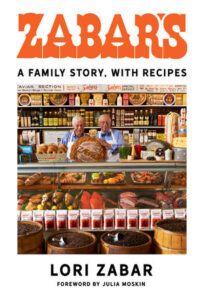

How Zabar’s Grew from a Modest Business to a Culinary Icon

Lori Zabar on a Pivotal Point in the History of a New York Landmark

As the 1960s began, the goods sold at Zabar’s were simple, traditional, and pretty much what my grandfather had been stocking in the 1940s. This was what the public wanted to buy, and Saul Zabar had been happy to spend his first decade of being in charge not innovating but simply trying hard to maintain the formidable standards that had been established by his father, Louis.

Running from one store to another was particularly grueling. Saul wanted to do one thing and do it well, and so as the lease on each of the storefronts came up for renewal (in one case, a fire caused severe damage), my uncle would let the store go, against my father’s objections—none of which really carried all that much weight with Saul. Although he was still a co-owner and assisting his brother as much as he could, my father was working full-time as an attorney and wasn’t willing to give that up to keep all of the stores going.

By the early 1960s, Saul was focusing his energies on one store: Zabar’s on Eightieth Street and Broadway. And now he had the time to do something he had been thinking about: adding new offerings to the old classics. Business administration may not have been his forte, but my uncle did have a sense that the gastronomic times were changing and that what his customers wanted was about to change, too.

Saul had no intention of altering the traditional appetizing and delicatessen that Zabar’s was known for. He simply added other gourmet items, many of them previously unavailable in the United States. He knew, for example, that his customers would enjoy high-quality bread to go with their smoked fish, so he began to stock a diverse collection of artisanal breads.

While most Americans were eating packaged Wonder Bread, Zabar’s offered twenty-five varieties of freshly baked bread—many of them whole grain or prepared without preservatives—that were made by small bakeries in the Bronx, Brooklyn, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. Zabar’s now sold French bread by the foot, flourless soy loaves, black Russian rye bread, German pumpernickel, and Polish rye bread. And, of course, different varieties of bagels and bialys.

Saul’s timing was perfect. An increasing number of Americans were beginning to travel to Europe as commercial transatlantic flights became more available, and when those people returned, they wanted to buy the foods they’d been introduced to overseas. And so Saul began to import a range of condiments—all kinds of oils, vinegars, mustards, honeys, and spices—from England, France, Ireland, Italy, Australia, and the Netherlands.

Saul had another reason for all this updating: he was hoping to sell Zabar’s and wanted to make the package as attractive as possible to potential buyers. He had given running the store his best shot, but despite the enticements of the expanded gourmet offerings, the profit margins were extremely narrow and expenses were still higher than income: Zabar’s was losing $200,000 a year.

Stressed by a divorce from Rosalie and ready for a life change, in 1961, Saul put Zabar’s on the market for $565,000. No buyers appeared, and there was nothing for Saul to do but carry on. But my uncle and my father realized that they could not keep Zabar’s going by themselves. So they appealed to Murray Klein, who had left their employ in 1957, to come back and help them turn the business around.

“If I walk out onto Zabar’s floor and I can see my shoes, it’s not busy enough.”

Murray had lived a harsh and tumultuous life. He was born in 1923 in Ukraine, near the Romanian border. World War II turned his world upside down. While he was a teenager attending a trade school in the Soviet Union, his parents and five siblings were sent to Nazi concentration camps, where they all perished. Because he had destroyed his identity papers, Murray was sent to a Soviet labor camp in Siberia.

Once there, he pretended to be ill, was sent to a hospital, and then made his escape. Ever an entrepreneur, Murray survived by selling bread on the black market in Siberia, until the threat of arrest for his illegal activities spurred an escape to Tashkent, where he remained until the end of the war. His next stop was a displaced persons camp in Rome, which had been set up in the then vacant film studio Cinecittà. There he joined the Irgun, the underground Jewish paramilitary organization, and helped smuggle arms from Europe to the Jews who were battling the British army in Mandatory Palestine.

