintry dusk, pausing frequently to force the air in and out of my cold-stiffened lungs. After dinner, I sat down at the computer to tackle a section about Soviet women who had seen combat in World War II.

I was immediately transported to the front lines.

A nurse dragged two wounded soldiers from the battlefield, bullets whizzing overhead in the pitch-black night. She moved one of them toward the infirmary tent, set him down, and returned for the other. When the moon emerged from behind a cloud, she saw that one of the men wore a German uniform. She hauled him to safety nonetheless, and bound up his wounds.

“We tended to the enemy wounded, we Soviets did,” she told Svetlana with modest pride.

A man recalled his role in the Soviet occupation of Germany late in the war. “Sometimes, there would be ten of us servicemen to one German girl,” he said. “Ten men, one girl,” he repeated in disbelief. “I was a good boy, from a cultivated family. To this day, I do not understand: How could I do this?” He paused. “We never, ever spoke to the girls in our unit about what we did. Oh, no. They were our comrades.”

A young woman returned home when the fighting was over. At dawn, while everyone else in the house still slept, her mother shook her awake.

“The whole town knows where you’ve been,” said the mother. “People have heard what you soldier girls got up to in the trenches with the men there. How will your little sisters find husbands if you stay here with us?”

She thrust a bundle at her and a heel of bread wrapped in newspaper.

“Daughter of mine,” she said, “you must leave and never come back. Now, go.”

*

I lavished hours on these brief passages. The words were simple; my dictionaries lay unopened. But each section had its own voice; every few pages, there was a new speaker, with a new idiolect. Each little segment had to sound exactly right.

As I translated, I pondered the changed contours of my days. Everything that mattered—my own writing, which I’d begun to approach with greater seriousness; the myriad details of managing a chronic illness, in itself a second job—had to be crammed now into a few hours a week. In the old, carefree (and nearly penniless) freelance days, I could have translated Svetlana by daylight. Now she too must be relegated to after hours.

I finished the pages and set them aside. Returning to them a few days later, I was dismayed: What had I done to Svetlana? Everything in my rendering was correct, yet none of it was right.

It struck me anew how ill-matched Russian and English are. So many Russian sentences lack an identifiable grammatical subject. Who is performing the action? This makes perfect sense in the Russian-speaking world, where impersonal forces have held sway since time out of mind, deciding fates and disposing with impunity of small and impotent beings.

In English, this leads to incomprehensible gaps. Yet if the subject was left implicit in the original, who was I to put a name to it in the translation? In Russian, everyone understood who was doing what. Hints were rife; unspecified connections were mysteriously clear. But what read as compelling and merely elliptical in Russian became, in English, a loose bundle of irrelevancies and non sequiturs. In Russian, there was a deep, narrow well of unuttered meaning in that small white space between the full stop at the end of one sentence and the uppercase letter that began the next. I might tumble into one of those wells, never to reemerge.

I declined the project, pleading health problems.

The years were whipping past; now I was in my late forties. At the job, the pay mounted and the miseries diminished, though at first these shifts were slow, verging on imperceptible. Financial security took hold. The lung disease, degenerative, slowed its advance, thanks to a wildly expensive little pill now covered by insurance. This pill, yellow, triangular, and puffy, like a tiny, magical sofa cushion, kept me off the transplant list, and maybe even—for who can say what might have been? —off the obituary page.

This newfound stability enabled me to spend hours each week putting my own words to paper and to send out my work (first-person stories, taken more or less directly from life) for publication. My own work—not translations, but originals—began appearing regularly in respected literary magazines. Although I expected every publication to be my last and was certain that my success as a writer would always be exceedingly modest, setting aside literary translation for writing seemed to me the only possible choice.

From time to time, my thoughts turned to Svetlana and to that opportunity I’d passed up. I imagined that the publisher must eventually have found someone else to translate the books. No doubt they were out there somewhere, in English, seeking their readers.

And then, nearly a decade after I had declined to translate them, I discovered that those books of Svetlana’s, which I’d come to think of in some way as mine, were still unavailable in English, and that despite that fact, the London bookmakers had for several years been placing odds on her for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

A Nobel for oral history? It seemed unlikely.

*

According to the press reports, when Stockholm called, Alexievich was in the kitchen, doing her ironing. She said she’d use the prize money to buy her freedom. She had two more books in the works, one about aging and the other about love, both of which needed her sustained attention.

