The Complex Grief of Losing a Mother You Already Mourned

Candice Iloh on Coming to Terms with Their Mother as Ancestor

I cannot remember the last time I saw my mother alive before her final week earthside. I can only recall small details like how she sat across from me in my sister’s living room, fidgeting and intermittently gripping the purse that rested in her lap. How she dripped in her favorite color. And the fact that she couldn’t keep eye contact with me. Her head had an unmistakable tremor. Though she’d been recovering from addiction for years, something else was still apparently in her system.

This time it was prescribed by her negligent doctors. The mother I knew as a child had given herself up to some new pill and was long gone. We sat across from each other trying to catch up. My mother wanted to make sure I was doing alright. That I didn’t need anything, so she said. And I wanted her to believe I wasn’t worried. I was fine, I insisted. As always. Without her.

December 25, 2018, Debrah finally died of stomach cancer surrounded by family. I was in my hotel room just a few blocks up the street. Around 9:30 am is when Aunty called. Your mama has gone on to be with The Lord, she’d said. Thank you for telling me, I’d said back. My words were dry and lifeless. It was over. No, I didn’t want to come down to the hospital. No, I didn’t want to be with the rest of the family. I’d already said my own goodbye.

I flew into Peoria, Illinois the week before to wait for the last bad thing to happen. If it were my mother, the Doctor had said, I would come. Code for: you don’t want to regret what you do with this moment. Whatever we had going on could be put aside. For now. My father bought me a plane ticket and said he’d support whatever I chose to do. I chose to book a room at a hotel that was walking distance from the cancer ward. To visit her once every other day. To smoke half a blunt each morning and take a walk around the city like a tourist on all the days I couldn’t deal with going to see her. To make attempts at holding her hand.

She died with her fingernails painted the color she once told me made her feel most powerful. With a plastic bag in her bed that she would cough crimson into. With arguing relatives outside her hospital suite and a folded note that I’d written the night before just under her pillow. What began in her stomach had spread throughout her body and by the time I came to see her on my first day in town she was to the point that she couldn’t believe it was me. I was a mirage to my mother. When she finally accepted my presence, she couldn’t look my way for more than a few seconds. Shame flushed her face.

My sister couldn’t understand why the doctor would halt the blood transfusions and I was ready for what was undoubtedly going to happen next. Aunty tried to hug me in the hallway while I allowed my arms to lie limp at my sides. We weren’t crying for the same reasons, and she would never understand. My sadness was not the family’s sadness. My rage, too ugly for them to hold. They were beginning to mourn someone they would miss, and I already mourned someone I never got to have.

It was over. No, I didn’t want to come down to the hospital. No, I didn’t want to be with the rest of the family. I’d already said my own goodbye.While they were reminiscing the woman she once was, I was wishing the person who was supposed to be my mother had never tried crack cocaine. Or whatever else she’d found in the streets. It was decided early that I would stay with my dad after the last time she sent me to him in the middle of the pre-school year. I was three. After that, anything else I experienced of my mother happened amid a short visit. Sometimes a weekend, never more than a week from what I can remember.

We met with the doctor, who confirmed that my mother had begun the dying process. I decided that evening was going to be my last with her.

I returned to the hospital hours later, pausing in the waiting room while my sister made her way out. Me and mom needed time alone. While I sat there, I pulled out my notebook, a pen, and started writing the note that I would leave with her while she slept. Gratitude spread throughout my body for my loneliness in that moment. There was no one around to comfort me or to ask me if I was ok. I was not. There was no one around to project their feelings on to me about what this moment meant or what I would need. I could say what I wanted here. I could say it without fear, without judgement, without regret.

I could tell my mother that I loved her and that I was sorry for all that had happened to her. I could tell her that I know she did her best. That it was okay for her to go if she was tired. I could tell her that I forgive her and that I’m not mad at her anymore for the choices she made. I was no longer holding on and I did not believe she needed to survive this. I wanted her relief. Tears soaked my everything.

When I was finished, I folded the pages and walked into her room where she was lying with her eyes closed. A large part of me was thankful that she wasn’t awake and that I didn’t have to say what I’d written to her face. Aunty would read my words to her later when I was no longer anywhere near this room. I lifted the edge of her pillow and tucked the letter directly under her head, whispering I love you, Mom, into her ear while I suddenly felt her husband watching me from his cot. He told me to take care on my way out of the room. I was fine with never seeing his face again.

The next morning my mother was dead.

