“I think I might have gone on drawing forever.” Annie Hartnett on Giving the Gift of Art

The Author of Unlikely Animals on Creating Connection Instead of Commodity

During the end of my MFA years, I asked one of my professors how to succeed as a writer in The Real World. He had two pieces of advice:

1. Before you leave [this incredibly cushy environment], start another book. Put the novel you are working on aside for a few weeks and prove you can write something else. He said he’d seen many students toil away at that first book, never get it published, and then give up on writing completely.

2. Read Lewis Hyde’s The Gift.

I dutifully started a new novel before I graduated, and it was reassuring, to be sure, to know I had another idea in the cooker. I also looked up The Gift, described as “A brilliant defense of the value of creativity and its importance in a culture increasingly governed by money and overrun with commodities.”

But I did not question the value of fiction. Nothing in the world was more valuable to me than a good story. So, I did not buy The Gift. I didn’t think I needed it. I needed an agent instead.

I was one of the lucky ones, and my first book, Rabbit Cake, was bought, eventually, following a healthy amount of rejection. Masie Cochran, an editor at Tin House, called my agent and said she wanted to buy it, “as long as she reworks the scene where the sleepwalking sister kills all the chickens.”

“No chickens shall be harmed,” I agreed.

And then, finally, only then, perhaps to celebrate, I bought and read The Gift.

Hyde’s book is a study of gift-giving and the relationship between an artist and the recipient of the artwork (a reader, in my case). Gifts are, Hyde says, an important way to create ties between strangers: a gifted cigarette, cookies for the new neighbors. When you buy something, on the other hand, no bond is created; the checkout person never thinks of me again. So, if people pay money for art, is it a commodity? Hyde argues that art functions more like a gift because of the emotions involved, the soul work the artist put into the art, and because art creates a connection between giver and receiver.

Art also is more like a gift than capital because art thrives when it moves. Gifts move; possessions are stagnant. Art moves through the artist first: creative inspiration arrives as a gift, which gives the artist the momentum to do the work (“talent” is another gift, not to mention the luxury of time). But once the work is done, if the artist holds onto his painting, doesn’t show it, doesn’t share it, keeps it in a closet for no one to see—the art stalls out and ceases to be a gift. Art must be given away to maintain its gift value, and the artist must fully nourish their creative spirit by sharing their art. It is not enough for the artist just to create without sharing, and if the gift isn’t shared, the artist will have a harder time creating something new. A reader must read the book in order to complete the gifting cycle and enliven the spirit of the writer.

I agreed with all this, knowing that sharing bits of my novel with my husband had enabled me to keep writing it. The sharing was fuel for the art. But, okay Lewis, one final question: if art is a gift, should the reader pay for the book? I paid for his book, didn’t I?

In the end, Hyde concludes that an artist can participate in the market exchange, but not too much. The gift of art can be ruined, Hyde said, if it becomes more of a market exchange than a gift one. There’s a spectrum. After that, I felt a little bit glad I had received a small advance for my first book.

When Rabbit Cake came out, I had a blast giving readings, prizing above all the gift of an audience’s attention and laughter. I loved signing books, writing someone a little love letter while they waited. These events all felt like a proper gift exchange, when the art is doing its job of bonding people who were previously strangers, leaving us friends.

Art must be given away to maintain its gift value, and the artist must fully nourish their creative spirit by sharing their art.

But I would also learn that there are ways that having a book in the world feels terrible, like carrying your brain around in a jar and asking people what they think of it. The feeling is worst at the times when people treat the book as a commodity they’ve paid for, rather than a gift I’ve offered them. If I opened a birthday present from my husband and announced: “I give this four-and-a-half stars,” I think he would be insulted, even though that’s a pretty good rating. And yet, people regularly spoke this way to me, taking the online rating system offline. “Four stars,” a stranger said to me at a bookstore event. “You should have gone further with the sister.”

Perhaps have her kill a bunch of chickens, I thought but didn’t say.

(To be clear, I don’t care what people write about my books on GoodReads or other review sites, that is not for me to know about, but it’s strange to say to my face!)

“Our book club gave it an 8 out of 10,” one woman said when I visited her home.

An ex-boyfriend texted me once that he bought my book because it was on sale on Kindle for $1.99. Can’t beat that price, he typed.

Free at the library, I texted back. Let me know if you read it. The gift, for me, is when a person reads it, not when they buy it. The attention to the art is the gift.

Hyde’s book was written and published in the 80s, before GoodReads, before email, before social media, before ex-boyfriends could text you. But he could see that treating art as a commodity was bad for the artist.

For a while after my first book came out, I couldn’t write, not at all. There was too much feedback in my head, the good and bad. Finally, I was able to tune it out by writing the next book for just one person, a bookseller I barely knew named Hannah Oliver Depp. She had told me: “I don’t know what’s wrong with your brain, but I loved your book.” That was the perfect reaction to me; it was everything I could have hoped for from a reader. She was the person I wanted to gift another book.