Ironing. Laundry. Could it be true? If so, that utter simplicity I remembered from a decade ago was unchanged. I imagined the small puffs of steam belching upward, the mounting piles of warm, smooth linen on the kitchen table. Did she use a modern iron with an electric cord, I wondered, or one of those cast iron ones that you heat on the stove, the kind that has no cord, yet is not cordless in the way we use that term now?

I am familiar with those irons that you heat over the gas. My ex-husband’s grandmother, who witnessed at close hand many of the depredations of the 20th century, who took in her younger brother, his health broken after ten years in the gulag for stealing a bottle of vodka on a dare, and nursed him until he died—my ex-grandmother-in-law, her nostalgia for the Stalin years palpable and intact, held on, God knows why, to several of those early 20th-century, sharp-edged, pointed, heavy hunks of black metal.

They came in handy on the occasions, increasingly frequent around the time of Communism’s collapse, when the power would go out in the capital of Soviet Georgia, leaving us in the dark sometimes for nights on end. We never knew exactly why the power failed, only that it added to the general sense of apocalypse. The night before we married, she brought out those irons, heating them on the gas, and we pressed our wedding clothes by candlelight.

I can no longer ask Alexandra Pavlovna, whom I knew as “Bobbo” (Russian for “Granny”), why she saved them. I suspect she knew their time would come around again. Or perhaps, because she’d known deprivation—she’d lost a sister to starvation in the Siege of Leningrad, then taken in the tiny, motherless girl left behind—she was incapable of throwing away a stale crust of bread, let alone perfectly serviceable household implements.

Svetlana is of course far younger than Bobbo, but she’s seen plenty too. She too might have such irons stored on a high shelf, handed down, perhaps, from her mother. Her mother, who, according to the press, had been a country schoolteacher.

*

I lose myself in these musings so as not to batter myself with recriminations over the Nobel. My approach, honed over years (more than a decade now) of chronic illness, is my own blend of acceptance and denial. It is not good to dwell on what might have been: the participation in something meaningful, the inherent satisfaction, and yes, the honor and prestige, and perhaps a modest financial windfall—these could-have-beens, catalogued here from most important down to least.

Who in our culture, where celebrity equals godhood, would not want to be this close to glory? To deny this would be disingenuous. For there must be few things more miraculous to witness at close range or to live through than that instant when the light falls on something long swathed in shadow, washing it golden and bestowing worldly sense upon years of toil and obscurity. Walking backward as we do into whatever awaits, we never know whether or when this will happen. Or how. Or why.

*

All the reasons I declined: I remember them well. They were valid back then, every single one, and none of them had gone away in the meantime. Yet trying now to turn back the clock, I chased the assignment, worked my old contacts, sent off translation samples to agents and publishers once again. This was shameless, I knew, and I also knew that jumping on the bandwagon now, even if I was successful in doing so, would afford nothing like the delight that would have been mine had I simply accepted the translations when they were offered and awakened years later to the fruity, rounded tones of National Public Radio announcing Svetlana’s triumph.

I barrel through Alexievich’s books now, one after the other, all five, without surfacing in between. In all my life, I’ve never read so many Russian books at one go, and the more I read, the more I crave. I cling to these books; they keep me afloat through days of office work and shortness of breath. Over solitary meals and on the subway I imbibe them, in the bathroom, and in bed. Her ability to bring readers into proximity with people and situations utterly removed from their day-to-day lives—this is the real thing. For the weeks it takes me to read them, they become the point of my existence, though, objectively, what they offer has little to do with me.

For what have I in common with the mother of a veteran of the Soviet war in Afghanistan whose son returns from the war so traumatized that she procures prostitutes for him and even becomes, as she delicately puts it, his mistress for a night? Later, he does a Raskolnikov, committing a random murder with a meat cleaver borrowed from her kitchen, and where once she waited years for him to come home from war, she now travels long distances to visit him behind bars.

“For there must be few things more miraculous to witness at close range or to live through than that instant when the light falls on something long swathed in shadow, washing it golden and bestowing worldly sense upon years of toil and obscurity.”

And what have I in common with the Soviet patriots in Alexievich’s books, admirers of Stalin who, speaking into her omnipresent tape recorder, rue the passing of Communism, report that they continue each year to celebrate with gusto the anniversary of the October Revolution, then segue into tales of the beatings they endured in KGB cellars; the weeks or months they spent en route to remote prison camps, upright in jammed cattle cars with no facilities but an overflowing bucket in the corner; the loss of a wife or a father or ten to twenty years of their own life to the gulag; or, perhaps worst of all, a coerced promotion from tortured to torturer?

