How Wagner Tried to Revolutionize Art and End Capitalism

Simon Callow on a Great Composer Getting Political

The World in Flames

At the beginning of 1848, as Richard Wagner put the finishing touches to his new opera, the world was falling apart again, insurrection erupting volcanically all across Europe like Holy Fire. Wagner’s old revolutionary sympathies flickered back to life. He had rejoiced when attempts to restore the old dispensation had been thwarted in Austria, where students and workers had fought side by side. Wagner celebrated his newfound solidarity by quickly knocking off an incendiary poem which a prominent Viennese newssheet printed. In Saxony, meanwhile, Friedrich Augustus II responded to events by installing a new liberal ministry, which put a fully democratic constitution in place. Not everybody was convinced. Popular opinion in Dresden quickly polarized between constitutional monarchists and out-and-out republicans. The latter established a party which called itself the Patriotic Union (Vaterlands-Verein); August Röckel, Wagner’s associate conductor at the Court Theater, was its leading spirit. Röckel invited Wagner to air his views, which—his taste for public speaking having been whetted by the Weber celebrations—he was only too willing to do.

Addressing some 3,000 people, Wagner argued for a form of constitutional monarchy in which the king was an equal with his subjects; as part of the new dispensation, what he called “the demonic concept of money” would be abolished. The speech roused his listeners to wild enthusiasm, especially passages concerning the “sycophantic” courtiers by whom the king, he said, was surrounded: this was particularly gratifying, of course, coming from the Orchestral Conductor Royal and it went round the city like wildfire. The excitement of the event seems to have gone to Wagner’s head. Never popular in court circles, he was now acquiring serious enemies; that night at the theater he was due to conduct Rienzi, of all things, with its spectacular scenes of popular turbulence. He was warned that there might well be a demonstration against him; instead, he was greeted with a roar of approval. The press entered the fray on the other side, along with the court officials who had borne the brunt of his coruscating oratory; for them he was public enemy number one. He quickly knocked off a letter to the king, pleading thoughtless indiscretion rather than deliberate offense, and was assured that, despite pressure from courtiers, his job was safe. He went to Vienna to try, unsuccessfully, to whip up a production of something of his own there; failing to do so, he seized the opportunity of dropping in on a meeting of one of the most radical groups in the city, blissfully oblivious that his every move was being monitored and reported.

“He became increasingly radicalized, connecting his idealistic views of the position of art in society with Röckel’s vision of a world where the power of capital was annihilated, and class, position and family prejudices would disappear.”

Wagner returned to Dresden to discover the entirely unsurprising fact that there were intrigues afoot to eject him from the Court Theater. Instead of lying low, he sought out Röckel, now dismissed from his job at the theater and editing a firebrand socialist newspaper; Wagner felt an urgent need to discuss the political situation with him. Persuaded by Röckel’s arguments, he became increasingly radicalized, connecting his idealistic views of the position of art in society with Röckel’s vision of a world where the power of capital was annihilated, and class, position and family prejudices would disappear. In the new order, Röckel assured him, everybody would participate in labor according to their strength and capacity, work would cease to be a burden and would eventually assume a purely artistic character.

Inspired by all this, Wagner drew up a plan for a national theater which would be independent of the court, and approached some of the radical new deputies to discuss it. They gave him to understand that determining the position of art, or theater, in the new world they were seeking to bring into being was a rather low priority. Shortly after, he participated in a musical gala at which he conducted the tumultuous, ecstatic finale to Act I of Lohengrin—the first time it had been heard in public. Trumpets blaze and cymbals crash as the king and his men hail the swan-borne hero:

Raise a song of victory

loud in highest praise to the hero!

Acclaimed be your journey!

Praised be your coming!

Hail to your name,

protector of virtue!

You have defended

the right of the innocent;

praised be your coming!

Hail to your race!

To you alone we sing in celebration,

to you our songs resound!

Never will a hero like you

come to this land again!

The women join in, singing:

O that I could find songs of rejoicing

to match his fame,

worthy to acclaim him,

rich in highest praise!

You have defended

the right of the innocent;

praised be your

coming!

Hail to your journey!

