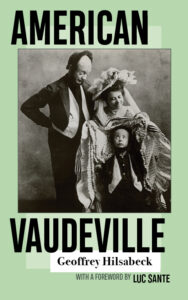

How Vaudeville Told the Story of America… to Americans

Geoffrey Hilsabeck on the Dizzying Dream of This Country’s First Entertainment Industry

For 30 years, from, say, B.F. Keith and E.F. Albee’s first continuous show at the Bijou Theatre in Boston, 1885, to the proliferation of nickelodeons and the opening of the first Hollywood studio in a roadhouse on Sunset Boulevard in the early teens, vaudeville was the most popular form of entertainment in the country. America at the turn of the century was an electric world of widely available shredded wheat, cotton candy, Ferris wheels, and semiautomatic rifles, filing cabinets, and disposable razors.

Then as now people wrung their hands over the meaning of America. To say, finally, what it means. “American history needs a connected and unified account of the progress of civilization across the continent,” wrote the historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1889 in a review of Theodore Roosevelt’s The Winning of the West. Over the next 30 years, vaudeville would answer Turner’s call with parody, sentimentality, racist caricature, virtuosity, slapstick, song and dance, and anarchy. It would tell the story of America to America, with a clown playing the president in motley, on a donkey instead of a horse, illuminated by electric lights rather than the star-spangled western night.

*

Vaudeville emerged from the chaos of the 19th century—the time of my great-grandfather’s great-grandfathers and grandfathers and father—inherited its habits and prejudices, and added a few of its own. It rose from the bed of the 19th century like a clerk getting ready for work in his bachelor flat, still wet with dreamsweat. The strange dream of the Eclectic Remedy Co., a man selling infant soothers laced with opium and tonics made of red pepper and turpentine. The strange, unruly dream of the circus, which Emily Dickinson watched pass from her bedroom window and days later could “still feel the red in [her] mind.” A dream of emerging markets. Of unfixed address. A disquieting, erotic dream of tableaux vivants—“The Greek Slave,” “Venus Rising from the Sea,” “Suzanne in the Bath”—dream of speeches, conventions, nominations, camp meetings, singing families. Of minstrel shows. A dream of wires, a gathering of wires. A terrifying dream of Barnum’s American Museum burning down and with it two whales, an elephant, wax figures of Christ and his disciples, an electric eel, monkeys, big and little monkeys, young, old, and middle-aged monkeys, happy monkeys, sad monkeys, monkeys that fought with each other and were beaten by the Management for it.

The minstrel show, the circus, melodrama, dime museums, medicine and boat shows, and local stuff, too, political speeches and parades, song-and-dance performances at temperance societies, sermons, these are the sources of vaudeville, the lakes that make up the tablelands, the rivers that feed the mighty Mississippi: the Missouri, the Ohio, the Wabash, and the Tennessee. They throw their waters south to the Gulf of Mexico, warm as a bath, warm as the silver bath in which images are fixed.

At the Ramona, East Grand Rapids, MI: Erz Herzog Joseph’s Gypsy Band. Herr Holtum catching a cannonball. The Three Richards and the Lunatic Bakers. Annie Hart’s Rough Riders with Charles E. Grapewin and Anna Chance. El Cato plays Bach and Liszt on a xylophone. Xylophone and accordion. Guitar and ukulele. The whistler Charles Mildare. Snare drums and banjos, banjos to animate sand jigs and clog dancing, a gold banjo set with jewels. After a few bars on the banjo, John Carl would stop suddenly to recite Shakespeare, both straight and in burlesque, what were known as “Bughouse Hamlets.” Carl was always associated with a song called “The Lively Flea”:

Feeding where no life may be,

A dainty old chap is the lively flea.

Feeding where no life may be,

A dainty old chap is the lively flea.

At Coney Island’s Dreamland: “Music and Fun in a Butcher Shop.” “A Blue Grass Widow.” Rousby’s Electrical Novelty. The monologist Clifton Crawford, his hair whitened, sings with a squeaky voice and then recites “Charge of the Light Brigade.” Max Waldon doing 14 minutes of female impersonation. The Metropolitan Quartet belts out arias. Byers and Hermann in pantomime with one doing contortion work—or Ferreros, the musical clown with an educated dog—or Chalk Saunders with his well-known “Physgogs”—or W. C. Fields, Amerous Werner, Friscarry. “The Frog’s Paradise.” Prelle’s Talking Dogs. Holdin’s Mannikins, the Great Sandor Trio. The Two Vivians are sharpshooters. Thomas Edison’s Vitascope.

