Hugh Bonneville on His Illustrious Downton Abbey Castmate, Maggie Smith

“We all knew Highclere Castle was the lead character. And we all knew that Maggie Smith ran a pretty close second.”

None of us involved in Downton Abbey have ever taken its success for granted, but there is no doubt that as three seasons turned into six and then a movie, it became as familiar and comfortable as a favorite sweater. When it came to the second film, however, after everything all of us had been through during the pandemic—isolation, fear, loss—I looked on each day of the job with renewed appreciation.

Coming up the drive and glimpsing the tower of Highclere Castle had always given me goosebumps, but the feeling seemed more potent this time round, knowing that the audience for the film we were making would be more than ready for a slice of big-hearted, escapist entertainment.

We were fortunate to make the film at all. The start date had been pushed back because of the lockdowns in 2020. We were finally scheduled to shoot in the spring of 2021, most of the cast being able to commit because there wasn’t exactly a lot of work around. The idea had been to film the French scenes first, while Michelle Dockery finished a Netflix project. Also, the crickets would be less noisy earlier in the year. However, because of Covid it looked increasingly likely that filming on French soil was going to be impossible.

I was as intimidated and intrigued by her on my last day of shooting with her as I was on my first.

One afternoon in February executive producer Gareth Neame phoned the production designer Donal Woods to say he was probably going to have to pull the plug on the film because France was simply too much of a gamble. Donal sought a few days’ grace while he and location manager Sparky Ellis put their heads together in an attempt to find a solution. Working round the clock, they drew up a list of locations in the UK that could feasibly double for the scenes set in the South of France.

A house at Longniddry outside Edinburgh had an interior that could pass for the entrance hall of the villa near Toulon. Manderston House in the Scottish Borders could be bleached white thanks to CGI and pretend to be the exterior. Its kitchens could get away with being called French. Trebah Gardens near Falmouth might work for Tom and Lucy’s seaside dip. Chilly, though. There were tropical gardens in Bournemouth, or the Italian gardens at Hever Castle in Kent; Gunnersbury Park in Acton could provide a dining room, as could Twickenham Town Hall, would you believe. As for the streets of a charming French fishing village, well, they would have to be green screen. Talk about an amalgam. But it could work, just about. The ideas were presented to Focus Features, who agreed that if the worst came to the worst Plan Z would be put into operation. The film could go ahead.

Downton Abbey was always billed as an ensemble show, as a cast we won three Screen Actor Guild Awards for being so. But we all knew that Highclere Castle was really the lead character. And we all knew that Maggie Smith ran a pretty close second. When I was first offered the role of Robert Crawley I asked Gareth Neame who they had in mind to play Violet. Had I been drinking tea at the time I would have splurted it out when he answered, “Maggie Smith.”

“Good luck with that,” I laughed, “She’ll never do it.” She was in her late seventies when we started the television series and we shot the second film more than a decade later. So, do the math, as they say. A pretty remarkable age to be working in any profession. I was as intimidated and intrigued by her on my last day of shooting with her as I was on my first. Her reputation preceded her, of course. A living legend. Famously waspish, razor-sharp intelligence and utterly instinctive comic timing, with the ability to turn to pathos and even to deep emotion in a heartbeat.

My first proper scene with her was in the drawing room at Highclere. Electric lights have been installed and the stage direction indicated that Violet shields her face for a moment against the glare. “It’s like being on stage at The Gaiety.” On the day, Maggie used her fan, flicking it up as a screen against the new-fangled illumination but she kept it there for what seemed like ages, ramming home the point of her character’s authority, her distrust and distaste for electricity as well as sustaining a comedic beat long after anyone else would dare. In the theatre it would have received a laugh that rose and fell and then rose again with the sheer audacity of the actor’s bravura. At least, that’s how I read it. I was in awe. And I remained that way for more than ten years.

She could be beady, sure, and laser-like in her put-downs. If the script supervisor approached after a fumbled take she might put her hands up as a shield of defense and waft her away, or mutter, “Oh gawd, ’ere she comes.” She would test each new director, too. On their first day she might suddenly find a problem with the motivation for a line, or question why she should sit here and not there. If the director came back with a clear, confident answer then she would be, if not putty in their hands, then certainly agreeable. Show weakness or doubt and she would eat them for breakfast. There were good Maggie days and not so good ones. The production team learned not to call her first thing, filming her in the middle of the day and letting her loyal stand-in Ros Rosenberg read in dialogue for the shots when she was off camera at the end of a long afternoon. Gradually a balance was struck and the best Maggie was the one that was captured on screen.

A balance was struck and the best Maggie was the one that was captured on screen.

She had three exits, really, from the world of Downton Abbey. To be honest, I thought Violet would die between films and that we would open the second movie with her funeral, because Maggie always said each outing was her last. In fact, she often seemed happiest on her last day of shooting each season. However, while her unflappable agent, Paul Lyon Maris, would reassure her that there was indeed no need to do it all over again, nevertheless somehow she was always there at the next readthrough.