Those activities led to his arrest and imprisonment by the British, but, once again, Murray found a way out, this time by staging a hunger strike that led to his release. Eventually, after Murray had endured roughly a decade of war and displacement, his cousin Aaron Klein found his name on a Red Cross list of war refugees and sponsored his immigration to America in 1950. Shortly after his arrival, he began working for the Zabars, first as a delivery and stock man and eventually as manager of one of the Broadway stores. He left in 1957 to run his own businesses, including a hardware store.

Saul and Stanley succeeded in getting Murray to agree to return to Zabar’s, where he was put in charge of the day-to-day operations, opening up the store every morning at 6:00 am. Three years later, he became a full one-third partner. A stocky, balding man with close-cropped graying hair, heavy-lidded green eyes, and a thick Russian Yiddish accent, Murray often sardonically referred to himself as a “peasant,” or as one of the “proletariat,” in contrast to the Zabars, whom he called “Jewish royalty.”

But, ultimately, it was working-class Murray who rescued Zabar’s from financial ruin and transformed the store into what it is today. He was a retail savant with a talent for both buying and selling food and appliances at the lowest possible prices. If the price of a product rose to too high a level, he dropped the item, even when it was in demand. Instead of creating a spare, elegant, and luxurious atmosphere, Murray stocked the store to its limits, hanging pots and pans, strings of garlic, salamis, and tea kettles from the ceiling, to create the sense of a chaotic yet exciting food bazaar. “If I walk out onto Zabar’s floor and I can see my shoes,” he would say, “it’s not busy enough.”

Actors, musicians, and intellectuals who lived and worked nearby, as well as neighborhood residents, congregated at Zabar’s on the weekends to socialize while stocking up for Saturday and Sunday brunch.

Saul’s prescient expansion into imported and artisanal offerings, combined with Murray’s astute management and salesmanship, occurred at a pivotal time in food history, keeping Zabar’s ahead of the curve during a time in which Americans’ taste in food was undergoing a revolutionary change. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy sparked a national interest in sophisticated French cuisine by hiring the French chef René Verdon for the White House kitchen in 1961.

Perhaps the most influential event in the growing fascination with French food was the 1963 debut of Julia Child’s televised cooking show, The French Chef. My immediate family had never been to France (they’d actually never been anywhere in Europe), and The French Chef was a groundbreaking introduction to a new and exciting cuisine and culture. Inspired by the series, my mother took a break from chicken baked in mushroom soup and tackled complicated recipes like beef Wellington from Julia Child’s cookbook Mastering the Art of French Cooking, which had been published to considerable acclaim in 1961.

My mother and my aunt Carole, Saul’s second wife, took cooking lessons from a Viennese woman named Mrs. Simon in her house in Kew Gardens, Queens, where they learned how to make a delicious nut torte. My parents and Saul and Carole also spent occasional weekends at an inn in Pine Plains, New York, called Monblason, where the French owner/chef Charles Virion whipped up fabulous feasts. In January 1968, my parents, together with Murray and his wife, Edith, finally made it to Europe, eating their way across the Atlantic on the S.S. France, where there was unlimited caviar at dinner.

I, too, was swept up by the thrill of French food and became particularly enamored of French pastry. My ideal was the strawberry tart log at Patisserie Dumas in Manhattan. It was a rectangle of buttery, feather-light mille-feuille pastry spread with a layer of silky crème anglaise and topped with plump, lightly jam-glazed strawberries. It was heavenly, and worth dealing with the imposing cashier who glowered at the customers from her perch behind the cash register.

By the mid-1960s, Zabar’s had become a fashionable place to shop for both gourmet offerings and traditional Jewish appetizing and delicatessen. Actors, musicians, and intellectuals who lived and worked nearby, as well as neighborhood residents, congregated at Zabar’s on the weekends to socialize while stocking up for Saturday and Sunday brunch.

__________________________________

From Zabar’s: A Family Story, with Recipes by Lori Zabar. Copyright ©2022 by Lori Zabar. Excerpted by permission of Schocken, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher

Lori Zabar

Lori Zabar was an art, decorative arts, and architectural historian; a historic preservationist; and an attorney. She was for many years a researcher in the American Wing and the Modern and Contemporary Art department of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as an independent curator and consultant. She passed away in February 2022.