“She was dead. The step where she used to sit was empty. She was dead.”

Virginia Woolf described the days before her mother’s funeral as a period of “astonishing intensity.” She and her siblings “lived through them in hush, in artificial light. Rooms were shut. People were creeping in and out. People were coming to the door all the time. . . .The hall reeked of flowers. They were piled on the hall table.” It was the spring of 1895 in London, but it may as well have been the winter of 2007 in Boston, a stretch of weeks I remember above all as crepuscular and silent, shot through with the cold beauty of a hundred pounds of flowers and the hollow chiming of the doorbell. I couldn’t shake that crystalline, hyperaware feeling one gets on important occasions—on birthdays, for instance, or on losing one’s virginity. My father is dead, I said to myself, my father is dead. Again and again I said it, and still I failed to grasp what it meant.

The first night I slept badly and at five in the morning got up to use the bathroom; the sky outside was not yet light, and I had the sudden impression that the space around me was thick with ghosts, or rather one ghost, who, gigantic, permeated the whole room. It was an alarming sensation, and I felt it several times before never feeling it again. (On the day after Julia died, Virginia told Stella she had seen an apparition, a man sitting with her mother on the bed. Stella—the daughter of Herbert Duckworth, Julia’s first husband—looked frightened. “It’s nice that she shouldn’t be alone,” she finally said.) Later, on trying to pretend my father could see and hear me from above, I grew exhausted.

The house continued to fill with cards and flowers—death will mobilize even the most distant of relations, it seems. My mother, who loved flowers but worried at the excess, longed for a rationing system that would allot her one bouquet a week instead of 50 all at once. She also saw the ringing doorbell as an interruption at a time when she wanted to be alone with my father. But I liked hearing from the outside world: grief is rapacious, and cards and flowers functioned as its fuel. As long as they continued to proliferate, the experience of loss was active, almost diverting. It was only when their numbers dwindled, then ceased altogether, that a kind of dullish hunger set in.

My mother was resistant, too, to a commemoration of any kind. My father was still alive when she began objecting to a funeral with fierce, panicky resolve, and though he had concurred—and had, at her urging, warned friends who visited the hospital not to expect one (so it became his decree)—I remember thinking that she hadn’t given him much choice. I expect her opposition lay in her inclination for privacy, her possessiveness of his memory, her aversion to public vulnerability; and yet, being vulnerable, she was unable to mount an effective protest when some friends insisted: several weeks after the cremation, we invited 75 people to our house for champagne and orange juice. In anticipation, she made the nearly calamitous decision to try to stall the flowers, moving the bouquets to the living room and turning down the heat. That night, the temperature dropped 40 degrees and the pipes froze; her next day was spent crawling around with a hairdryer, an attempt to prevent the metal from cracking and water from flooding the floor.

But the party went well. Several of my father’s friends gave toasts, and my mother, impressing me with a talent for public speaking, read an excerpt from Edward St. Aubyn’s Never Mind. I hadn’t planned on talking myself, but at the last minute scrawled down a speech about my father and Rhode Island. At its center were words that he had said to me that fall: “I’ve had a damn nice life.” During my mother’s toast I had laughed, but when I tried to give my own, I cried so helplessly that my friend Jessa had to read the first paragraph in my place.

Eventually, that hyper-saturated feeling began to fade. On first returning to my apartment, I had been met by a spectacular flurry of death-related activity. My friends’ parents sent flowers; acquaintances sent cards. Jessa gave me some DVDs of TV shows. Another friend, Laura, an Orthodox Jew, invited me to her parents’ apartment for a kind of mini sitting shiva. For several hours she and her mother listened as I talked about my father’s life; I loved that neither was cowed by death’s awkwardness. After a while, though, the distractions stopped. In their absence, I found grief unsatisfying. There was nothing to cling to. My father is dead, I continued to say, my father is dead. My appetite for wishes had atrophied. I would ignore the clock at 11:11 and unthinkingly flick an eyelash from my cheek—there was not a single thing I wanted.

