How Writing a Children’s Book is an Antidote to Doomsday Thinking

Ben Okri on Imagining the Impossible

An unspoken tradition hints that going to the source is good for the story you want to write. The trouble often is that we have no idea what that source may be. Sometimes we think it is sheer research and we spend time in libraries. Often, we think it’s where the action of the proposed work takes place. So, like Hemingway, we go to battles or bullfights. I think these are useful if you can do them or afford the travel, though there is a fallacy involved in thinking that the world, in and of itself, is the constant source of infallible research, when the world changes from day to day.

When I came to writing Every Leaf a Hallelujah, a book for the eternal child in us, I pondered how I was going to tell this tale. I knew I wanted to set it in the outskirts of Lagos. I knew its heroine would be a young girl. I didn’t have the story, only a strong impulse to tell a tale about trees and forests and our relationship to nature. For many weeks nothing happened. But I did not despair. I have found that despair never helps creativity. What helps is a certain calm. I always wait for that calm. I let the fretting and anxiety pass. I avoid those people who make it their duty to make you anxious. I go for long walks. I empty my mind. I swim out beyond the turbulence of my being to where the sea is calm within me. When I get to this calm place, I ask the question: what is this story? What is my being aching to express? And then I wait and listen.

I think the uncertain nature of the art of writing makes writers wary and even frightened of waiting. Worse than that, we are not taught to listen. But listening and waiting are invaluable. I am not waiting for inspiration. It cannot be waited for. Inspiration tends to come to you, tends to trouble you, when you have prepared for it. What I am listening for is a voice, a tone. What I am waiting for is a pulse.

Then one day, while I am busy with something else, as Tchaikovsky said somewhere, I hear it. Then without waiting, without hesitation, I begin. I submit myself to that impulse. Something is doing the writing inside me, but my brain is guiding it, modulating it. I am no longer listening. I am inventing.

Writing is that child’s footsteps towards what seems impossible.

When you enter a story in the right way, it tends to write itself. There is an inner logic to every story that contains in it everything you want to say in the story, and things you did not know you were saying. I believe every story has a spirit that helps it to be born. The art and the craft is the amplification or even the purification of that birth.

As the story grew, I felt the need for nature. I would walk in parks and sit at the foot of trees. Some trees were especially attentive to my mood. While writing the book I saw trees differently. It got so I could see them smile. When the sun is shining and a gentle breeze blows the tops of trees and you are far enough away so that you can see the treetop as a whole, it is possible then to see a tree smiling. It is a fleeting vision. Then the leaves and branches become what they always seemed.

While writing the tale I also noticed that trees are worlds of stories. Trees taught me about stillness and tranquillity and letting things come through you.

After over forty years laboring in the vineyards of literature, writing Every Leaf a Hallelujah gave me the priceless gift of the courage of childhood, the difficult gift of simplicity.

We live in a world where every day we are ruining the immeasurable heritage of the earth‘s beauty. Our civilization has become, in climate crisis terms, suicidal. Our cars, our food, our holidays, our technologies, are contributing to the destruction of our ecosphere. The Amazon is perishing daily.

No one will feel this looming tragedy more than those who today are children. Every day that I wrote my five-year-old daughter would come to me and ask if Mangoshi, the seven-year-old heroine of the book, has saved the forest yet. Through her I saw that it is wonder that we need, and that the great feat of turning our civilization around so that it enhances nature rather than destroys it can begin with a child’s footsteps towards an impossible hope. Everyone, it seems, can do something small that would add up to the great change we need to save this magical globe that is our blessed home.

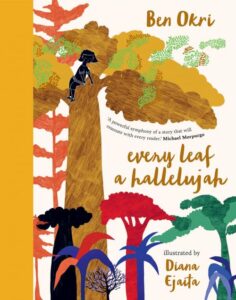

(The book has also been graced with the magical illustrations of Diana Ejaita, a frequent contributor to The New Yorker, who drew her inspiration from the forests of Africa.)

For me, now, writing is that child’s footsteps towards what seems impossible. Every Leaf a Hallelujah is a love letter to the eternal child in us: the one who reads, loves, knows the possibilities of change, and believes in the renewing power of nature.

__________________________________

Every Leaf a Hallelujah by Ben Okri, illustrated by Diana Ejaita, is available via Other Press.

Ben Okri

Ben Okri is a playwright, poet, novelist, essayist, short-story writer, anthologist, and aphorist. He has also written film scripts. His works have won numerous national and international prizes, including the Booker Prize for Fiction. His books include the eco-fable Every Leaf a Hallelujah, the genre-bending climate fiction Tiger Work, the poetry collection A Fire in My Head, and the novels Astonishing the Gods, The Last Gift of the Master Artists, and Dangerous Love.