How Truman Capote Was Destroyed by His Own Masterpiece

Inside a New Volume Reproducing the Original Manuscript

of In Cold Blood

It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends.

The success was all encompassing, but the cost would prove greater than even Capote had realized. Having read an article in the New York Times about the brutal slaying of a family at their farmhouse in Kansas, Capote embarked on a journey to the small rural farming town. Holcomb, located in Southwest Kansas, was a town of just under three hundred people and quintessential 1950s America. A small tight knit community that felt and acted more like one large family than a municipality.

Needless to say, the murders of prominent farmer Herbert Clutter, his wife Bonnie, their youngest daughter Nancy and their son Kenyon, sent shockwaves through the town. Not only was this kind of crime unheard of in Holcomb, it also cast a cloud of suspicion over the entire town. Who would have had reason to kill the Clutters? And even if there had been cause to kill Mr. Clutter, how could anyone justify killing young Nancy and sweet Kenyon? Neighbors locked their doors and kept their children home from school, firearms were placed next to bedside tables, and all were on high alert for fear that they were next on an unknown killers hit list.

It is amidst this air of fear and dread that Truman Capote arrived in Holcomb in 1959. The town had never seen anything like Capote. A man of diminutive stature, great flamboyance of style and a uniquely high-pitched vocal quality, he was a character that the townspeople could never have dreamed up. But there he was, with his notebook in hand, getting the story. It took time for the community to warm to Truman. Their inherent unease with outsiders was immediately on display, not to mention their added skepticism around a New York City reporter’s arrival in town. But Capote did what he was consistently able to do throughout his life—he charmed them into being on his side.

Capote’s charm offensive was especially targeted toward Alvin “Al” Dewey and his wife Marie. Dewey was the special agent from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, assigned as the Chief Investigator of the Clutter murders. Known as an honest, dedicated and earnest public servant, Dewey was a member of the Holcomb community and knew the Clutters socially from church.

Capote, being both a journalist and sharp social observer, knew that Dewey was the key that could unlock all the access that he needed. His charm offensive on the couple ranged from dinner at their home, where he regaled them with stories of his celebrity friends in New York and Los Angeles, to invitations for them to come and visit him around the world. Before long a bond had been forged (one which would last the rest of Capote’s life) and Truman had the access he needed to begin investigating and writing his story.

Truman now had entrée not only to the details of the investigation, but also to the townspeople who felt he was safe to speak with, given that he had the confidence of Chief Investigator Dewey. Soon Truman was interviewing everyone, from the late Nancy Clutters boyfriend to members of the investigative team. He was given access to files and tips that had pointed the investigators in divergent directions. He had the inside track on how the investigation was progressing.

By December 1959, the search for the killers had run hot, cold and hot again. The investigators had a tip from a prison inmate that seemed credible. Chief Dewey and the investigators followed the lead and headed to Las Vegas where it was believed the perpetrators were. On December 30th, 1959, Perry Smith and Richard Hickock were arrested in Las Vegas and charged with the murders of Herbert, Bonnie, Nancy and Kenyon Clutter. They were promptly transferred from Las Vegas to Kansas where the trial would soon begin. Chief Investigator Alvin Dewey’s arrival back in Holcomb with Smith and Hickock was a triumphant return, as he had successfully tracked down the two men, but it was the end of innocence for the small town.

Would the townspeople come together in solemn remembrance of their slain brethren, or would they jeer at and riot around those who had killed them? The sentiments of the town and the people were all on display and Capote was there to witness and transcribe each and every breath of contradiction.

