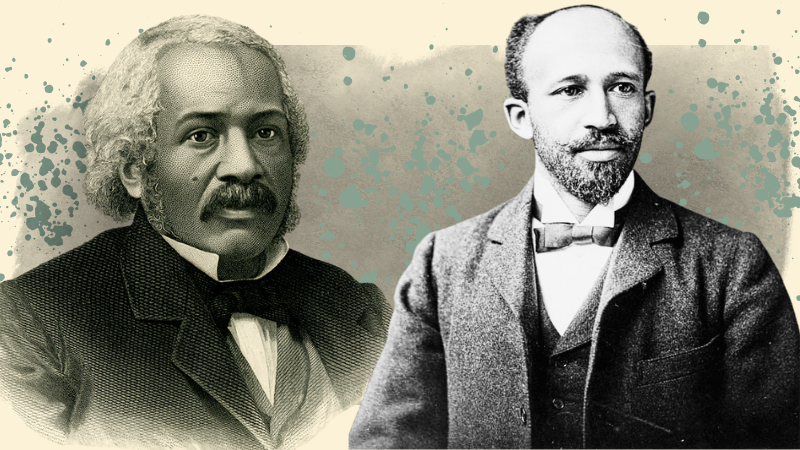

How W.E.B. DuBois and James McCune Smith Helped Combat Medical Racism in America

Michelle A. Williams on Black Contributions to American

Public Health and Sociology

The most prominent of Du Bois’s intellectual influences was James McCune Smith. Brilliant and uncompromising, Smith was a public intellectual with the distinction of being the United States’ first university-trained Black doctor. In 1846, in a stinging and exhaustively researched rebuttal, he showed how John Calhoun’s racist analysis was spurious. Using the relatively new field of biostatistics, along with demographics, he exposed the Southern senator’s questionable claims.

Specifically, he did a spatial analysis using latitude coordinates to show that Black people lived longer in states that abolished slavery, like New Hampshire and Connecticut, than in Georgia where slavery was legal. He also stratified mortality rates by age, race, and place to demonstrate that Black people in New England lived longer than those in the South. And finally, he showed that racial differences in longevity were due to socioeconomic factors and were not inherently biological. “There are sufficient grounds for the belief that the slaves…under all [their] disadvantages, would, if freed from slavery, attain a longevity not very much below that attained by the Europe-American population.”

James McCune Smith was born in 1813 and grew up in the Five Points neighborhood in New York City. He was the son of a South Carolina enslaved woman who fled to New York to escape his father, a wealthy merchant named Samuel Smith who enslaved them both. Young James and his mother lived in constant fear that the slave hunters who patrolled his neighborhood would recapture them. Despite his difficult childhood, his intellectual gifts were obvious.

In the U.S., James McCune Smith was virtually a lone voice, drowned out by the racism deeply embedded in the medical field.

He graduated from the first African Free School, which was funded by the New York Manumission Society, a wealthy group of progressive white men that included Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, but was denied admission to Geneva Medical College (later part of Syracuse University) and Columbia University because he was Black. So benefactors from his days at the African Free School paid for him to attend the University of Glasgow in Scotland, then one of the premier academic medical institutions in the world. He graduated at the top of his class, earning a BA in 1835, an MA in 1836, and a medical degree the following year. Later, a hall at the school would be named after him.

Throughout his life, McCune Smith was a fierce and fearless advocate for the less fortunate. As a young medical student in Glasgow, he was horrified to discover that a senior physician at the hospital where he was training was treating impoverished women suffering from gonorrhea with silver nitrate. This was normally used in low concentrations as a topical treatment, but his superior, Alexander Hannay, was using it full strength internally, which may have resulted in several deaths. McCune Smith exposed the more powerful physician, in two articles in the weekly science journal, The London Medical Gazette, risking his career and jeopardizing his own future. This was certainly not the first, nor would it be the last, time one of our public health warriors took steps toward justice at great personal cost.

McCune Smith never shied away from controversy. In 1859, as the country teetered on the brink of war, he took on one of our most revered founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson, an esteemed intellectual and enslaver who played an early and influential role in the spread of these toxic myths. In 1787, a decade after he helped write the Declaration of Independence, the second president published his widely read treatise Notes on the State of Virginia, in which he questioned whether enslaved people could ever be equal to whites, and advanced his theory that Blacks were inherently inferior, fit to be field hands and little else. The book was perhaps the most damaging and enduring instance of scientific racism in American history, according to historian Ibram X. Kendi.