I think it was Alistair Bruce, our stalwart historical adviser, who did some numbers on the back of an envelope and calculated that over the years we had spent the equivalent of something like three months, twenty-four hours a day, filming in the dining room at Highclere Castle. So Maggie’s final day on that particular set was a significant one for all of us. To while away the time between set-ups, on the occasions when leaving the room to relax off-set was more trouble than it was worth, we would chat or sometimes play games. Wink murder was a favorite. If there were, say, eight of us at the table, eight small bits of paper would be folded and placed in one of the silver mustard pots. This would be passed round for each player to extract one of the pieces.

However, one of them would be marked with a cross, denoting the murderer. With the game afoot the challenge was to carry on chatting and for the murderer to wink at their intended victim without the wink being spotted by anyone else. The victim would then choose their moment to die, either elaborately, perhaps by swooning off their chair and collapsing onto a grip who was trying to lay some track, or maybe by plunging face down into an imaginary bowl of trifle. One by one people would keel over, those left alive knowing their days were numbered but also having a better chance of deducing who the murderer was and pointing an accusing finger, thereby saving their skin. Look, I know it wasn’t the most productive use of the endless chunks of ten-minute gaps we contended with but it passed the time.

For the first time in the decade and more that she had played my mother, Maggie Smith reached out, took my hand in hers and gave it a gentle squeeze.

After Maggie’s final shot in the dining room director Simon Curtis announced the fact that this had been her last meal and Elizabeth McGovern presented her with a silver mustard pot as a memento. Her final appearance as the Dowager Countess was a tiny moment in the hall, watching the film within the film. I wasn’t there for that but her penultimate farewell was obviously the most significant, her death scene. Inevitably, it took all day and there were continuity issues to do with pillows being too high, too low but there wasn’t the sense of irritation that often crept into such scenes when minor details became editing problems. Everyone sensed this was a different, special day.

As we rehearsed, Maggie frail in bed, the rest of us gathered round respectfully, I couldn’t help but whizz through my memory bank of moments I had witnessed, not just from our show but from her career. The film and television performances, like Desdemona to Olivier’s Othello, The Pride of Miss Jean Brodie, California Suite, Room with a View, Talking Heads, Gosford Park, Harry Potter; stage performances like Lettice and Lovage, Three Tall Women and The Lady in the Van. I wished at that moment that I had seen her perform with her first husband Robert Stephens (he was an astonishing Falstaff in the main house at Stratford when I was performing next door in The Swan) in Private Lives or The Recruiting Officer. Above all I wished I had seen her in revue with Kenneth Williams. I could picture them gossiping in the dressing room before the show, sending people up, the air crackling with camp laughter and dagger-sharp derision.

Early on in filming season one of Downton Abbey, knowing their affection for each other and in an attempt to break the ice, I asked her about her friendship with the comic actor and famously acid wit. She immediately turned her head to one side and looked down, putting her hand up defensively. “I can’t,” she said, “I miss him so much.” I had evidently touched a nerve. I dropped the topic and never brought it up again.

Some years later a friend of mine rang to say he was going to meet Maggie at a dinner party and asked if I had any tips. “Well, you both love Wimbledon,” I said, “but don’t mention Kenneth Williams.” A few days later I called my pal and asked how the dinner had gone. “Oh, we got on famously. Great tip about Wimbledon, thank you. We talked tennis for ages. And there were brilliant stories about Kenneth Williams.” Good days and bad days, I guess.

Having run the lines of her death scene we began to rehearse. The kaleidoscope of all these memories flickered across my mind as the Dowager Countess took in first her cousin, played by Imelda Staunton, then her grandchildren (Michelle Dockery and Laura Carmichael) and then, as she turned her head towards me, her screen son, she did something I don’t think she had done in the entire series. For the first time in the decade and more that she had played my mother, Maggie Smith reached out, took my hand in hers and gave it a gentle squeeze. From then on, No Acting Required.

__________________________________

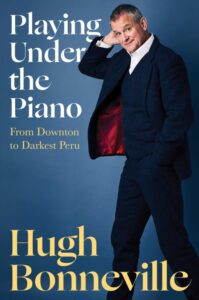

Excerpted from Playing Under the Piano: From Downton to Darkest Peru by Hugh Bonneville. Copyright © 2022. Available from Other Press.

Hugh Bonneville

Hugh Bonneville was a member of the National Youth Theatre of Great Britain and made his professional acting debut at the Open Air Theatre, Regent’s Park, in 1986. He joined the Royal National Theatre in 1987 and the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1991, where his roles included Laertes, opposite Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet. He is perhaps best known for playing Mr Brown in the Paddington movies and Robert Crawley in the ITV/PBS series Downton Abbey. Over its six seasons and two movies, Downton Abbey won dozens of awards worldwide, Bonneville receiving a Golden Globe nomination and two Emmy nominations for his performance. He lives in West Sussex, England, with his wife, Lulu Williams, and their son, Felix.