I Made a Book of Erasure Poems Out of Stephen King’s Misery

As Sarah J. Sloat Writes, There Are Just Too Many Good Nouns

Until I began working on the poems that would become Hotel Almighty, the last thing I thought I’d be was an erasure poet. I wasn’t even sure I was a poet until I reached my 30s. I put it off for a long time because though I’d always loved poetry, I thought poetry belonged to the gods. Well, it belongs to the gods, of course, as an offering.

*

My attraction to erasure poetry starts with an attraction to found things in general. If someone drops a shopping list in the supermarket, I pick it up and read it. I draw mental lines between the items, connect the lime to the avocado, the toilet paper to our current panic.

When I moved to Barcelona from Germany three years ago, one of the first things that hit me was how many children there were. I began finding children’s drawings in the streets. On my street! And lost math problems and abandoned music notes and those notes girls pass back and forth in the classroom.

There’s an enchantment in the found, as if something had been waiting for you. I feel that way with found poetry.

*

Nevertheless, I came to erasure poetry, a kind of found poetry, casually and without commitment. In late 2016, some poets were organizing a poem-a-day project, in which each participant would be assigned a different Stephen King book as a source text. I was game. I asked if I could have The Shining since I owned a copy. But someone had dibs on that and I got Misery, which I’d never read. The project lasted a month, but I spent the next three years mining Misery.

*

I didn’t begin with a blueprint. A couple of initial poems were political, as erasure poetry often is. And it was the autumn of 2016. But then I let the poems go where they would.

*

I found Misery a rich place to hunt for poems. My experience with it, and subsequently with other books, taught me a lot about what makes a good source text, at least for me. Rule #1 is steer clear of texts you love. You will always come up short. Rule #2 is avoid texts about abstract concepts that are thin on good nouns. They won’t engage the poet or the reader.

*

Fortunately, Misery is full of happenings and tactile memories. It takes place largely inside one room in a secluded mountain home. Sometimes the sun melts the snow. Sometimes a car drives by. There is a wheelchair and creaky floors. There are ceramic figurines and a massive manual typewriter and blister packs of painkillers. The concrete items gave me something to latch onto, to carry in different directions and make metaphors of.

I wasn’t necessarily trying to subvert Misery. I wanted to break out of it.Stephen King is a dynamic storyteller, big on strong nouns and verbs. Sure, Misery is “horror,” but not woo-woo horror. It’s bad breath and jello-for-dessert horror, with a splash of maniac. It seemed a lucky accident to have it.

*

Whatever the source, a significant challenge of erasure poetry is its limitations. You receive a finite word bank. And, in the approach I used for these poems, you need the right words in the right order. You can bend things a little, hide the “s” in “takes” if it’s “take” you need. You can turn “spillage” into “ill” or “age.” But that word or phrase that you’re sure would shoot your poem into the stratosphere isn’t going to materialize magically. There’s a good dose of chance in it. If a suitable word isn’t there, you need to surrender that particular fight.

It’s important to be open to possibility, ease your grip on your specific hopes or expectations. Abandon a potential start to a poem if it leads to a dead end. Turn instead to the good end and see if there’s another way to get there—just as you would when writing a conventional poem. Erasure poetry is poetry.

*

As a starting point I limited each poem to one page and left it there, making the page the frame. Beyond that, initially I didn’t plan to give the poems any special visual element.

Erasure poetry often is visual, though. Most people are familiar with blackout poetry, a form of erasure, which sometimes resembles a redacted letter. This works well especially when the poet is subverting the source text. I wasn’t necessarily trying to subvert Misery. I wanted to break out of it.

*

The idea for incorporating visuals grew out of the blank pages, which offered themselves up as small experimental spaces. After trying various approaches I decided the visuals should make the poem easier to follow rather than becoming distractions. And I wanted them to be inviting, to ask the reader to step inside the page, as one would step inside a house or landscape. Lastly, I wanted to do it by hand, giving the pages texture rather than altering them digitally.

*

I avoided connecting the visuals directly to the text, leaving room for the reader to make their own associations. I used images from a variety of sources—vintage photographs, magazine clippings, a geometry book, thread, confetti, teardrops cut from a wine label.

*

I had stacks of material to choose from but I was constrained by the miniature canvas, which shrinks as the poem grows. In [I’m going up ace…], for example, the little scene had to squeeze between lines.

I let the page languish half-finished at the corner of my desk for days, then weeks.In a few pieces, I cut away the excess text with an x-acto knife and laid the page over the visual elements. Essentially, in those cases, the collage lies behind the page rather than on top of it. This technique was used to create the cover as well.

*

One of the last poems I worked on was about a word that breaks a “queer silence.” To make it, I blanked out the unwanted text with a white pastel crayon and assembled a couple elements at the bottom of the page. The text worked but the collage never seemed to come off right.

Maybe I should have made the page blue or red instead of white. Unfortunately my process didn’t allow me un-erase most decisions. Unlike a conventional poem, I couldn’t banish an offending line or change a color once it was set down.

I let the page languish half-finished at the corner of my desk for days, then weeks, never satisfied with whatever I planted there. A snake. A yellow square. A tombstone.

*

Last winter before tying up what would be included in Hotel Almighty, I was at a flea market where at the end of the day a vendor was giving away small items he didn’t want to schlepp home. I was waiting for my daughter to finish buying something at a stall nearby so I poked around. Bad photos, a toothpick holder, old flip-flops.

And there was the missing piece for my poem about the broken silence: a miniature playing card with three suns blazing red on black. As if it had been waiting for me.

__________________________________

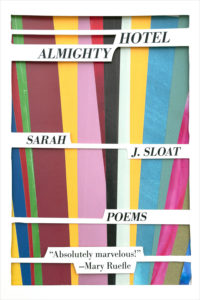

Sarah J. Sloat’s Hotel Almighty is available now from Sarabande Books.