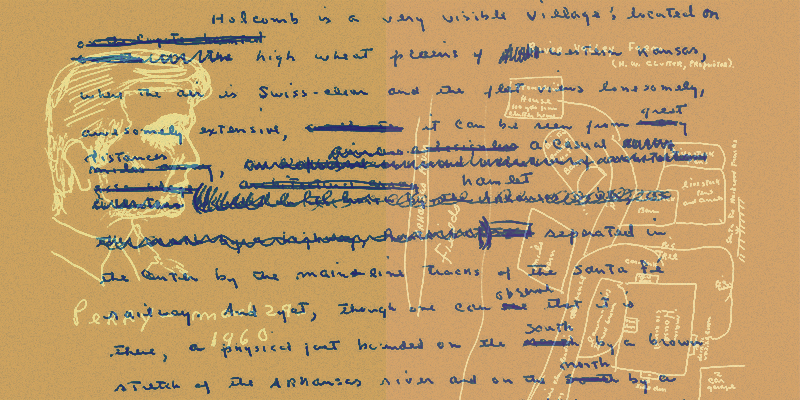

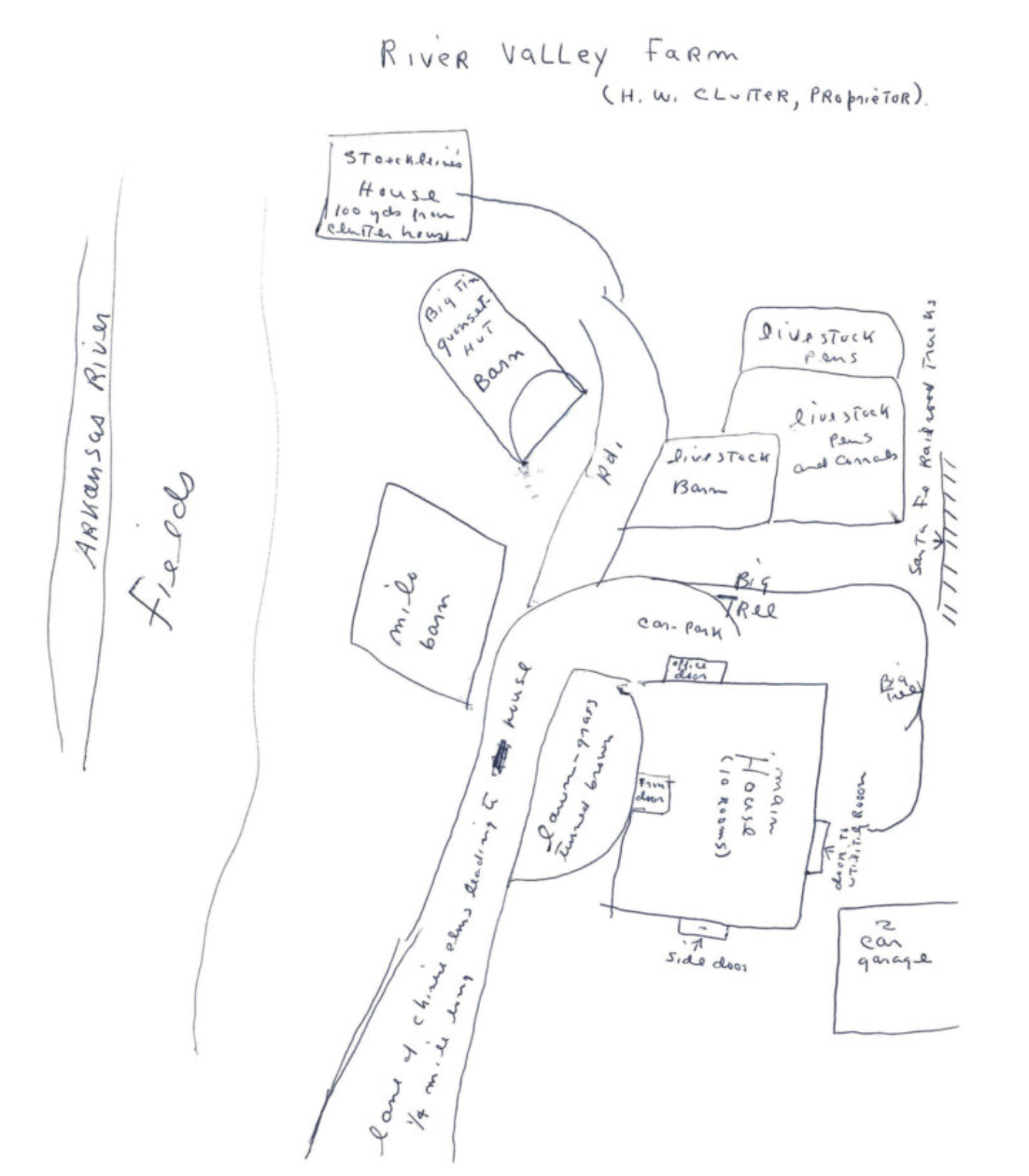

Capote’s sketches of River Valley Farm, the Clutter family home in which the crime was committed. ©Truman Capote Estate. The New York Public Library; Manuscripts and Archives Division (Truman Capote Papers, MssCol 469. Box 7-8).

Capote’s sketches of River Valley Farm, the Clutter family home in which the crime was committed. ©Truman Capote Estate. The New York Public Library; Manuscripts and Archives Division (Truman Capote Papers, MssCol 469. Box 7-8).