In his own highly influential pamphlet, McCune Smith refuted Jefferson’s famous query as to whether Blacks and whites could ever live together, and he even challenged the notion of race as a distinct biological category, an assertion that wouldn’t gain common currency for more than a century. Smith began to advance the idea of what we would later call social determinants of health: namely that someone’s health status is largely influenced by the strata of society in which they live, and not because of some innate weakness or strength.

In the U.S., James McCune Smith was virtually a lone voice, drowned out by the racism deeply embedded in the medical field. In Europe, however, reform-minded doctors had begun to look at the social origins of illness and the relationship between the social environment and health. Rudolf Virchow, a doctor in Prussia in the mid-nineteenth century, spearheaded the social-medicine movement.

Virchow already had a reputation as a social reformer and outspoken advocate for public health when he was commissioned in 1848 by the Prussian government to investigate an outbreak of typhus in Upper Silesia, an impoverished region in Eastern Europe where mine workers were being ruthlessly exploited. Typhus had ravaged the local population, and tens of thousands of people died because of the twin epidemics of starvation and disease. Virchow was convinced that typhus had been allowed to race unchecked through the community because poor diets, poverty, illiteracy, and squalid living conditions had made the people more vulnerable to illness—and not because of their “sinfulness” or some inherent inferiority.

After surveying the destruction that had orphaned thousands of children, Virchow produced a blistering indictment of the civil servants whose negligence contributed to “the enormous compilations of misery” that were disturbingly reminiscent of what had happened during the previous decade’s cholera epidemics. “The plutocracy, which draw very large amounts from the Upper Silesian mines, did not recognize Upper Silesians as human beings, but only as tools,” he wrote in his report, which blamed the outbreak on social conditions and the government. Virchow went on to become one of the most influential physician scientists of the nineteenth century, and his pioneering research helped build the scaffolding of his nation’s modern public health system.

On the other side of the Atlantic, James McCune Smith would spend much of his career as the physician for the Colored Orphan Asylum in Midtown Manhattan, which was founded in 1836. He worked tirelessly for his young charges, some of whom were dying from measles, smallpox, and tuberculosis. Some of them were there because their parents had died or because they could not take care of them. McCune Smith wrote rigorous research articles debunking phrenology, a pseudoscience that claimed that an individual’s intellectual capacity is determined by the size of their skull, and homeopathy, which he called “the most deadly quackery that curses the nineteenth century.” He died shortly after the end of the Civil War, in November of 1865, three years before the birth of the man who would become his intellectual heir and carry on his legacy of social activism: W.E.B. Du Bois.

When Du Bois began his fieldwork in the shadow of post-Reconstruction America, there was a new and even more virulent strain of racism emerging that perpetuated toxic myths about race under the cloak of science: eugenics. The basic premise of eugenics is that racial and ethnic differences are due to genetic differences—and that undesirable traits like “feeble-mindedness” and poverty were inherited. Society would be better served by “thinning the herd,” a social Darwinist idea that was used as the pretext for barbaric acts like the sterilization of thousands of poor women of color—the so-called “Mississippi Appendectomies”—and was later championed by Adolf Hitler, whose quest to build an Aryan master race led to the extermination of millions of Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, Slavic prisoners of war, and other “undesirables” in the 1940s.

This was the context in which Du Bois began his work. He knew that the only way to combat the ideas of inherent inferiority—ideas that even his seemingly progressive sponsors might hold implicitly—was to use the tools of sociological research to document the conditions of the neighborhood. “My vision was becoming clear,” he wrote in his memoir Dusk of Dawn. “The Negro problem was in my mind a matter of systematic investigation and intelligent understanding. The world was thinking wrong about race, because it did not know. The ultimate evil was stupidity. The cure for it was knowledge based on scientific investigation.”

Despite the fact that he wasn’t given an office or even an academic title, on August 1, 1896, he started work, canvassing door to door for eight hours each day, talking to local residents about their work lives and families. Although he was initially frightened by the rumors of violence that hung in the air, what he discovered surprised him. Even though the ward was poor, it pulsated with life. There were nearly two dozen restaurants and taverns, thirteen grocery stores, a handful of bicycle shops, three bakeries, a hardware and furniture store, and four mortuaries, including two establishments run by women. There were more than a dozen schools in the ward staffed by sixty-four teachers, and about 86 percent of school-age children attended.

The diminutive scientist—he was only 5’6″—cut a striking figure in his dapper three-piece suit, top hat, and cane. Sitting in the parlors, kitchens, and living rooms of his subjects enabled Du Bois to inspect their residences and witness firsthand the reality of their living conditions. Over a three-month period of field research, he spent more than eight hundred hours and spoke with approximately 2,500 households in his investigation. He augmented his research by combing through background materials from Philadelphia libraries—including the private libraries of some of the more well-off locals—finding colonial records, manuscripts, biographies, legal documents, newspaper articles, correspondence, and other publications to corroborate his work.

