How Traveling Booksellers Spread Literature Throughout Ancient Greece

Irene Vallejo on Publishing and Distribution in Antiquity

How many books were there in the golden age of ancient Greece? What percentage of the population could read them? We have only shreds of information preserved by chance, blades of grass that float along on the breeze but don’t allow us to calculate the size of the meadow from which they came. And most of them refer to an exceptional place, the city of Athens. The rest remains in shadow.

Seeking traces of this invisible literacy, we turn to images of readers represented in ceramic paintings. From 490 BC on, there are red-figure urns and vases decorated with scenes of children learning to read and write at school, or people sitting in chairs, reading a papyrus unfurled in their laps. Often the artist traces enlarged letters or words on the scrolls he draws, in such great detail that they can be read—verses by Homer or Sappho.

In almost all cases, the book contains poetry. There is also a mythology textbook. What’s most striking is that the usual protagonists of these small scenes are women, but, paradoxically, in the school scenes girls never appear. This contradiction leaves us with an unsolved mystery. Perhaps these women readers belonged to noble families and were educated at home, or perhaps it was simply more of a motif than a daily reality. We’ll never know.

How must it have been for those merchants Aristotle mentions, among the sun-drenched olive groves, when books were young and everything was happening for the first time?

A gravestone dating from between 430 and 420 BC shows a young man sculpted in profile, absorbed in the words on a papyrus unrolled across his knees, head tilted slightly to one side, his ankles crossed, in exactly the position in which I am writing now. Beneath the carving that gives the chair its shape, we see an eroded lump of stone that looks like a dog sheltering underneath it. The carving depicts the calm of hours spent among books. That deceased Athenian was so enamored of reading that he took it with him to his grave.

At the cusp of the fifth and fourth centuries BC, some characters begin to appear who had until then been unknown: booksellers. It’s in this period that the new word bybliopólai (“sellers of books”) first features in texts by Athenian comic poets. According to them, stands selling literary scrolls would be set up in the agora, among the others offering garlic, vegetables, incense, and perfume. For a drachma, Socrates says in one of Plato’s dialogues, anyone could buy a philosophical treatise at the market. It’s surprising that books were readily available so soon, and in the case of difficult philosophical works, even more so. Judging by their low price, they must have been small or secondhand.

We know little about the prices of books. The cost of papyrus scrolls suggests that the standard fluctuated between two and four drachmas per copy—the equivalent of somewhere between one and six days’ work. The high figures mentioned for rare editions—Lucian of Samosata speaks of a book that cost around seven hundred and fifty drachmas—are no indication of the normal prices of ordinary books. For the prosperous classes, even on the more modest rungs, books were a relatively accessible product.

At the end of the fifth century BC, the age-old tradition of mocking bookworms began, whose archetype would later be Don Quixote. Aristophanes, slyly welcoming intertextuality, makes fun of writers who “squeeze their works out of other books.” Another author of comedies used a private library as a setting for one of his scenes. In it, a teacher proudly shows the famous hero Heracles his shelves stuffed with books by Homer, Hesiod, the tragedians, and the historians: “Take any book you like and read it; take your time, look at the titles.” Heracles, who in Greek comedies is always depicted as a glutton, chooses a recipe book. We know that in those days, instruction manuals on a wide range of subjects circulated to satisfy readers’ curiosity, and among them, the manual par excellence, was a recipe book by a fashionable Sicilian chef.

Athenian booksellers also had overseas customers, and thus the exportation of books began. The rest of the Greek world sought out literature created in Athens, especially librettos of tragedies, the great spectacle of the period. Attic theater captivated even those who loathed Athenian imperialism, as is the case with the powerful film industry of the United States. Xenophon, writing in the first half of the fourth century BC, tells that on the dangerous coast of Salmydessus in today’s Turkey, he found a shoreline scattered with the debris of shipwrecks. Among the wreckage were “beds, small boxes, many books, and other things merchants usually transport in wooden boxes.”

It’s surprising that books were readily available so soon, and in the case of difficult philosophical works, even more so.

There must have been a certain amount of organization to stock the market with books, and people who ran the workshops where they were copied. But we have no clues to tell us how they worked or what the breadth of their reach was, so we are forced to enter the shaky terrain of conjecture. Surely the workshops would copy books with the permission of authors, who wished for a wider readership than their own circle of friends. But they also reproduced texts without consulting their creators. There was no such thing as copyright in ancient times.

One disciple of Plato’s had copies made of his master’s work and set out for Sicily to sell them. He was shrewd enough to guess that there would be a market for the Socratic dialogues there. His contemporaries give the impression that his sales initiative earned him an abysmal reputation in Athens, not for stealing his master’s intellectual property, but rather for getting involved in business at all. This was considered thoroughly plebeian and improper for a man from a good family, especially one who belonged to Plato’s circle.