Perry Smith and John Hickock were now the objects of Capote’s investigative desire. His story was their story, and he had to once again turn on his charm offensive. While he spoke and communicated extensively with both men, it was Perry Smith who Capote developed a particularly close relationship with. Capote’s obsession seemingly straddled from the physical to the psychological. In Perry he saw the person he might have become had his life taken a different path.

Both men were from homes torn apart and both were eventually orphaned. Truman, ever the intellectual and the aesthete, found in Perry a gentle soul with an artistic nature and intellectual curiosity. They traded books and stories and letters. Their connection became one in which Capote could not fully separate himself from his subject, so as the months turned into years, the relationship became increasingly interdependent.

The years between 1959 and 1965 were filled with Capote communicating with the community at large, the investigators and of course the inmates. Trials came and went, and despite confessions from both men, the wheels of justice turned slowly. By 1965, Truman had finished his manuscript except for the ending. And the ending he needed, the ending he felt his story deserved was a complete resolution for the crimes committed, and that meant death to Smith and Hickock.

As they went through additional motions and hearings, Capote became agitated. His book was ready and after five years, he needed his ending to arrive. Court antics and filings could only continue to delay what he needed, and his fear was always rising that they might receive a stay of execution, in essence leaving him with no ending at all. Yet throughout this entire process, Capote had not fully realized the relationship that had developed between him and the killers, particularly Perry Smith. So, as he waited anxiously for their death, he had not fully assessed what the loss would be for him personally.

Eventually there were no more legal motions filed, no stays of execution from the governor. The future for Hickock and Smith was the gallows. And Capote had his ending. He knew he had to see the story through to its most final conclusion, which meant being there as the executioner placed the sacks over the heads of the two young men, as they were dropped from the gallows, and as the last moments of life twitched out of their bodies. Capote watched in tears and was inconsolable on the plane ride back to Manhattan. His friends rallied around him, but each acknowledged that something in Truman had died with Perry. A small, unidentifiable element of himself had been ripped away.

The success of In Cold Blood was instant and it bestowed upon Truman all the riches he had dreamed. His five years of work had created a new genre of literature, the nonfiction novel, as he declared it. Soon after publication he gave his storied Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in New York. He was the toast of jet set society, and the guests who came to fête him were world leaders, royalty, film stars and of course Alvin and Marie Dewey and a few friends from Holcomb Kansas. 1965 was to be the best year for Capote as he ascended to the global stage as the “It” author and personality of his generation; but something eerie lurked just below the surface.

When I began work on my documentary The Capote Tapes, I was initially drawn to Truman’s years following the publication of In Cold Blood; but I quickly realized that I could never tell Truman’s story without telling the story of In Cold Blood. His story is intrinsically wrapped in Perry’s story. And the sorrow he felt at the loss of Perry’s life and yet the realization that his success was dependent on that life coming to an end, always lingered for Truman. As glamorous as his life was, the years following 1965 and Perry’s death became a slow and long decline into alcohol and drug addiction.

As a young boy in the American South, I grew up reading Capote, from the short stories to the novels. He was an aspirational figure. Someone who lived a grand far away life, he was both indulgent and intellectual. He stood out as an openly gay man when the laws of the land deemed it criminal, but he chafed at the idea of being defined by his sexuality. He was a media personality who emitted wit and charm, but he could also be cruel and inhumane. He was a ball of contradictions. But perhaps most important of all, was his writing. It remains for me so close to home, so near the smells and sounds of the South, so rich in tone and elegant in prose. As Norman Mailer said, “He wrote the best sentences.”

My exploration into Capote’s life was through the lens of never heard interviews that Capote’s friends had given the author George Plimpton. Plimpton had turned those interviews into his oral history on Capote. The tapes are a rich history not simply of Truman, but of the era in which he lived and the range of people he charmed and alienated along the way. Additionally, I spent hours poring over Capote’s notebooks and correspondence. Immersing myself in his detailed penmanship, concise and often witty observations, and the pure genius that is his writing.

Having access to these incredible notes and drafts, was essential in allowing me to further dive into Capote the man, as well as the author. Capote’s literature remains ever more relevant today. From Breakfast at Tiffany’s and the stories of young people running from their past to make a new life in New York, to the True Crime genre which he is undoubtedly the godfather of following his writing of In Cold Blood. Capote’s talent—his unyielding talent—is what continues to make him a captivating personality and author. He wrote it best himself in Music for Chameleons, “But I’m not a saint yet. I’m an alcoholic. I’m a drug addict. I’m homosexual. I’m a genius.”

_____________________

From the introduction by Ebs Burnough to In Cold Blood, the manuscript by Truman Capote, copyright ©2023 by Ebs Burnough and SP Books. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, SP Books. All rights reserved.