[DuBois’] vision and execution of a disciplined research plan enabled him to build a holistic and scientific foundation that could upend centuries of structural racism and dehumanization.

His exhaustive research of census data revealed that Black Philadelphians were dying of several common maladies, including pneumonia and tuberculosis, at a rate two times higher than their white neighbors were. The gap in infant and childhood mortality was huge: Black Philadelphians were twice as likely to die before the age of fifteen as their white counterparts. But his greatest achievement was proving that racial differences in health were primarily due to social, not biological factors; they were the inevitable consequence of the “vastly different conditions” of living between whites and Blacks.

Only about one in eight of the dwellings in the Seventh Ward had access to bathrooms and toilets or even hot water, because the area was in an older part of the city that lacked indoor plumbing. Families were often crammed into one room, with four or five people sharing the space, and some were forced to take in itinerant borders, many of them newly arrived from the South, to help defray expenses. Residents did the best they could under difficult circumstances, building outhouses or makeshift latrines in hallways that were shared communally.

While tuberculosis was the leading cause of death for Blacks in Philadelphia, the chief culprits behind the excess death rates were primarily environmental, such as bad ventilation and lack of protection against the dampness and cold. Being forced to live in the most unsanitary places in the city was making Black Philadelphians more vulnerable to highly contagious infectious diseases like tuberculosis, Du Bois noted—not some inherent inferiority. Especially significant is that he found that death rates were higher in the Fifth Ward, “the worst Negro slum in the city and the worst part of the city in respect to sanitation,” he wrote, than in the predominately Black Thirtieth Ward, which had “good houses and clean streets,” a finding that added further weight to the fact that their skin color was not the cause of their poor health.

Even more eye-opening: Du Bois documented that life expectancy for Blacks was between 30 and 32 years in 1900, compared to 49.6 years for whites; poverty, segregation, and lack of access to doctors and health care facilities effectively excluded them from the health-care system. “The most difficult social problem in the matter of Negro health is the peculiar attitude of the nation toward the well-being of the race,” he noted. “There have been few other cases in the history of civilized peoples where human suffering has been viewed with such peculiar indifference.”

Du Bois’s ultimate report was a subversive text because it went far beyond the scope of his original mission, which was simply to provide a quasi-scientific cover for his elite sponsors’ barely concealed contempt and their devious plans to subjugate the residents of the Seventh Ward. His vision and execution of a disciplined research plan enabled him to build a holistic and scientific foundation that could upend centuries of structural racism and dehumanization that robbed marginalized groups of their humanity. He didn’t just chronicle the miserable aspects of the neighborhood, but offered a reason why the houses were so filthy and their lives sometimes chaotic: Whatever was plaguing the community was a symptom of the despair of racism. What makes his beautiful work so powerful, and what is at the heart of it, is that it not only looks at the historical roots of his subjects’ struggles but goes beyond the basics of data science and embraces their deep humanity in all its beauty, culture, possibilities, and messy splendor.

He discovered that these people were hardly down and out. “Behind the veil, you find a city within a city, with its own ecosystems that had different class hierarchies and different occupations, and different educational levels,” said Marcus Hunter, a professor of sociology and African American studies at UCLA. “He felt it would be a disservice to that community to not amplify all its diverse dynamics. Essentially, what he was saying is look at what these people are doing without any resources. Imagine if you actually fulfilled your duty of giving them resources, how they could actually live.”

Du Bois’s groundbreaking work The Philadelphia Negro, which was published in 1899, established his reputation as one of the United States’ premier intellectuals, a voice for “his people,” as commentators would later say. But beyond that, his study is considered a foundational text in the then-nascent field of sociology and statistical research. Du Bois was unflinching in his condemnation of the social forces that created the so-called “Negro Problem.” The poverty, disease, crime, and frail family structure that still hadn’t recovered from centuries of slavery were largely the result of racial prejudice that cut off opportunities, he maintained: “How long can a city teach its black children that the road to success is to have a white face?”

__________________________________

From The Cure for Everything: The Epic Struggle for Public Health and a Radical Vision for Human Thriving by Michelle A. Williams. Copyright © 2026. Available from One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Michelle A. Williams

Michelle A. Williams is a professor of epidemiology and population health at Stanford University School of Medicine and former Dean of the Faculty at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, where she also served as the Angelopoulos Professor in Public Health and International Development and currently holds an adjunct professorship. An internationally renowned epidemiologist and award-winning educator, Dr. Williams is a member of the National Academy of Medicine and the American Epidemiological Society. She has authored more than 550 peer-reviewed research articles and is recognized as a leading voice in public health science and global health.