We were a very poor family and like all poor families knew who had what and how.

How you steal a book-size magazine or any book is much more difficult than most things you might shoplift. Books are a hard-to-hide size, heavy, prominent. A record you can slide between other records and into a bag. A magazine, same way. Clothes are easiest of all because they fit under your clothes. Casual secrecy is how you shoplift most things. Just be quick and sly: people are distracted and also mostly reluctant to bust you. But my technique for books took courage. This is what I did. I walked in reading a book while wearing my backpack. It was always a new book. Usually I had written my name across the pages opposite the spine, the fore edge, to make it as prominent as possible. I’d keep a pen in the book. Then I’d find the Paris Review or whatever. I’d find a few books, sit down in the aisles, read a bit. I’d write my name on the new Paris Review. I’d put the book I’d walked in with into my backpack and the other books back on the shelves, walk out reading the Paris Review. If stopped, which I was, more than once, I’d just say oh I came in with this. If they doubted me, which also happened a couple of times, I’d show them I had my name on all my books, which I did, even in grad school.

Once a friend of mine, Pierre Lamarche, now a phil professor at UVU in Utah, looked at the books in the office we shared and asked me, does your mom sew your name in your underwear too? He didn’t understand that I’d been using this technique to get my books for years. I used it through junior high school and high school and even in college bookstores. I used it in Half Price Books in Austin. Eventually I used a Sharpie because it was faster and more conspicuous, and I learned I could write my name, put it back on the shelf, and return to carry it out later. At Half Price Books they knew what I was up to and more than once told me, you can’t come in here with a book. But I continued.

When I was in junior high at Rideau Park School in Canada I used to take the bus downtown to a bookstore in the mall where I would steal my copy of the Paris Review. I read the whole thing back then, keeping it in my backpack, and then threw it away so that my mom wouldn’t ask me how I got it.

I’ve never published there, and a woman I was dating in New York—when we were winding down but not quite through with each other—she called me at my office and asked me if I had read the latest issue. I said yes I had, because by this time I was a subscriber and also had insisted that my university library carry a subscription. She said, that new story—did you read that one?—it’s brilliant. I knew the one she meant. I said yes I read that one and I felt like the author was still hiding something. She said no, that was why it was so good, it’s what every woman feels like. I said the narrator is a boy. She said yeah, but whatever, it’s a cover-up, it happened to the writer. I said yeah, that’s what I’m saying, something more happened that she didn’t tell us. She said you always think you know things about what the writer was thinking but nobody knows. Not even the writer. I said well, you’re the editor.

At this time I was also secret-drinking and the woman I was dating was my editor at a magazine. At last I can be honest about this relationship. She was young and seemed to have enormous sexual enthusiasm but we were both faking our interest in each other because we were so unhappy. She had told me she was in love with someone else, a friend of ours. I wanted only to believe that other possibilities were still before me, that I hadn’t already closed all the doors to future changes.

This was complicated because she was my editor and the man she loved was the editor of the Paris Review who used to be my editor. So at this time I was suspicious of editors.

Later, the writer of the story in question (who was an editor at a different magazine) interviewed me, and then we fell in love over Facebook and texts, and then we were married, and now we are parents together.

I still haven’t told the story I meant to tell. Before I became the writer and the professor who could tell his college library to subscribe to a magazine, but after high school and college, I owned some jewelry stores. And at that time I was addicted to cocaine and owned a Glock and tried to shoot myself in the mouth every morning. It was never a habit. It was a resolution, which I daily failed. It was the saddest and most self-loathing time in my fifty-four years, including my childhood, which was, as the song says, “hell. Hell is for children.” Not to be maudlin. But at that time I was also taking speed in the afternoons and evenings so that I could stay awake long enough, after I got off at my jewelry store around 7 p.m., to go check on the wine bar I owned on McKinney in Dallas. And between the jewelry store and the wine bar, sometimes I’d stop at home to write. I wrote more than a hundred stories at this time, often three or four in a night. That was twenty-three years ago, and I still want to tell the story I want to tell.

__________________________________

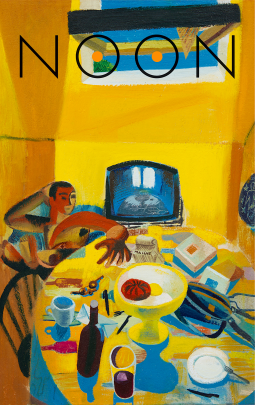

“I Still Haven’t Told The Story I Meant to Tell” appears in the 2022 edition of the literary annual NOON, which will be published this month.