This viscerally exciting, headlong climax to the first act of Wagner’s as yet unperformed piece was greeted with muted applause. Nonetheless, he made a fiery speech, sharing with his fellow guests his vision of how the members of the orchestra might be directly and democratically involved in their own destinies. The applause for this was even more muted than for Lohengrin. Heinrich Marschner, composer of The Vampire, who was sitting at the same table, drily expressed doubts as to the desire or ability of orchestral musicians to function democratically. The revolution in the arts, he felt, would not be so easily achieved. In the streets outside the concert hall, revolution seemed all too probable. They were milling with demonstrators, among them Austrian dissidents Wagner had met during his recent visit to the radical cell in Vienna. They appeared at the theater one night asking for tickets for Rienzi, which he duly arranged. That night in the theater, and indeed whenever Rienzi and Tannhäuser were performed, Wagner was cheered to the echo. He had become something of a popular hero. He knew this could bode no good for him, so he was deeply surprised when, during this period of political uncertainty, he was asked by the Opera Intendant to submit Lohengrin for production. The offer was withdrawn almost immediately: the court was now, as he suspected, implacably opposed to him.

Against this incandescent backdrop, he continued to discharge his duties as conductor punctiliously, conducting Bellinis and Meyerbeers as required; but the theater, with all its inadequacies and intrigues, utterly disgusted him: he was now dead to the job. As the political situation grew edgier by the day, he started writing a new libretto based on a story of which, he said, he had been half-afraid, but which now demanded to be written: the 15th-century saga of the Nibelungen, which describes the turbulent life and death of the great hero, Siegfried, against a backdrop of gods and dwarves, dragons and giants. Writing flat out, he compressed the vast mass of material into a fast-moving text, starting with Norns spinning the web of destiny, and ending with Rhinemaidens reclaiming the gold stolen from them by the Nibelungs, as Brünnhilde, lover of Siegfried and daughter of Wotan, chief of the gods, triumphantly conveys her lover’s dead body to heaven in her chariot. Despite its provenance, Wagner’s libretto was no antique fable: in it he was graphically describing what he saw all around him: the collapse of the old world order. Siegfried’s Death, he called it; he wrote as if possessed. And then, as an afterthought, he knocked off a treatment for a play about Jesus Christ as a social revolutionary.

He knew that his tenure at Dresden could not last much longer. On Palm Sunday 1849, despite the ever-growing turmoil all around, he went ahead with the scheduled performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony; the finale, with its great hymn to brotherly love—“Seid umschlungen, millionen!” (“Be embraced, you millions!”) had an overwhelming—a desperate—intensity; spurred on by him, singers and players rose heroically to what he had said was required: “the correct state of ecstasy.”

Joy, O wondrous spark divine,

Daughter of Elysium,

Drunk with fire now we enter,

Heavenly one, your holy shrine.

Your magic powers join again

What fashion strictly did divide;

Brotherhood unites all men

Where your gentle wings spread wide.

During the fervent applause that followed, a colossal, bearded figure suddenly emerged from the audience. It was the Russian anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin, the most notorious terrorist in the world, the Osama bin Laden of his day, with a hefty bounty on his head. He strode down to the orchestra pit and, turning to the audience, announced in a loud voice that “even if everything else is going to be destroyed in the coming conflagration, we must save this.” Wagner had first met Bakunin at Röckel’s, where he had listened, half-enthralled, half-appalled, as the great bearded giant calmly proclaimed the destruction of the world: London, Paris, St Petersburg, all reduced to rubble. What place would art have then? Wagner thought to himself. He found it unbearable to contemplate the demolition of his ideals and hopes for the future of art, and yet the destruction of a corrupt and discredited world order was irresistibly attractive. Bakunin provoked constantly fluctuating emotions in Wagner: from involuntary horror to magnetic attraction, a not entirely dissimilar reaction to the emotions he himself provoked in others.

The political situation was heading towards a catastrophe. Wagner confessed to experiencing a strong impulse just to give himself over to the stream of events, wherever it might lead, as he had done 20 years earlier during the 1830 riots; something fundamentally inchoate in his temperament was excited by movement of any kind, activity, explosions, destruction. Things were moving at a giddying pace. Parliament had been dissolved by a new, reactionary ministry; Röckel was forced to escape. Wagner took over the running of his newspaper, the Volksblätter (the People’s Press); at a committee meeting of the Vaterlands-Verein which Wagner attended as the paper’s representative, there was a practical discussion about weapons, who should bear them and when. Wagner was loudly in favor of issuing guns to all the revolutionaries. In the middle of the discussion the tocsin bell sounded and they all rushed out onto the street. Wagner headed straight to Tichatschek’s house to borrow his rifle, but the singer, a keen hunter, was on holiday and had taken it with him. Frau Tichatschek was in a state of terror at what might happen—perfectly reasonable in the circumstances, but her fear unaccountably provoked Wagner to uncontrollable laughter. Over the next few days he allowed himself, unarmed, to be carried along by the crowd, keenly interested, but not participating, he said, though there is evidence that he and Röckel had ordered a substantial number of powerful hand grenades from the iron-founder Oehme; supposedly intended for Prague, they were in fact kept in the Volksblätter offices, where Oehme primed them.

