How Yoga Carries Its Own Legacies of Violence

Fariha Róisín on Understanding Caste Supremacy and Teaching Yoga in the West

Feature image © The Trustees of the British Museum

I have been practicing yoga on and off since the age of thirteen, more than half my life. It was my entry point into the wellness world. Like a calling—maybe an ancestral longing that I’ve had my entire life—as a child capsized in diasporic ambivalence, yoga and meditation felt like portals into a lost, ancient self.

Perhaps it was also the closest tangible understanding that I had to being South Asian.

This comes back to yoga only because there’s a responsibility (in literally the act and understanding of yoga) to hold multiple truths. “No man is to be judged by the mere nature of his duties, but all should be judged by the manner and the spirit in which they perform them,” writes Swami Vivekananda in Karma Yoga. “We shall find that the goal of duty, either from the standpoint of ethics or of love, is the same as in all the other yogas, namely, to attenuate the lower self so that the Higher Self may shine forth, and to lessen the frittering away of energies on the lower plane of existence so that the soul may manifest them on the higher planes.”

To teach yoga in the West, especially if you are not of South Asian heritage, by definition means you are appropriating it. However, the conversation of yoga rarely furthers the dialogue of how do we deal with the mass co-opting of Indian culture? Especially when yoga itself is unknown to so many of the people it belongs to.

The continuation of teaching a sanitized history of yoga is dangerous on many levels. If your yogic practice doesn’t engage with the vast historical truths of yoga, if it doesn’t make space for how these ancient practices were vilified—only to be co-opted by nations that perpetuated in quashing this knowledge so that Indians would lose their access to be well—then you are participating in an exploitative and unethical practice that is inherently, by definition, anti-yoga.

To teach yoga in the West, especially if you are not of South Asian heritage, by definition means you are appropriating it.

In early 2021, India was hit with some of the most devastating Covid numbers, and writer Meera Navlakha wrote in gal-dem, “On 22 April—the same day Archana Sharma was trying to find oxygen for her struggling family—India reported the highest daily increase worldwide (314,835) in Covid-19 cases since the beginning of the pandemic. Hours later, India’s capital, Delhi, announced there were just 26 vacant ICU beds across the city.

And, despite India being the largest Covid-19 vaccine manufacturer in the world, the country is facing a dire shortage of jabs as it is forced to fulfill export contracts to the US and Europe.” She added to these harrowing details: “All Indians have left are each other and their social networks. It is a damning reflection of the country’s lack of preparedness to save its citizens.”

This is a civilization that had answers to its own wellness inquiries only to have them stolen and profited off of, while it now as a colonized society suffers. It’s not right. On top of this, so many of us, like my family and parents, are still in a process of grief absolutely rooted in the devastating impacts that colonization has had on migrants. A disconnection from the homeland has given so many of us a disconnection from self and therefore an understanding of who we are, which leads to both a philosophical and spiritual dilemma that continues to impact the well-being and psyche of my people.

Given the surge of Hindutva supremacy in India, a fascist-led movement, it is an urgent reminder that a holistic understanding of yoga—and therefore India—is immensely necessary. Yoga itself is a varied discipline compiled over thousands of years of thought that sometimes contradicts itself. Similar to the dynamics of racial segregation, caste was born out of Hinduism in India and is “one of the world’s oldest social hierarchies, ordering society based on purity laws. A person is born, raised, and dies in the caste their family is assigned to, with doctrines of karma and dharma justifying extreme differences in qualities of life,” writes my cofounder at Studio Ānanda (an online archive on wellness), Prinita Thevarajah.

Given the growing instability across India, it’s important to understand that the origins of these ancient practices are still steeped in present-day atrocities. “Brahmin priests and teachers hold the highest status, and lower caste communities (considered ‘untouchables’) are made up of Dalits and indigenous Adivasi communities.” This is a living reality for Indians in India, and it’s important that we carry this understanding as we move toward global liberation.

Though caste was constitutionally abolished in 1950, “marginalization against lower caste communities has been historically consistent, with segregation, discrimination in opportunities, and a higher violence rate common against lower caste communities. Research estimates crimes against a Dalit person occur every 18 minutes, with 21 Dalit women being raped each week in an act of caste supremacy.” The last figures are the most jarring and go back to power and oppression used against femme bodies across the world. “The right performance of the duties of any station in life, without attachment to results, leads us to the realization of the perfection of the soul,” writes Vivekananda.

This dislocation from the truth of spirituality can be seen throughout the world. Muslims are misusing the words of the Qur’an from Saudi Arabia onward. Buddhist monks are killing Rohingyas in Myanmar. I’m not trying to moralize—humans, by nature, are flawed. This is why we must engage with ourselves holistically so that we can continue to tell the real societal truths that haunt us but need to be faced. This means all of us get to talk and all of us are required to listen, to each other. No voices are prioritized over others, so we have a chance at healing by telling the whole truth, our whole truths.

We deserve to return to the people we were before we were told we were inherently wrong. We need to return to a time when we were invested in ourselves as people; when it mattered if you were a good person. If that time in history has never happened, why aren’t we all actively jumping toward that possibility? Is it just our unevolved and unchallenged nature holding us back? Or is it something more? Like our collective traumas?

Yoga originates from practical and personal teachings documented in the Vedas, which are “considered the most sacred and treasured spiritual texts of India,” but it is the handbook of the Upanishads (which contains over two hundred scriptures) where wisdom of the Vedas is transferred into personal and practical teachings.

