How Worried About Virtual Reality Should We Be?

Oh Cool, Fully Immersive Digital Platforms for Everyone!

Whenever a new technology hits the market—particularly technologies designed to deliver new forms of content to consumers—there is always a sizeable (and often vocal) percentage of skeptics who worry about its impact on society. In 1909, for example, Nobel Laureate Jane Addams gave voice to a widespread concern that a new medium called “film” was corrupting children. “Three boys,” Addams wrote in an essay called “The House of Dreams,” “who had recently seen depicted the adventures of frontier life including the holding up of a stage coach and the lassoing of the driver, spent weeks planning to lasso, murder, and rob a neighborhood milkman . . . such a direct influence of the theater is by no means rare even among older boys.”

A few decades later, a similar sort of national panic emerged when televisions began popping up in middle-class homes around the country. For instance, a 1954 Gallup Poll showed that 70 percent of Americans believed that “mystery and crime programs” contributed to adolescent problems, particularly juvenile delinquency. (Interestingly enough, this came only nine years after a previous Gallup Poll had revealed that only one percent of Americans knew what a television was).

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, concerns about technology tended to focus on how media and new mediums affected children. In the second half, however, technophobia became more of an existential concern—a sentiment that can be seen in a major survey that Time conducted in 1971 to determine the public’s attitudes towards computers, which found that:

- 54% thought that computers were dehumanizing people

- 33% believed computers were decreasing freedom

- 23% expected that computers might disobey their programmers in the future.

Over the years, people started to become more comfortable with computers in their lives, but this was by no means a quick transition. “As many as 30 percent of our population are cyberphobiacs,” Professor Sanford Weinberg told Computerworld in 1982 (11 years after Time‘s survey). The article then goes onto describe an incident in which a police officer grew so fed up with the computer in his squad car that he ended up literally firing his weapon at it.

Flash forward more than 30 years, and though there have yet to be any incidents of frustrated cops shooting up virtual reality headsets (or increased occurrences of children shaking down milkmen), there are certainly some concerns about virtual reality (VR) and its potential dangers. Many of which are valid, given that Goldman Sachs predicts VR to be “bigger than TV by 2025”— forecasting an $80 billion industry by then—with Heather Bellini of Goldman Sachs Research noting that the tech is “already transforming sectors like real estate, healthcare and education” and has “the potential to transform how we interact with almost every industry today.”

At this moment, we are now three years into the dawn of consumer-quality virtual reality—with Oculus, HTC and Sony each launching high-end, semi-affordable VR headsets in 2016—and, as of now, many of the current worries about this technology focus on the potential health-related risks of putting on a headset.

“Before you or your children try out your shiny new VR gadgets,” CNN’s Sandee LaMotte warned in a comprehensive article entitled The Very Real Health Dangers of Virtual Reality, “be sure you’re fully aware of the potential health risks of this technology.” LaMotte’s piece then goes on to detail a handful of practical concerns, each paired with insights from experts in various fields. For example, Marientina Gotsis, an associate professor of research at the Interactive Media and Games Division of the University of Southern California, notes the logistical dangers that come from losing spatial awareness (“You can trip and hit your head or break a limb and get seriously hurt, so someone needs to watch over you when you are using VR. That’s mandatory.”); Martin Banks, an optometry professor at the University of California, Berkeley, notes some concerns about VR’s impact on eye growth (“Looking at tablets, phones and the like, there’s pretty good evidence that doing near work can cause lengthening of the eye and increase risk for myopia . . . We’re all worried that virtual reality might make things worse.”); and Walter Greenleaf, a behavioral neuroscientist who works with Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, notes VR’s propensity for inducing motion sickness (“In a virtual environment, the way we look and interact is changed because we may be projecting onto the eyes something that looks far away, but in reality, it’s only a few centimeters from the eye . . . and we don’t know the long-term effect of this.”)

Though there have yet to be any incidents of frustrated cops shooting up virtual reality headsets . . . there are certainly some concerns about virtual reality and its potential dangers.

All three of these issues (motion sickness, myopia and loss of spatial awareness) are incredibly valid when it comes to VR, but—call me an optimist—they all seem reasonably addressable. In part because each of these issues can be measured (and then assessed) in somewhat quantifiable ways. Which is why, when it comes to new technologies, the things that usually concern me most are those which cannot be qualified; and why—in the case of virtual reality—I’ve been finding myself more and more thinking about a question I asked my science teacher in 6th grade.

The question itself is not particularly remarkable (although, admittedly, it felt record-scratching and award-winning to my 6th grade self): “What if what I see, when I see the color blue, is not the same as what you see?”

Like I said: I wasn’t going to be winning any Nobel Prizes for this question; but fortunately, Mr. Chipkin provided a thoughtful answer, talking about the concept of “perception”, the notion of our “shared reality” and, ultimately, making the point that—as long as my perception of “blue” and your perception of “blue” remain consistent—the potential difference doesn’t really matter. Because, as long as our individual perceptions remain consistent, then we can still co-exist and interact with ease in the same shared reality.

In 2016, Facebook acquired Oculus—the upstart, Kickstarter-founded VR company—for nearly $3 billion. In a post after announcing the acquisition, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote, “Imagine enjoying a court side seat at a game, studying in a classroom of students and teachers all over the world or consulting with a doctor face-to-face—just by putting on goggles in your home. This is really a new communication platform. By feeling truly present, you can share unbounded spaces and experiences with the people in your life.”

Zuckerberg, here, is talking about the social component of virtual reality. Which, unsurprisingly, was a big part of what led to his interest and investment in Oculus. And—truth be told—the allure of Social VR is a big part of what inspired me to spend the past four years working on a book about Oculus, Facebook and Virtual Reality. I love the idea of being able to put on a pair of goggles and instantly feel like I am with others—to feel present together with my parents (who live in upstate New York), or my brother (in Colorado) or my Aunt and Uncle (in South Carolina). This, to me (and to millions of others), represents the power of VR; the ability to be anywhere with anyone; it’s amazing and enthralling but—if you squint enough at those virtual smiles—it’s also a little concerning.

Because we can’t forget that this promise of tomorrow (already becoming available today) is powered by a platform-maker; and that, in order to monetize their platform, each platform-makers has their own objectives—be they attention, engagement or personal information—and that by collecting all that data (and then using algorithms that can assess and cater to your behavior), those platforms are incentivized to show you the shade of blue that will enable them to collect more of your attention, engagement and personal information. And, hey, maybe that’s not a terrible thing—maybe, deep down, we all want to exist in our own realities—but there will be unintended consequences if and when Social VR takes hold and, two people try to interact in what they perceive as a shared virtual space, but their shared reality is fractured, and it’s fractured by design—giving them more and more of what they “want”; but in ways they don’t even know or understand.

__________________________________

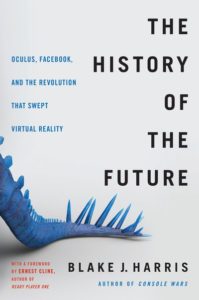

From The History of the Future: Oculus, Facebook, and the Revolution That Swept Virtual Reality. Used with the permission of Dey Street Books. Copyright © 2019 by Blake J. Harris.

Blake J. Harris

Blake J. Harris is the author of The History of the Future: Oculus, Facebook, and the Revolution That Swept Virtual Reality, available now from Dey Street, an Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.