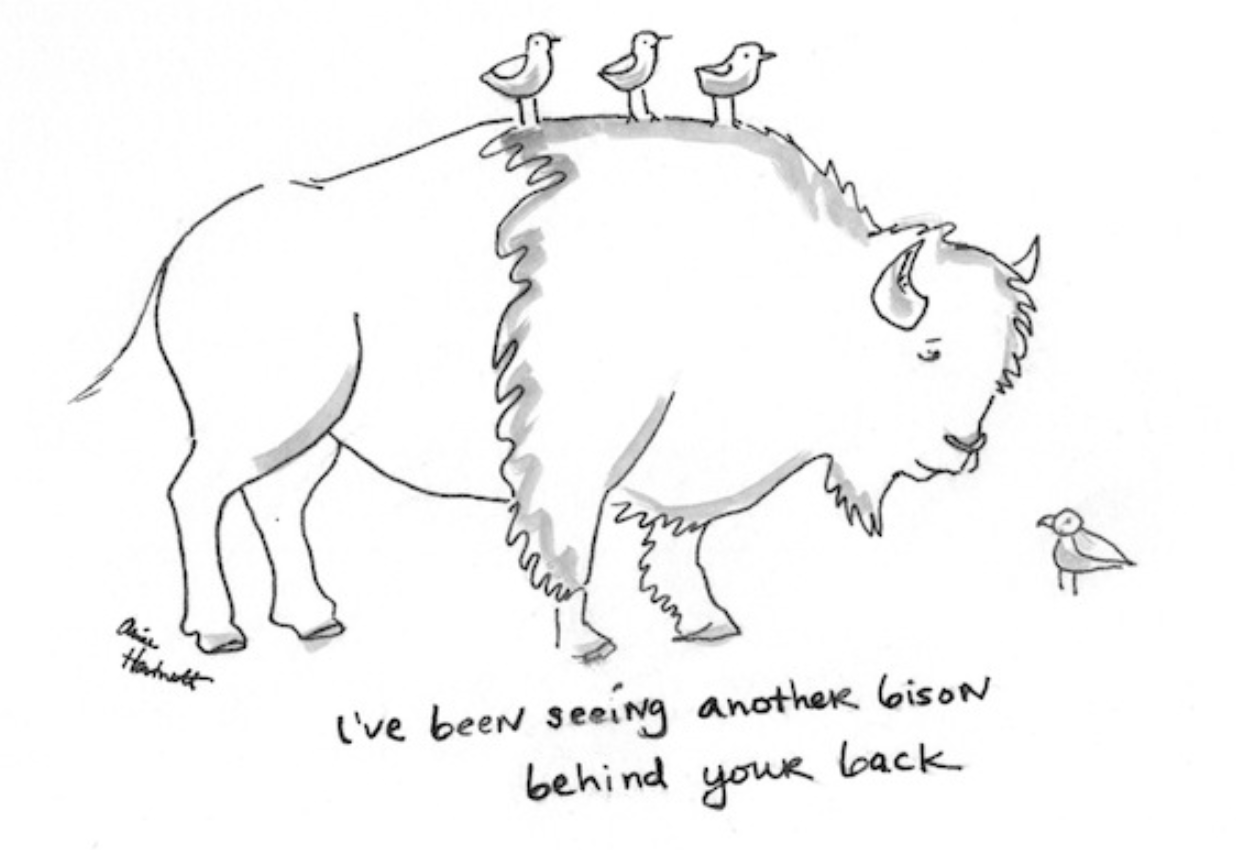

I’m now back in the promotion phase of book writing, and asking people to preorder your book feels even worse than asking people to buy it, since you’re asking people to shell out money now for a book they won’t be able to read for months. So, as I asked for preorders, I felt compelled to give people something in return. I can draw, I thought, and so I made the offer: Order Unlikely Animals from your local bookstore, and I’ll draw and mail you the animal of your choice. I said no pet portraits at first, but quickly changed my tune. People wanted pet portraits, especially of dogs who had recently died. I wanted to give them what I could.

My agent regularly reminded me that I was effectively losing money by making these drawings, paying for supplies and postage, but I don’t think I’ve ever been happier creatively. This gift exchange was so much more immediate than writing and more personal. People often framed the drawings immediately upon receipt, making me cry from feeling so appreciated. Two people said they were considering tattoos. I am an extremely social person, and I’ve been locked up in pandemic-motherhood, and for the first time in a long time, I was making new friends. I was chatting with strangers, hearing memories of dogs passed away; why a goose represents a memory of a grandmother, arguments between spouses on whether or not rhinos are mean. I drew a sloth riding a Peloton for author Taylor Harris (whose debut memoir This Boy We Made I promptly bought); a fox for a Pulitzer Prize winner, and yet another four-year-old asked for a meerkat (four-year-olds all love meerkats! The many mysteries of children). I drew a pony for my father’s old friend who, as a child, loved a Shetland named Georgie Porgie.

I made 350 drawings over the span of three months. I stopped six weeks before publication, but I think I might have gone on drawing forever, if I hadn’t gotten an idea for a third book, and suddenly and passionately wanted to work on that. Lewis Hyde would tell you this is how the gift of creativity works: giving your art away nourishes the spirit, and sparks a new idea, another gift.*

*I stopped drawing for 19 days, during which time I wrote this essay, worked on my new book, even watched a few movies. But the world grew darker during that time, and I felt I needed it again: the requests for a guinea pig wearing a beret, or the pictures of Ginger, the best cat ever. So, I decided I’d draw a little more, a little longer, and offered the drawings again for just a few more weeks. The gift wasn’t done with me yet.

__________________________________

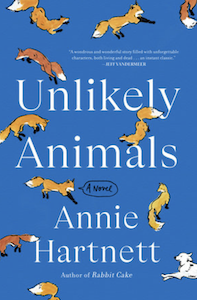

Unlikely Animals by Annie Hartnett is forthcoming April 2022 through Ballantine.

Annie Hartnett

Annie Hartnett is the author of Rabbit Cake, which was listed as one of Kirkus Reviews’s Best Books of 2017 and a finalist for the New England Book Award. She has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the Associates of the Boston Public Library. She studied philosophy at Hamilton College, has an MA from Middlebury College, and an MFA from the University of Alabama. When she began writing Unlikely Animals, she was living in the groundskeeper’s house in a cemetery. She now lives in a small town in Massachusetts with her husband, daughter, and darling border collie, Mr. Willie Nelson. Photo by Merissa Conley.