“Despite these dramatic developments, people continued ambling unhurriedly about the streets. It all felt like a fascinating piece of theater.”

As the situation grew more and more dangerous, the government appealed to Prussia for help in controlling it. There was a move among the radicals to persuade the Saxon troops to declare for the parliament. Wagner impulsively organized a demonstration in favor of this, getting the paper’s printer to run up a banner for him emblazoned with the words “ARE YOU ON OUR SIDE AGAINST THE FOREIGN TROOPS?” As he stood holding the banner, out of the corner of his eye he saw Bakunin strolling around, chewing a cigar, and scoffing at the feebleness of the improvised barricades. A couple of days later, a large crowd proclaimed a pan-German constitution. Despite these dramatic developments, people continued ambling unhurriedly about the streets. It all felt like a fascinating piece of theater, Wagner said, until the terrifyingly proficient Prussian troops arrived and shooting started in earnest. When this happened, Wagner climbed up the Kreuzkirche Tower in the centre of town to get a clear view of what was going on—or to save his bacon; either or both is possible. He kept vigil there all through the night, while the tower’s great bell clanged incessantly, and the Prussian rifle shot beat against its walls. The following day, after some particularly violent skirmishes, the old Opera House, the scene for Wagner of so much misery, intrigue, and frustration, went up in flames, which gave him deep satisfaction; the fire seemed to have taste, he noted, because once it had consumed the unlovely Opera House, it stopped short of the beautiful Natural History Museum and the formidable armory. On Sunday morning he went home, to Minna, and their house in the suburbs, but later that day he went back to Dresden, irresistibly drawn to the battle, which the insurrectionaries were now losing. A provisional government had been established under the leadership of Otto Leonard Heubner; he had appointed Bakunin as his adviser. But this was fantasy: backed by the Prussian military, the Saxon government swiftly regained control and the revolution was over before it had begun.

Bakunin, Röckel and their colleague Heubner fled by carriage to the Saxon city of Chemnitz for safety, but they were betrayed, arrested and condemned to death. Wagner was following just behind them in a second carriage; seeing what had happened to Bakunin, he hopped carriages and made a swift exit to the adjacent state of Weimar, where Franz Liszt—staunch champion of the musical avant-garde, whom Wagner had befriended in Paris—was planning, as “Kapellmeister Extraordinaire” to the court, to stage Tannhäuser.

On arrival in Weimar, Wagner was warmly embraced by Liszt, and even shook hands with the art-loving grand duke and duchess, who were courtesy itself. It soon became apparent, however, that he would not be able to stay there: all the states of the German Confederation—including, in its polite, apologetic way, Weimar—were fiercely united against revolutionaries, and that was what Wagner was now. He had a secret meeting at the border with a tearful Minna, who was understandably reproachful: their comfortable, respectable life in Dresden, everything she had ever dreamed of for them, gone, and for what? But Wagner had no time to dawdle; flight was imperative. Liszt supplied him with a false passport, and he was smuggled out of the country in the guise of a certain “Professor Widmann.” This subterfuge appealed to Wagner immensely. Widmann, his passport declared, was Swabian, and so, with typically madcap humor Wagner, at this moment of possibly mortal peril, did his best to affect a Swabian accent. It defeated him; happily, none of the border guards noticed, and he slipped onto the waiting steamer. Before long he was on neutral Swiss soil, in Zurich. It was 11 years before he next set foot in Germany; and another two years after that before he was admitted back to Saxony.

__________________________________

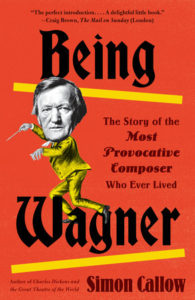

From Being Wagner: The Most Provocative Composter That Ever Lived. Used with permission of Vintage. Copyright © 2017 by Simon Callow.

Simon Callow

Simon Callow made his stage debut in 1973 and came to prominence in a critically acclaimed performance as Mozart in the original stage production of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus at the Royal National Theatre in 1979. He is well known for a series of one-man shows that have toured internationally and featured subjects such as Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, William Shakespeare, Jesus, and Richard Wagner. Among his many film roles is the much-loved character Gareth in the hit film Four Weddings and a Funeral. Callow has simultaneously pursued careers as a director in theater and opera and is an author of several books, including Being an Actor, Love Is Where It Falls, and Being Wagner.