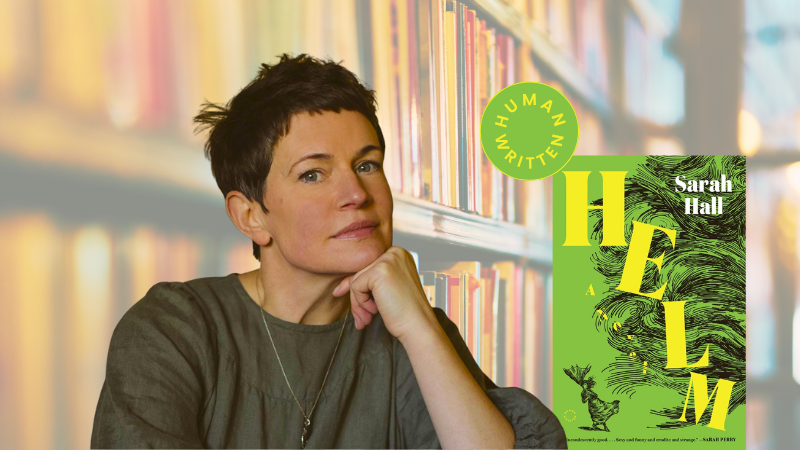

“Human Written.” Why Sarah Hall Put a Maker’s Mark on Her New Novel

Sarah Hall on Authenticity, AI, and Big Tech’s Creative Larceny

Helm is my tenth work of fiction, and the front jacket of the novel will feature a Human-Written maker’s mark—one of the first in the book trade.

I’m not exaggerating when I say this novel took decades to write. Like most fiction, it’s made up of experiences, imagination, ideas, memories, emotions, speculation, knowledge and research. I had to live a lot of life in order to write it.

The book is about a unique life-force, the only named wind in Britain—a hurricane strength storm that occurs in the Eden valley where I’m from. It’s about humans interacting with landscapes, climate systems and each other. The book was created using a biological, sensual craft, as well as a cerebral one. As I said to my publisher when we talked about a Human-Written label—it has blood on the page, metaphorically and literally.

What’s going on is creative larceny at scale.

While I was finishing the novel, conversations around copyright, AI systems training and the un-licensed use of fiction were hotting up. It turns out most of my books have been consumed by LibGen for those purposes—with no consent and no compensation—as have many works by many writers.

What’s going on is creative larceny at scale. At the same time endorsements of AI-written fiction began occurring by my peers, those with skin in the game. In the not too-distant future, or maybe just around the corner, AI might be able to issue a saleable version of Helm. In under three minutes. Without ever having felt the power of the Helm wind. What does this mean?

Sustaining a career as a writer—one who is trying to make original, beautiful, empathic art—is challenging enough without this prospect. The creative industries are desperately wondering how to respond to these rapid technological developments.

In the US, the Authors Guild and a group of writers have filed a class-action suit against OpenAI, and the Guild has produced its own version of a maker’s mark. In the UK, the Society of Authors has been fiercely advocating for stronger measures to protect writers, and it is supporting individual initiatives such as mine that aim to raise public awareness. It is planning to launch a Human-Authored registry system later this year, in collaboration with publishers.

Though the UK’s creative industries are valued at approximately £124 billion to the economy, our government is seemingly toothless on the matter of safeguards for the arts, refusing the House of Lords amendment to the Data (Use and Access) Bill which would have protected creators by forcing tech companies to be transparent about their use of copyright material in LLM training. The bill passed in June without media attention, while bombs were dropping on Iran. Resistance to runaway-AI by organisations such as the Society of Authors becomes more and more vital. The principle is about art, its value, accreditation and ownership, not “data.”

Labels matter. They convey contents, provenance, culture, ethics and authenticity.

Of course, it’s hard to get ahead of radical progress where machine development is concerned. Textile workers, carpenters and musicians didn’t or couldn’t. The threat of more efficient, devaluing production models to the livelihoods of artisans is historically clear.

But literary consumers, book buyers, of which I’m one, may soon have a two-tier choice. Invest in fiction written by humans and so support human creativity, vocations, and organic economies? Or get automated stories cheaper (no doubt) via AI and support—what, who, which tech company, ultimately? And this is not to mention the resources consumption of AI, a cost which isn’t immediately quantifiable or made clear.

To their credit, when I raised the issue of having a maker’s mark on the jacket of Helm, Faber & Faber agreed. They understood exactly what I wanted to do and why. And when I told my US publisher, Mariner, about the decision, they enthusiastically followed suit. Labels matter. They convey contents, provenance, culture, ethics and authenticity.

I’m not against AI. It is useful and empowering in lots of ways: admin, teaching aids, medical research. It may one day innovate literature beyond human scope. But I am from a county of humpbacked bridges carved with stonemasons’ signature marks and distinctive cottage industries. Cumbria has a history of dispersed and communitarian makers, skilled and specialist producers—we know full well what happens when power is concentrated away from small independent outfits into the hands of bigger businesses, impersonal industries and profiteers.

From those first hand-scrawled sentences to the final dementing rearrangement of commas, my books are very humanly made: proudly, imperfectly, with difficulty and with tremendous care.

If Northern Romanticism means anything to me it’s not the aesthetics, it’s the radical critique of power structures and social justice, the hope for positive human outcomes. The issue isn’t about any new tools we might use, it’s about a damaging shift in the balance of trade.

From those first hand-scrawled sentences to the final dementing rearrangement of commas, my books are very humanly made: proudly, imperfectly, with difficulty and with tremendous care. They are felt as they are composed, painfully, joyously, cellularly—and they are designed for other biological beings to experience, to connect with, to be animated, provoked and moved by.

Of all my books, Helm has been so hard and so lovingly written. It’s big and intricate, political and personal, it’s playful, fearful, awed; it is wind-swept because I have been. It’s not only about a unique aerial phenomenon and meteorology, it’s about thousands of years’ worth of human endeavor and ecology. Our place in the natural world and nature’s place within us. Damn right I want that label on this book. And I hope other writers—who work so hard and purposefully to craft what machines cannot—will do the same.

__________________________________

Helm by Sarah Hall is available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Sarah Hall

Sarah Hall was born in Cumbria. She is the prizewinning author of six novels and three short story collections. She is a recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters E. M. Forster Award, Edge Hill Short Story Prize, among others, and the only person ever to win the BBC National Short Story Award twice.