I drifted through my days with an unfamiliar sense of alterity. I was enrolled in an education class for a new teaching position; I didn’t know the other students, and I remember the dreaminess and alienation with which I sat at the back of the room, watching from my high-up perch—or so it seemed—and saying, over and over again, My father is dead. I spent an absurd amount of time imagining the moment at which various acquaintances had learned of my loss, and I basked in the special haze that now must cling to me (much as Virginia, dreaming she had been diagnosed with a terminal illness, enjoyed what she called “a luxurious dwelling upon my friends [sic] sorrow”). Above all, I disliked the passing of time, disliked the thought that every minute carried me further from my father. This was impossible to reconcile with the feeling of waiting, with the sense that something on the horizon would soon give substance to this stupid vagueness.

Above all, I disliked the passing of time, disliked the thought that every minute carried me further from my father.Virginia described a similar malaise, recalling how the intensity of those first few days gave way to a “muffled dulness that then closed over” her and her family: “we seemed to sit all together cooped up, sad, solemn, unreal, under a haze of heavy emotion. It seemed impossible to break through. It was not merely dull; it was unreal.” She chafed beneath the suffocating mourning conventions espoused by Queen Victoria—the parties ceased; the laughter ceased; for months, the family wore black from head to foot. Even their notecards were ringed with black. Hand in hand, they marched to Kensington Gardens to sit beneath the trees, and once there the silence was oppressive—it was, she said, as if a “finger was laid on our lips.” Leslie Stephen’s groans resounded through the tall, dark house; he paced up and down in the drawing room, exacting pity from Stella and his female children, waving his arms, wailing that he had never told Julia how much he loved her.

At 13, Virginia did not recognize the root of her disquiet; when Thoby, speaking of the dissonance between the siblings’ inward experience and outward behavior, remarked that it was “silly going on like this”—“sobbing, sitting shrouded, he meant”—she was appalled. But in retrospect she saw that he was right. The tragedy of her mother’s death, she said, “was not that it made one, now and then and very intensely, unhappy. It was that it made her unreal; and us solemn, and self-conscious. We were made to act parts that we did not feel; to fumble for words that we did not know. . . . It made one hypocritical and immeshed in the conventions of sorrow.”

I lacked the kinds of elaborate customs that governed the Stephens’ behavior, of course; thanks to my era, and to my father’s hostility to organized religion, I lacked any customs at all. But while I wouldn’t have traded the freedom to mourn as I liked for those claustrophobic, false-feeling Victorian practices, or even the comfort of a god I didn’t believe in—how gratifying, that afternoon of sitting shiva!—I did find myself longing for ritual, for structure, for some organizing principle by which to counter the awful shapelessness of loss. The conventions of sorrow may give rise to hypocrisy, but sorrow uncontained holds its own perils.

*

The beginning of “The Lighthouse” finds Lily sitting alone at the breakfast table, awkwardly wondering whether to pour herself another cup of coffee and struggling to summon the appropriate emotions. “How aimless it was,” she thinks, 44 years old, still unmarried, and returned to the Hebridean house for the first time in a decade. “How chaotic, how unreal . . . Mrs. Ramsay dead; Andrew killed; Prue dead too—repeat it as she might, it roused no feeling in her.” In place of sorrow is her vacant mind; in place of familiarity a morning on which “the link that usually bound things together had been cut.” A family fight is under way—Mr. Ramsay demands a voyage to the lighthouse, but Nancy has forgotten the sandwiches and Cam and James are running late—and to Lily at the table, still straining to make sense of it all, their raised voices are like symbols, which, she thinks, were she only able to string them together, would allow her to get “at the truth of things.” For coupled with the morning’s strangeness is its unnerving incoherence: “The grey-green light on the wall opposite. The empty places. Such were some of the parts, but how bring them together?”

