How Ulysses Was Almost Banned By the State of New York

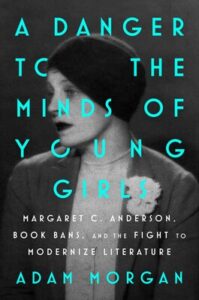

Adam Morgan on Margaret C. Anderson and the Early Fight Against Literary Censorship in America

On a cold afternoon in the heart of Greenwich Village, Margaret C. Anderson bumped into the man who wanted to put her in prison.

The streets of New York were lined with snowdrifts stained black by soot, smog, and Model T motor oil. Downtown, the terra-cotta-clad Woolworth Building was the tallest in the world while the Jazz Age simmered in speakeasies like The Back of Ratner’s. Uptown, Langston Hughes was a freshman at Columbia University, publishing poems in the school paper. Across the city, neighborhoods were consumed by the first Red Scare following a presumed anarchist bombing on Wall Street the previous year that had claimed the lives of thirty people.

Margaret braced herself against the chill in the one suit she owned, eggshell blue, worn daily with a georgette blouse that she washed every other night by hand. Walking down Eighth Street, she began editing Greenwich Village in her mind: flower boxes for every window, granite cobblestones instead of brick for the pavement, red maples and golden ginkgos to replace the oaks. “I always edit everything,” she wrote. “…I edit people’s clothes. I edit people’s tones of voice, their laughter, their words. It is this incessant, unavoidable observation, this need to distinguish and impose, that has made me an editor.”

Sumner thought Margaret was a beautiful but misguided bohemian; by now, he knew what she truly was.

But she couldn’t edit the man coming her way in a dark three-piece suit: John Saxton Sumner, secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Margaret recognized him at once. At forty-four years old, he was already the most notorious censor in America. Like his NYSSV predecessor, Anthony Comstock, Sumner had ordered the burning or helped to bring about the suppression of thousands of books and other publications deemed obscene by the standards of the Young Men’s Christian Association—including Theodore Dreiser’s The Genius, a semiautobiographical study of male and female libido, and Margaret Sanger’s sixteen-page pamphlet “Family Limitation,” which explained six different contraceptive methods.

On October 4, 1920, Sumner had had Anderson arrested and charged with a felony that could send her to prison for up to five years. Her crime? Publishing a “filthy, indecent, and disgusting” work of fiction in her literary magazine, The Little Review, and distributing copies through the Post Office Department (later replaced by the US Postal Service). For the last two years, Margaret had been serializing an experimental novel that would shake the foundations of literature and demolish the cultural status quo on both sides of the Atlantic: James Joyce’s Ulysses.

In the winter of 1921, when she crossed paths with Sumner on Eighth Street, Margaret’s trial was only a few weeks away. For Sumner, the publication and distribution of Ulysses was a clear violation of the Comstock Act of 1873, which made it illegal to mail any “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” materials “from any post office or by any letter carrier.”

When their argument turned into a shouting match, Margaret suggested that they continue the conversation in the Washington Square Bookshop, just a few floors beneath her apartment at 27 West Eighth Street. When he began his investigation, Sumner thought Margaret was a beautiful but misguided bohemian; by now, he knew what she truly was—a politically radical lesbian who wrote some of the earliest defenses of homosexuality and birth control in the United States.

Inside the bookshop, Sumner told Margaret that Ulysses was so obscene that it was “wholly conceivable that the reading of the [novel] by a young woman could be very harmful.”

“Mr. Sumner, that is an ineptitude,” Margaret said. “There is no thinking in that kind of remark.”

The censorship of American books, magazines, and other literature dates from the Puritan government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the first book ban in United States history: Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan in 1637, which criticized the colony’s violence against Native Americans. By the turn of the twentieth century, book censorship had become a battlefield in America’s first modern culture war. On one side, Margaret and the experimental writers she published wanted to break free from the limitations that had constrained art and create something new. On the other side, government officials and their proxies wanted to destroy any printed material they believed could corrupt the minds of young people: writings about sex, homosexuality, and birth control.

Margaret’s criminal trial for publishing Ulysses would be a crucial turning point in the battle between censorship and free expression.

The Red Scare made Americans paranoid that anyone they passed on the street could be a bomb-wielding anarchist, and Comstock and Sumner’s book-banning campaigns stoked fear that reading modern fiction and poetry could turn young women into disease-ridden lesbians and prostitutes. US Senator (and former South Carolina governor) Coleman Livingston Blease said in 1930 that he was ready to “see the democratic and republican form of government forever destroyed if necessary to protect the virtue of the womanhood of America.” As a result of this moral panic, the decades between World War I and World War II were some of the most tightly controlled years in the history of law and literature—and Margaret’s criminal trial for publishing Ulysses would be a crucial turning point in the battle between censorship and free expression.

Inside the Washington Square Bookshop that winter afternoon, Margaret felt sorry for Sumner. “I was embarrassed by the antipathy with which everyone in the bookshop regarded him. He was probably hurt by it,” she wrote. She recognized Sumner’s charm, and as they spoke he attempted to prove his bona fides—that he was a reader and admirer of fiction. But when he quoted Victor Hugo and others she considered “second-rate minds,” Margaret realized that she had stumbled upon “the perfect enemy” for her trial on February 21, 1921.

This trial would make Ulysses the most influential literary work of the twentieth century. It would change the very definition of what a book could be. But Margaret’s fate would be far stranger, and mostly forgotten. Her story is a tale of three cities—Chicago, New York, and Paris—at the height of their cultural renaissances; of provoking the FBI into compiling a dossier the agency still refuses to make public; of mercurial love affairs with some of the most glamorous and intelligent women in the world; of frequent ecstasies and rare brushes with self-harm. She shared meals with Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Marcel Duchamp, Frank Lloyd Wright, Man Ray, and Pablo Picasso. She lived in abandoned castles and a dead lighthouse in the ancient forests of France; under the thirteenth-century monastery roof of a cult; and in the circle of a world-renowned mystic. She held secret meetings in a Left Bank apartment with like-minded women whose writings, like Joyce’s Ulysses, would be both censored and responsible for changing literature—and the way we talk about it—for the next one hundred years.

__________________________________

From A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls: Margaret C. Anderson, Book Bans, and the Fight to Modernize Literature by Adam Morgan. Copyright © 2025. Published by Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Adam Morgan

Adam Morgan is a culture journalist and critic who lives near Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His writing regularly appears in Esquire, and has also been published in The Paris Review, Scientific American, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, and more. He spent a decade in Chicago, during which time he founded the Chicago Review of Books and covered the city’s arts and culture for Chicago magazine and the Chicago Reader.