It’s interesting to see how hatha yoga has been propagated in the West, completely devoid of any of this history of its tricky origins and complicated evolution.

This practice was slowly refined and developed by the Brahmans and Rishis (mystic seers), and the most renowned of the yogic scriptures is the Bhagavad-Gîtâ, composed around 500 BCE. “Though it virtually ignores postures and breath control,” writes David Gordon White in “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea,” “devoting a total of fewer than ten verses to these practices. They are far more concerned with the issue of human salvation, realized through the theory and practice of meditation.”

Over the years interpretations of yoga have shifted, evolved, and changed, but at the foundation, White suggests, “Yoga is an analysis of the dysfunctional nature of everyday perception and cognition, which lies at the root of suffering, the existential conundrum whose solution is the goal of Indian philosophy.” Even still, this history is complicated. White also adds, “The gulf between yoga practice and yogi practice never ceased to widen over the centuries.

In later, esoteric traditions, however, the expansion of consciousness to a divine level was instantaneously triggered through the consumption of forbidden substances: semen, menstrual blood, feces, urine, human flesh, and the like.” White explains the “menstrual or uterine blood, which was considered to be the most powerful among these forbidden substances, could be accessed through sexual relations with female tantric consorts.

Variously called yoginis, dakinis, or dutis, these were ideally low-caste human woman who were considered to be possessed by, or embodiments of, Tantric goddesses.” It’s a complicated history that dips in and out of tradition and focus, which is why it’s extremely interesting to track these shifts of perception that rely on caste in ritualized aspects as well.

Later “a new regimen of yoga called the ‘yoga of forceful exertion’ rapidly emerged as a comprehensive system in the tenth to eleventh century, hatha yoga is entirely innovative in its depiction of the yogic body as pneumatic, but also a hydraulic and a thermodynamic system.” This shows that as yogic principles shifted, discourse about evolution did as well.

And yet, when the British rule began in 1773, according to sociologist and yoga practitioner Amara Miller of the Sociological Yogi, the hatha yogis “were associated with black magic, perverse sexuality (based in tantric philosophy), abject poverty, eccentric austerities, and disreputable, sometimes-violent behavior. The British government banned wandering yogis, trying to promote more ‘acceptable’ religious practices such as meditative Hinduism common among the educated and upper classes.” Meaning a quieter, more subsumed, version. These policies were supported, of course, by wealthier Indians who hoped assimilation would save them.

As the scope of colonial police powers grew in India, poor hatha yogis were increasingly demilitarized and forced to settle in urban areas where they often resorted to postural yogic showmanship and spectacle to earn money panhandling.

From that point onward, “hatha yoga practices became associated with the homeless and poor, and were considered by both the British and Indians ‘not only inferior but parasitic on other, worthier expressions of yoga that foregrounded meditative traditions.’” It’s interesting to see how hatha yoga has been propagated in the West, completely devoid of any of this history of its tricky origins and complicated evolution.

Yet we must note these changes and adaptations in order to hold the multiple truths of these regions and understand South Asia more complexly. Swami Vivekananda was a Bengali Hindu monk and chief disciple of the nineteenth-century Indian mystic Ramakrishna, who was also a Bengali Hindu mystic. From his teachings, Vivekananda learned that all living beings were an embodiment of the divine self; therefore, service to God could be rendered by service to humankind, a beautiful and integral sentiment.

“Our various yoga do not conflict with each other; each of them leads us to the same goal and makes us perfect; only each has to be strenuously practiced,” writes Vivekananda. I understand “strenuously practiced” as the diligence to continue evolving, to grow, to learn. And though there are many anti-casteism movements within Hinduism, it’s particularly pertinent for those who teach and engage with yoga in the West to understand that white supremacy and caste supremacy are interlinked and that yoga carries its own legacy of violence. To deny the past is to actually deny the total reality. We can’t keep living in these fractured interpretations of ourselves or our culture.

__________________________________

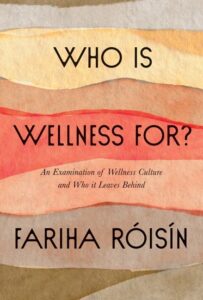

From Who is Wellness For? by Fariha Róisín. Copyright © 2022 by Fariha Róisín. Published by Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Fariha Róisín

Fariha Róisín is a writer, culture worker, and educator. Born in Ontario, Canada, they were raised in Sydney, Australia, and are based in Los Angeles, California. As a Muslim queer Bangladeshi, they are interested in the margins, liminality, otherness, and the mercurial nature of being. Their work has pioneered a refreshing and renewed conversation about wellness, contemporary Islam, degrowth and queer identities and has appeared in Al Jazeera, The Guardian, Vice, Village Voice, and others. Róisín has published a book of poetry entitled How To Cure A Ghost (Abrams), a journal called Being In Your Body (Abrams), and a novel named Like A Bird (Unnamed Press) which was named one of the Best Books of 2020 by NPR, Globe and Mail, Harper’s Bazaar, a must-read by Buzzfeed News and received a starred review by the Library Journal. Their first work of non-fiction Who Is Wellness For? An Examination of Wellness Culture and Who it Leaves Behind (HarperWave) was released in 2022, and their second book of poetry Survival Takes A Wild Imagination came out Fall of 2023. They are a member of Writers Against The War on Gaza.