How Writing My Books Helped Me Understand My Chinese Parents

Janie Chang on Preserving Her Family History Through Historical Fiction

I was one of those: a rebellious teenager with traditional Chinese parents. I chafed at my father’s strictness, at his expectations of absolute obedience, his insistence on perfect grades. I ran in the opposite direction, leaving home almost as soon as I got my first job. Both my parents are gone now and to my everlasting regret, I realize I never really knew them as people, only as parents. In any case, I’m not sure it would’ve been possible for us to relate to each other any other way than as parent and child.

That’s how it was in Chinese families of my generation, our parents survivors of the Second World War who managed to leave China and move to Taiwan before the Bamboo Curtain fell; we, their children, born in Taiwan with more freedom and prosperity. Even so, our roles and relationships remained defined by the hierarchy of family.

To do the job well, historical novelists must learn about the conventions of an era, the social and political tensions of the time even if these are only used to sketch out the background.

Unexpectedly, writing historical fiction has given me a way to understand them better. With each book I’ve written, researching various aspects of history has turned up insights that were either unexpected or deepened my understanding of the currents that shaped my parents’ beliefs and decisions.

My parents grew up in a China that was near-feudal. As young adults, they survived wartime conditions harsher than anything we could ever imagine. All of this I understood but only in an abridged and abstract way. How did it feel to be a refugee in Shanghai under Japanese occupation? What was it like to live in small-town China just after the fall of the Qing empire? The stories I chose to write all seemed to require research that helped answer those questions.

To do the job well, historical novelists must learn about the conventions of an era, the social and political tensions of the time even if these are only used to sketch out the background. We unearth details that give authenticity and life to the story.

Readers often assume that a Chinese upbringing means I’ve absorbed all kinds of facts about Chinese history and shouldn’t have to do much research, but alas no. My education abroad and in Canada has been of the Western sort, with not much in the way of Asian history. And while I’m lucky to be able to draw on family stories for inspiration, this does not mean a free pass from doing the research. It’s still important to get dates and historical events right, to validate oral history against recorded history for context.

Many of these tidbits from ancestral stories found their way into my novels but it was research that did the most to fill in some of the blanks when it came to understanding my parents.

First, a bit about those family stories. When I was a child, my father recounted tales about our ancestors, and his stories were so fantastical they seemed like fairy tales. There was my seven-times great-grandfather who saw a dragon and spoke to immortals and later became an immortal himself; there was the many-times great aunt whose shame at not producing a son pushed her into insanity; we had one ancestor who saw a ghost dancing across the roof of their house when he was a little boy. I also loved hearing my father reminisce about his own youth, word pictures of what his home town was like and how his university became a travelling campus of refugee students during the war.

Many of these tidbits from ancestral stories found their way into my novels but it was research that did the most to fill in some of the blanks when it came to understanding my parents.

For my debut novel, based on my paternal grandmother’s hauntingly tragic life, one research topic was about her cousin, Qu Qiubai. Although his branch of the family was very poor, Qu became a writer, poet, translator, and a political activist. Along with a Russian colleague, he developed the Sin Wenz system of Mandarin romanization and he also translated the lyrics of The Internationale into Chinese, now used as the anthem of the Chinese Communist Party. He was the acting leader of the Chinese Communist Party from the late 1920s to early 1930s, before Mao Zhedong. He died at 36, executed by the Chinese Nationalists. Now his home is a museum and he’s considered a hero of the Communist revolution.

In Three Souls, I wrote him as a character who was a leftist poet, a womanizer whose only true loyalty lay with his politics. As for my grandmother, it was clear that she came from a long line of distinguished intellectuals and felt it her duty to make sure her children went to university even as the family slid into poverty. It was also clear that she had passed this conviction on to my father, who was insistent—even more so than the average Asian parent—that we all graduate from university. For him this had been a hard-won achievement, determinedly pursued through years of war and poverty, out of obedience and love for his mother’s wishes.

These were the experiences that gave him nightmares so horrible that sometimes he would shout himself awake at night.

While researching Dragon Springs Road, I learned how mixed-race children in China were scorned by both Chinese and white society. The mothers were usually poor women or prostitutes, the children generally given up for adoption to orphanages, many of them run by foreign missionaries. This brought back family gossip and hesitant bits of information about my mother’s beloved grandfather, my maternal great-grandfather. My mother didn’t speak of her grandfather very much, although it was evident she had adored him. She said only that he had been a pastor, one of the first Chinese Christians to attend seminary school.

There were hints that he had been an orphan, and comments that his daughter, my maternal grandmother, had been tall with rather foreign features. I decided to get a DNA test and it came back confirming that I have European genes. Today, this hardly raises an eyebrow. In those days, however, it was a cause for deep shame, a topic to be avoided. It explains my mother’s reticence in talking about her grandfather.

Editors like the “unknown episode of history” hook and it turned out my father was part of the largest exodus of academics in history. It was an amazing, unique chapter in history, yet totally unknown outside China. When Japan invaded China in 1937, seventy-seven Chinese universities packed up their libraries, students, and staff to flee inland. They took whatever transport was available, walked a good part of the time, trailing behind carts piled full of books, laboratory equipment, and even livestock from agricultural programs. They continued their lessons while on the move, the professors setting up class in fields or temple courtyards.

While researching The Library of Legends, I was fortunate to find a compilation of memoirs written by the alumni of one of those universities (not my father’s). Their accounts gave me shivers of recognition—their experiences echoed my father’s stories. I also realized that my father had glossed over the hardships he’d suffered, the constant hunger and cold, the fear of running into Japanese soldiers, the political pressure being put on students to join one party or another. He had turned them into amusing anecdotes suitable for a small child. The book of memoirs did not hold back. These were the experiences that gave him nightmares so horrible that sometimes he would shout himself awake at night.

Research is no substitute for listening to a first-hand narrative.

My parents weathered social and political forces which were at times brutal, at times liberating, the changes happening at a pace so bewildering that all they wanted for the rest of their lives was some stability, some safe corner of certainty for our family. I only half-understood the influences that formed their world view, and after writing historical fiction, I understand a little bit more. But only just a little bit. Research is no substitute for listening to a first-hand narrative.

Perhaps the message is this: oral history is ephemeral. Someone dies and that knowledge is lost. Someone loses their memory and that knowledge is lost. My advice? Don’t wait to talk to your elders and don’t worry about writing it all down. What matters is preserving the information. “Interview” them and use audio or video recordings to capture the conversation. You may not care about it right now but when you’re older, believe me, your family history will matter—even if you’re not writing historical fiction.

__________________________________

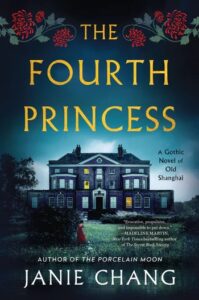

The Fourth Princess by Janie Chang is available from William Morrow Paperbacks, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Janie Chang

Janie Chang is a Globe and Mail bestselling author of historical fiction. Born in Taiwan, Chang has lived in the Philippines, Iran, Thailand, New Zealand, and Canada. Her novels often draw from family history and ancestral stories. She has a degree in computer science and is a graduate of the Writer’s Studio Program at Simon Fraser University. She is the author of Three Souls, Dragon Springs Road, The Library of Legends, and The Porcelain Moon; and co-author of the USA Today bestseller The Phoenix Crown, with Kate Quinn. Connect with Janie on Instagram at @janiechang33, on Facebook at @JanieChangWriter, or via her website, janiechang.com.