Days prior to all this my cousins and I sat in an empty parking lot passing around a bottle of liquor, waiting for weed. I knew all of us were hurting but it was different for each of us. I enjoyed the comradery of us all feeling this fucked up. For once the level of our family’s dysfunction made sense and felt like home. They made sure I had as much as I needed to numb some of the pain, and no one was going to judge me. No one was going to pull the card of a retired church girl who’d backslid into the family vices. No one was going to ask where the god that had kept me and my father distant from this side of the family all this time was now. Debbie was dying. Just drink. Smoke. What better way to mourn her impending death than to mock sobriety? This was us paying homage.

On the day of my mother’s funeral I stayed in bed crying. It was like I could feel her body being lowered into the ground from where I was. I told my father that it was the worst thing that had ever happened to me. And it was. There is so much about her that I will never know and so much that I am still discovering. Debrah was particular about her catfish. Would sift through the platter for the pieces that were perfectly crispy. Ate cucumber and tomato salads. Chewed and smacked with her mouth open. Wanted to be an interior designer. Watched black and white films because she said the actors in them genuinely looked happy. Met my father at nightclub in San Antonio, Texas a few years before I was born. Became a mother for the first time when she was 14. Was 28 when she birthed me. Was never afraid to curse somebody out or lose a job. Handed me a glass of wine and a cigarette, trying to comfort me, the last time she’d seen someone make me cry over the phone during one of our visits. Fuck that bitch! she’d screamed as she demanded I hang up the phone.

Beyond these moments, most of what I know about my mother are stories passed down and things I witnessed without explanation. Her disappearing for hours and returning with a different personality. Holding me in the middle of the night, crying as her pores reeked of salt and alcohol. Threatening to cut her second husband in half with the chef’s knife she’d grabbed from the kitchen sink at a random turn in a conversation.

Several times when family told me not to react. Be still. Let her “episode” pass. Don’t be like her, they would say. And in the same breath, she is still your mama. You only got one. No one said schizophrenia. No one dared say she is high. It would be decades before I’d label any of her behaviors as spiraling, mania, overdose, psychosis. Sometimes my brain will taste a faint memory of the ketchup in her meatloaf from that one time I visited her former home in Arizona. Or catch a whiff of bacon smoke that still lingered the night that I woke to her sobbing in the bathroom alone. At moments her scent will rise faintly from my body.

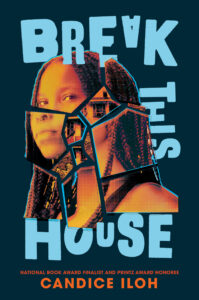

Debrah didn’t go until she was ready. Until I was ready. My mother, now my ancestor. Her pain a road map. A warning sign.What I learned last year while writing Break This House is that I am just at the start of a lifetime of grieving. How I will look in the mirror and catch glimpses of a woman who I barely knew but whose pain feels more than familiar. That there will be times I hear her voice when I open my mouth and, when I’m triggered, she will show me her face. She will haunt me, making sure I never forget that she once existed below the clouds in a world that did nothing but take from her. Debrah didn’t go until she was ready. Until I was ready. My mother, now my ancestor. Her pain a road map. A warning sign.

I wrote this second novel after decades of putting our shared suffering away because I realized my mother’s story existed long before mine. It occurred to me that her reasons deserved space, time, dignity. Before I was ever born, she was a girl who became a mother at such an early age that survival was a priority before she could ever consider how she wanted to live. I think about myself at that age unable to imagine the purgatory of having to be responsible for another life. Having so few ways out and few places to put it all.

Suddenly substance abuse—wanting to flee your responsibilities—makes a whole lot of sense. Neglecting your second child so you can have some semblance of freedom, too, makes sense. I wrote a story about a girl whose mother turned her back on her right before her eyes. Seemingly overnight. Mine fell apart over time while I pieced together side conversations and whispers. I think she’s using that stuff, they’d said. She’s probably dabbled in it all to be honest, they added eventually. I unpacked my tendencies for addictive behaviors as I struck my keyboard in the middle of the night and, as I strung together sentences that shaped my protagonist’s mother, I wrestled with my own love for the sweet, reckless feeling of escape.

I know my mother loved me even though she couldn’t give me what I needed. Even though she managed with so few tools. She is teaching me so much about myself from wherever she is now. She is teaching me how to cope in ways that don’t cause irreparable damage, how to watch my body’s responses to the world like a compass, and how to let things that once felt good go when they stop being a sustainable balm. How to sense when pleasure has developed into self-harm.

And I will never forget the better, simpler days. Peanut butter cookies with the fork markings in one of her friends’ kitchens. Trying on my first lace training bra that I just had to show everyone. Shaving my legs in her bathtub for the first time against my father’s wishes. I will never forget the sound of her voice. Her big laughter will never fully leave me. I will never forget the fight she had when she was still determined to stay. I now know, with great understanding, that she tried.

_______________________________________

Candice Iloh’s Break This House will be available May 24 via Dutton Books for Young Readers.