Vaudeville told the story of America to America, with a clown playing the president in motley, on a donkey instead of a horse, illuminated by electric lights rather than the star-spangled western night.As early as 1896, movies became a regular part of many vaudeville shows. They were known as “the flickers” and often placed at the end of the bill in a spot traditionally reserved for dumb acts and visual novelties. Edison liked to buy up old locomotives and stage train collisions to film. Flickering celebrities, local actualities. “The Gardener and the Bad Boy.” The projector was as much of an attraction as the images it projected, which might include the surf breaking on a stretch of beach; a boxing match between a tall, thin man and a short, fat one; a few seconds of a popular farce repeated over and over. Any sense of diminishment the audience might have felt at seeing these performers made two-dimensional was replaced by their sense of wonder at the technology by which they were so reduced, the black magic used to trap them in this strange machine, a woodland creature speaking light with a box of a body set on four spindly legs.

Aristotle identified the sphere as the perfect shape. Vaudeville was, like me, all lines. Two men juggled standing on unsupported ladders. The Tom-Jack Trio threw snowballs at triangles. Amateurs and experts, apprentices and journeymen graced its stages, Eva Tanguay and Bert Williams but also a hypnotist named Ahrensmeyer. Nobodies, wannabes, hangers-on: the archive is full of them, its folders and boxes minor monuments to people who, but for a few scraps of paper preserved in plastic, grouped and catalogued, left no trace on this earth. Small talents, forgotten acts. Jacks-in-the-pew. Many likely died in poverty and all in relative obscurity. They tried. And mostly they failed. Mostly they knew loneliness, the loneliness of nothing theaters in nowhere towns, like the theater below a bowling alley in Lancaster, PA, or the theater in Ohio that wasn’t actually a theater but a butcher shop. They knew disappointment when their act fell flat and they weren’t asked back. They knew sweaty desperation.

The Great, the Marvelous Carlosa, the World’s Greatest Ladder Balancer. She wrote to her booking agent from Springfield, MA, October 1898, looking for work. “D. Sirs, I have all time open after November 7th. Different from the rest so everybody says.” The DeBeaumonts were dancing magicians. They brought Merry Moments of Modern Magic, Mirth, and Mystery. They wrote en route. “My dear Sir: You will doubtless remember the writer . . .” When William James said that all the human heart wants is a chance, surely he had the DeBeaumonts in mind, or poor Joe Allen, bitter, hungry Joe Allen, stranded in Petoskey, MI, with no money to get home to his wife because his act had been scrapped by the manager of the Robbins Little Trixie Co. A tramp juggler who can’t juggle—a vaudevillian without vaudeville—a skipping stone that stopped believing in itself halfway across the glistening river Is.

“Dear Sirs.—,” writes Ms. Helen N. Bovee, the World’s Greatest Lady Hypnotist, “Have you completed your list of attractions for Lyceum Entertainments for the coming season? If not,—how would a good lecture on Hypnotism, Mesmerism, and Kindred Subjects, illustrated with live good subjects, to be used in cataleptic posing; (2) holding up of three heavy men on body while suspended by heels and neck; (3) sewing lip by needle and thread without pain or loss of blood; (4) up to date mind-reading lists,—take with you and your patrons?”

“There is a crack in everything God has made,” said Emerson. The vaudevillian was proof of that. Itinerant, tribal, superstitious, she carried her belongings in a trunk with separate compartments for her shoes, her iron, her washcloths and sponges and soap. It was bad luck to whistle in your dressing room or to throw away your dancing shoes, and woe to the performer who saw a bird land on her windowsill. Her life was filled with risk, skirted by failure, a freelance performer always begging for work. What was it like to hop on stage and play for a crowded hall or to scattered applause? How did rehearsal feel, especially the solo performers practicing their acts in giant, silent privacy, a privacy so giant and silent that planets must have spun through it? The Great Thurston. The Great Larry Leroy. The Great Koppe. Each greedy for the song of the I-singer. Come, Koppe, deliver your “excruciatingly funny monologue.” You are “the Only,” “the Original,” a good egg with a good, yellow heart but no star, sadly. A hack, a sad sack, at best a Bottom. You were touched once in a dream by a goddess and could never shake the feeling. You spent your life chasing it. Your permanent address was a newspaper office.

______________________________________

Excerpted from American Vaudeville by Geoffrey Hilsabeck. Excerpted with the permission of West Virginia University Press. Copyright © 2021 by Geoffrey Hilsabeck.