When I first read To the Lighthouse, Lily Briscoe bored and perhaps even repelled me slightly. “Poor Lily,” Mrs. Ramsay calls her privately, thinking of how Mr. Ramsay finds her “skimpy,” and the phrase stuck with me for reasons that no doubt betray a latent sexism—because she is a spinster, because Paul shuns her at dinner, because her “puckered-up” face is less appealing than Mrs. Ramsay’s incomparable beauty or Minta’s golden haze. She seemed an uninspiring substitute for the extraordinary woman we had lost. But there is a fire in Lily, that extraordinary woman tells us, “a thread of something; a flare of something.” And today—15 years have passed—I can at last perceive that fire for myself. Lily is roughly the age that I am now when we first meet her, and it has become curiously easy to see myself in her story—in her conflicted feelings about marriage, in her determination to investigate the vicissitudes of loss. Her fears are those of the 13-year-old girl who stands beside her mother’s corpse, worried at her inability to feel; her frustrations are those of the grown writer who must confront grief’s fogginess, its unreliability. “Why repeat this over and over again?” she thinks angrily of her attempts to register the fact of Mrs. Ramsay’s passing. “Why be always trying to bring up some feeling she had not got?” But it’s Lily’s response to these fears and frustrations, her proposed solution to the question of how to bring together the morning’s inconsonant parts, that makes me like her best of all. Rather than performing her anguish for her hosts, or going through the motions of prayer, or even just heading back to bed, she decides to gather her paints and return to her picture of a decade earlier—to embark upon a true portrait of Mrs. Ramsay, a true portrait of Mrs. Ramsay’s absence.

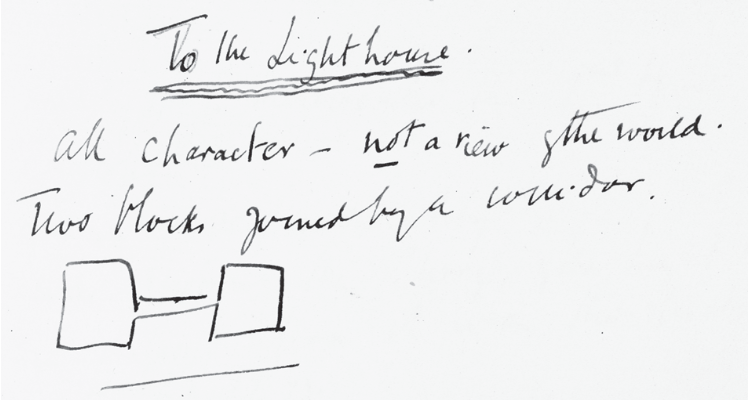

In her original notes for the novel, Woolf envisioned “Two blocks joined by a corridor,” and drew a shape that looked a bit like a dumbbell:

The form would allow her to convey the devastating effects of the Great War, and to communicate the horrific rupture that had put an end to her childhood. It was also how she expressed the similarities between her own project and that of Lily, who wrestles throughout with the aesthetic dilemma of “how to connect this mass on the right hand with that on the left,” and ultimately embraces the central corridor in the book’s final sentences: “With a sudden intensity, as if she saw it clear for a second, she drew a line there, in the centre. It was done; it was finished.” Lily’s grief is a mirror of Virginia’s own, and her painting a surrogate for the novel; both are an attempt to make sense of the death that set their authors’ lives adrift. “Until I was in the forties,” Virginia recalled, “the presence of my mother obsessed me. I could hear her voice, see her, imagine what she would do or say as I went about my day’s doings.”

Lily’s grief is a mirror of Virginia’s own, and her painting a surrogate for the novel; both are an attempt to make sense of the death that set their authors’ lives adrift.The incoherence that so plagues Lily in the Hebrides has its forebear, surely, in the sense of unreality that swallowed up the Stephens as they mourned. But I expect that anyone who has lost anyone is well acquainted with that terrible abstraction—certainly it was the defining feature of my own bereavement. And it felt oddly revelatory when I realized that my favorite book was also contending with that issue; that while the novel offers a clear rejection of the Victoriana that so confined Virginia as a child, it embodies, too, her desire to find a workable replacement for that tradition, her understanding that we all need some structure by which to contain and grapple with our dead. Thus why To the Lighthouse is a novel full of shapes, why Lily struggles to compose her painting, why Woolf poured her family’s story into such a strict, unusual mold. The book’s radical form—not just a pioneering literary innovation—is also an endeavor to speak to and rectify grief’s essential formlessness.

Is it any wonder that in writing my own family’s story, I would choose that structure for myself? Use it to bind the disparate parts, to lay a path toward some sense of resolution? Virginia considered the writing of To the Lighthouse an exorcism: “I wrote the book very quickly; and when it was written, I ceased to be obsessed,” she remembered. “I expressed some very long felt and deeply felt emotion. And in expressing it I explained it and then laid it to rest.”