One man she interviews, beaten, imprisoned, and widowed by the state (which would later rehabilitate him and, posthumously, his wife), loyally bequeaths his apartment to the atrophied Communist Party twenty years after the Soviet Union is dust.

*

Alexievich exercises her gifts invisibly; this is what the genre imposes. The sentences are not hers, the style and the characters—not hers. Her talent lies in the way people open up to her, but there is almost nothing in the books themselves to indicate how she achieves that. What makes people spill what they spill, things they’ve never spilled before? Her skill at extracting truths is so tremendous that the tellers themselves become ill at ease with what they turn out to know. Some of them sue her for defamation, even as they affirm that she quoted them accurately.

There are other aspects to her artistry, secrets buried in the outtakes. How does she decide what to keep and what to omit; what makes the final cut and what ends up on the cutting room floor; how to sequence sections and speakers, how to choreograph a book? The answers to these questions also lie outside the covers of her works.

Some ask whether what Svetlana Alexievich does is art. I know only that it is almost unbearably gripping and that the true stories she draws forth and presents have far more urgency than most of the fables or fictions now being written. Each time I close one of her books, I think: yes, her critics may well be right when they say that the Nobel Prize for Literature should not have been hers. Perhaps she should have gotten the Peace Prize.

*

In a remark that I came across long ago and cannot source, some literary critic, Edmund Wilson, let’s say (I choose him because he taught himself to read in Russian), gave three reasons why every intermediate-level Russian language student should plow through War and Peace in the original, start to finish. It is a valuable exercise, this critic said, because Tolstoy’s style, simple and clear, is accessible to someone who’s been working at Russian for just a few years; because the novel’s frequent interludes in “that refined French in which our grandfathers not only spoke but thought,” as Tolstoy has it very early in the book, provide the weary reader with a rest from the Russian parts; and because the book is so long that by the time the reader arrives at the end, her knowledge of Russian will be greatly improved. (Protracted stretches of Russian intercut with briefer ones of French, all of this going on for a long, long time, culminating at last in a greatly improved grasp of Russian. Why, it sounds like a highly compressed account of my own life.)

Perhaps the five volumes of Alexievich are my War and Peace, though some say they are not Russian (because she is Belarusian) and others that they are not literature. My Alexievich marathon is the latest stage in my trek toward the mysterious heart of Russian literature, a trip I embarked on some three decades ago, boundless optimism and persistence my only cargo. Russian literature hovers forever before me, a mirage on the horizon. For years on end, it seems to get no closer, and then from time to time it expands to fill half the sky.

My Alexievich marathon signals as well one phase in my twisting writing path. I chose my writing over hers—isn’t this what creative people are supposed to do, sacrificing whatever they must so as to clear space for their work? If there exists a map guiding this writing journey of mine—I imagine one of those antique charts fading out at the unexplored margins of the world, where, wreathed in flame and emitting puffs of smoke, dragons lounge and flick their tails—then here is a section of it, reader, unfolded before you now.

As the decades pass, the losses mount. No surprise there. Some version of this happens—doesn’t it?—to all of us who make it to midlife.

What has taken me by surprise is that in struggling to minimize the very heaviest losses—to save myself from going under, to swim ashore—I unwittingly called down further ones. To survive, or else to slow my decline—I’ll never know which—I chose the nine-to-five job and the little yellow pill, and in doing so, I sacrificed a treasure.

I had to live another ten years to find out exactly what I’d passed up. And if I’d said yes to the Midwestern publisher, agreed to translate the books, turned my back on the job, with its irresistible, indispensible remunerations and unavoidable humiliations? I would not have gotten the yellow pill, might not have been able to finish translating those books, not have lived to see where my labors led or to watch on YouTube as Svetlana delivered her acceptance speech.

This does little to assuage my regrets.

__________________________________

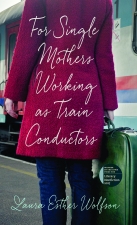

From For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors. Used with the permission of University of Iowa Press. Copyright © 2018 by Laura Esther Wolfson.

Laura Esther Wolfson

Laura Esther Wolfson’s writings have appeared in leading literary venues and garnered awards on both sides of the Atlantic. She holds an MFA from the New School and lives in New York City.