Eve

Today is my grand finale at Wellesley High School. I didn’t think of it as a big deal until Paige stopped in on her run this morning to see how I was feeling. She seemed surprised to find me unfazed. I want to feel sentimental—I do—but my emotions peaced out with my mother. Now I’m just water and bones.

The hall is packed with kids emptying out lockers. Lindsey and I shared since mine was in a clutch spot by the stairs and vending machines, but she cleared her stuff out days ago, probably to avoid us doing it at the same time. This won’t take long. I rip down the pictures we hung like wallpaper on the back wall and shove the spare makeup bag in my backpack, embarrassed I used to refer to an unexpected pimple as a 911. Everything else goes from my locker to the trash.

The inside of the metal door is covered with penciled graffiti where Lindsey and I passed gossip between classes. I’m supposed to erase it so I don’t start next year with detention, but they can’t exactly track me down in New Hampshire. I heard Jake say you have a fine ass, I wrote, starting the exchange in September. OMG—he’s such a drooler, Lindsey replied. And on it goes, until the day before Good Friday. No hot gossip after that unless I was the butt of it. I notice a new message across the bottom of the door: I so hope you find a way to be okay. That’s it. A simple wish from my old best friend. It doesn’t bring a single tear. I’ve become a freaking zombie.

I consider how different this day would be if my mother were alive. Everyone’s headed to Noel’s because his parents totally don’t give a shit what happens there. I’d be passing twenty bucks to Katy whose big brother is hooking everyone up with beer for a small profit, and John would be working on cover stories so we could both spend the night. Instead, I’ll walk out alone and go home to an empty house. My father won’t realize today was the last day of school until I don’t go back tomorrow.

I turned in a poem for my creative-writing final. Picking it up stands between me and the end of junior year. The assignment was to write a short story, but Mrs. Ludwick gave me an A for these four lines.

SILENCE SAID

I have no idea where to start

How to repair a broken heart?

Where a laugh means more than the mere amused

It means a tear has been refused.

The grade was probably because she felt sorry for me, but still. At the top of the page, she included a handwritten note: You seem to have something to say. You should try writing without the constraint of rhyming. I hold the paper up, pretending the message is longer than it is to avoid eye contact with everyone. The cover-up is probably unnecessary; there isn’t exactly a line of people looking to chat it up. Everyone’s sympathy ran out when my mourning came at the cost of the soccer team’s starting lineup next fall: John’s DUI got him benched the first five games.

The seniors are all hugging, shaking their heads at how fast it went. The juniors, my classmates, are running around in a tizzy announcing that the Class of 2016 has officially taken over. “Get ready to be hazed,” Jake taunts, knocking the baseball cap off a kid I don’t know. Kara shrieks the words as if over and over about some freshman who made a pass at her. She’s clearly started drinking already, which is bold even for Kara. They all sound like assholes. When the big metal door shuts behind me, I’m numb.

I once saw an Ellen DeGeneres where kids cut themselves with knives. There were pictures and video clips, but I still didn’t buy it. I figured if they were really cutting themselves it was to get on Ellen and not, as they claimed, for the pleasure of feeling something, anything. Now I’m not as sure. I walk to the car, letting my backpack dangle from my elbow and smash uncomfortably into my legs with each step. It hurts, but it’s better than nothing. Mom sometimes carried pots off the stove with her bare hands. She claimed her skin was callused from years of cooking, but maybe the burn made her feel alive. I can practically hear her denying it, begging me to take better care of myself. It’s a new low: I’m so desperate for affection I’m inventing conversations with a dead person. I pinch my arm to distract me. Indifference is scarier than pain. It makes you think there’s no point being here.

* * * *

I stupidly left my writing final on the kitchen counter and when I come down for dinner, Dad has it in his hand. “Wow, Eve. This is poignant.”

I refuse to turn it into a whole big talk, so I say nothing.

He squints his eyes like he’s afraid of the words that want to come out of his mouth. “I’ve been thinking you . . . well, you and I, should go to therapy.” I stare at him. “Not together or anything. On our own.”

I laugh. He doesn’t. “Does the poem worry you?”

“Not at all. The poem is fine. Beautiful. It’s the note from your teacher. She’s right. You probably have a lot to say. I know I do. But who am I going to say it to? You’re the only one who can relate, and I don’t want to be a burden.” He shakes his head to show that’s not what he meant. “Not that you’d be a burden to me. You can talk to me anytime. I-I hope you know that.” He’s flustered. “God, my sales pitch stinks, but will you go? To counseling?” He extends his arms in a whaddayasay gesture.

“Whatever.”

“Whatever as in you’ll go?” he confirms, unable to hide his shock.

“Sure.”

I play it cool, but the truth is, it sounds like a damn good idea. I’m not completely losing it, but my masochist moment this afternoon was pretty close. And a couple nights ago I woke up obsessing over an old picture of my mom and Gram cooking. I needed to find it. Right then. It felt enormously important. I got up and emptied an entire bin of prints from the guest-room closet, flipping through each one, as if this random photo held the secret to their deaths, as if this random photo would bring them both back to life. Eventually sunlight filtered through the window, snapping me out of it. Hours had passed. I was ankle deep in photos, sweaty and tired, but mostly confused. I couldn’t remember why I wanted to see the stupid thing in the first place. When I calmed down, I remembered the picture was in a frame at Aunt Meg’s. I don’t know how I’d forgotten (or how I suddenly remembered). The whole thing was flat-out psycho.

Dad was expecting a fight. He stands there, holding the counter as if he might need it for protection. When he processes that he won, that I’ll go to counseling, he pulls out a copy of an email from his briefcase.

“Here’s a list of all the local therapists covered by our insurance.”

This went from casual idea to concrete plan mighty fast. “God, Dad. How long have you been, like, scheming for this?” He confesses it’s been a few weeks. I arch my eyebrows. “And . . . you never said anything . . . why?”

“I booked my appointment already, but I’ve been waiting for the right time to ask you.” He stops there but then pushes on. “Admit it, Eve, you’re temperamental. I never know how you’ll react to stuff.”

It’s true, and he called me out the way my mother would have, so I pick up my cell and book an appointment with the first female shrink on the list. I love shocking my dad. It’s one of my few remaining kicks.

That night, to prepare for therapy, I write in my new journal for the first time. I only get out fifteen words:

June 15, 2015

There are so many things I dare not say I have quietly stopped being me.

I stare at the sentence for a long time, questioning what it is I want to say. Who was I, really, before my mom died? I was a self-absorbed, materialistic, conceited, naïve child. So maybe what I want to say is simply that I’m sorry. Only the person I want to say it to is gone.

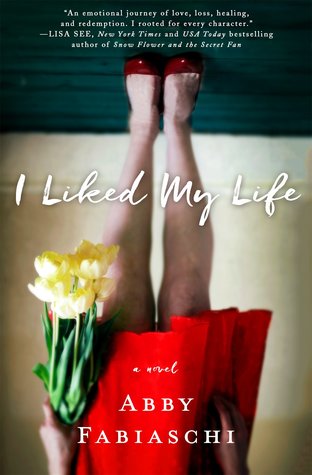

From I LIKED MY LIFE. Used with permission of St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 2017 by Abby Fabiaschi.