The Platonic Academy undoubtedly had a library of its own, but the collection at the Lyceum of Aristotle must have surpassed all its predecessors by far. Strabo says that Aristotle was, “as far as we know, the first to collect books.” It’s said that Aristotle bought all the scrolls owned by another philosopher for the immense sum of three talents (eighteen thousand drachmas). I imagine him amassing essential texts for years, spanning the entire spectrum of the arts and sciences of the era, as his money gradually trickled away. Without reading constantly, he would never have been able to write what he wrote.

A small corner of Europe was beginning to be consumed by book fever.

*

Aristotle speaks of tragedians who wrote more for readers than for theater audiences. He adds that their books enjoy “wide circulation.” What might a wide circulation have meant in those early days?

Another statement attributed to Aristotle reveals a world we haven’t yet glimpsed. According to him, booksellers hauled great mountains of books around in carts. Perhaps he is referring to peddlers who took to the open road, clattering from village to village, loaded with literature.

In fact, as Jorge Carrión points out, bookstores with fixed locations are a modern anomaly in a mainly nomadic and poetic tradition. It was travelers who fed the Library of Alexandria with manuscripts; merchants of paper and ink who rolled ideas down the Silk Road as if they were wheels; roving salesmen of used books—among other goods—who set up at inns and fairs as recently as yesterday, having traveled great distances laden with chests, cumbersome boxes, and portable market stands. Today, depending on the geography, mobile libraries on buses or “biblioburros”—book donkeys—keep the old custom of globe-trotting books alive.

Parnassus on Wheels by Christopher Morley describes that nomadic existence. In the United States of the 1920s, Mr. Mifflin travels through rural America in a strange carriage that looks like a tram, pulled by a white horse. When he lifts the vehicle’s side panels, the long wagon turns out to be a book stand with shelf after shelf stuffed with books. Inside, there is no lack of comfort or convenience: an oil stove, a folding table, a pallet to sleep on, a wicker chair, and geraniums on the little window ledges.

Today, depending on the geography, mobile libraries on buses or “biblioburros”—book donkeys—keep the old custom of globe-trotting books alive.

For years, Mifflin had worked as a teacher, “plugging away in a country school…on a starvation salary.” His poor health leads him to move to the country. He builds his cart with his own hands, names it Parnassus on Wheels, and buys a large number of books in a secondhand store in Baltimore. Though he has no lack of cunning and a salesman’s gift of the gab, Mifflin considers himself a roving preacher, called upon to spread the gospel of good books. He drags his cart from farm to farm, along dusty roads shared by wooden wagons and the earliest mass-produced automobiles.

When he arrives at the home of some country folk, he jumps down from his driver’s seat, crosses the yard full of hens scratching in the dirt, and does his best to convince a woman peeling potatoes of the importance of reading. He attempts to convert farmers to his zealous creed: “When you sell a man a book you don’t sell him just twelve ounces of paper and ink and glue—you sell him a whole new life. Love and friendship and humor and ships at sea by night—there’s all heaven and earth in a book, a real book I mean. Jiminy! If I were the baker or the butcher or the broom huckster, people would run to the gate when I came by—just waiting for my stuff. And here I go loaded with everlasting salvation—yes, ma’am, salvation for their little, stunted minds—and it’s hard to make ’em see it.”

These people with weathered skin and frostbitten hands have never had the chance to buy a work of literature, much less to have anyone explain its importance to them. Mifflin discovers that the deeper into the countryside he goes, the fewer books are to be seen and the worse those he does find are. With his singular eloquence, he proclaims that it would take an army of booksellers like him, willing to visit workers in person, tell their children stories, speak to the teachers in their tiny schools, and put pressure on the editors of agricultural magazines until books circulate through the country’s veins and the holy grail reaches the remote farms of Maine.

If this was the situation in the United States in the early twentieth century, how must it have been for those merchants Aristotle mentions, among the sun-drenched olive groves, when books were young and everything was happening for the first time?

_____________________________________

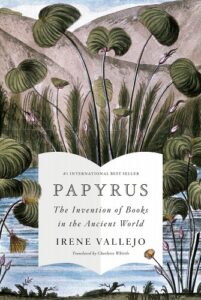

Excerpted from Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World by Irene Vallejo, translated by Charlotte Whittle. Copyright © 2022. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Irene Vallejo

Irene Vallejo earned her doctorate from the Universities of Zaragoza and Florence. Papyrus was awarded the National Essay Prize and the Critical Eye Prize for Narrative in Spain, and it will be published in thirty countries. Vallejo is a regular columnist for El País and Heraldo de Aragón, and she is the author of two novels, three collections of essays, articles, and short fiction, and two children’s books.