How to Write an Obituary For Your Mother

Jenny Qi on the Limits of Language in the Face of Tragedy

I did not know how to write an obituary when my mother died. I was all of nineteen, and the only deaths I’d reckoned with up to that point were those of her parents—whom I’d met only once as an infant—and those of my pet guinea pigs. But my father tasked me with writing my mother’s obituary because I was born and raised in America, and what were my English skills for if not to be my parents’ voice when they needed it. Besides, now that she was gone, it was time for me to be a proper adult. Though I seem to have erased all but the most traumatic memories surrounding her death, I think I Googled obituaries, and I probably followed a simple template. I did not understand that I could do anything else.

Now, years later, I am haunted by the impersonal nature and sheer brevity of my mother’s obituary in the Las Vegas Review Journal. Every time I read an obituary online or a news story about a tragic death or even the inscription of a memorial bench, all of which I do more often than is perhaps normal, I pause to wonder about the deceased and who is left to remember them. Then I feel guilt for the paucity of ways I’ve offered the world to wonder about my mother. In the intervening years, I have looked up guides on writing obituaries and guides on Chinese funeral traditions and read countless books and essays about other people’s losses. I have written a hundred elegies and now a whole book about my mother, my grief, and it doesn’t feel like enough. I have fantasized during late-night anxiety-spiral ruminations about hacking into the Review Journal and replacing that terrible stilted obituary with anything else because I can’t bear the thought of people looking up or stumbling upon Lisa Yu and learning only that she was a casino dealer and writer who passed away on February 23, 2011.

What I want people to read is that on February 23, 2011, Lisa Zhihong Yu, beloved wife and mother to one daughter and two books, passed away at the age of 54. Lisa was born in Nantong in the Jiangsu Province of China—officially her birthday was listed as December 10, 1956, but we are unsure of the exact date because it was recorded using the lunar calendar. She was adopted by a school teacher and a housewife with bound feet; the couple had one biological son but loved her as their own. The Chinese Cultural Revolution interrupted her childhood, and she was sent to a reeducation camp to work in the fields. After returning from the countryside, she finished school and became a history teacher. She married Hansheng Qi, they immigrated to the United States, and they had one daughter, Jenny. In the U.S. Lisa had many different kinds of jobs, including lab technician, real estate receptionist, restaurant manager, and casino dealer. She was a member of the Las Vegas Chinese Writers Association and wrote two books at the end of her life, a memoir honoring her adopted parents published in China and an unpublished semi-autobiographical novel about immigrating to the U.S.

Lisa chose her English name because Americans couldn’t pronounce her Chinese name Zhihong 志红, which translates roughly to “red determination,” an apt description of how she lived her life. She was ambitious and determined above all, and when she chose to do something, regardless of how much she liked it, she did it well. When she returned from the country, she sped through her schooling in half the time allotted, eager to reclaim the life that had been taken from her. Sometimes, this ambition translated into impatience and a sharp tongue. She did not suffer fools. She loved to read from a young age, hiding under the covers with a light to finish novels late into the night. Her favorite book was Dream of the Red Chamber. When she was learning English, she read all the classics, and her favorites included Jane Eyre, Little Women, Les Miserables, Gone with the Wind, and Tess of the d’Ubervilles. Not surprisingly, she loved stories of women who persevered. People were drawn to Lisa’s liveliness and humor, and she picked up lifelong friends everywhere she went. She also had a strong sense of compassion and responsibility for one’s family and community. She saved the best of everything for everyone else, especially her daughter. She liked giving little gifts and never visited someone empty-handed. She’d offer the food off her own plate if she didn’t have anything else to give. She had a soft spot for elderly people.

How can this be all? How can I pour her entire life into a few short paragraphs?

This is where I get stuck. I never did find a good guide to Chinese obituaries to offer a second opinion, but according to Funeral Basics’ guide to writing an obituary, after writing the biographical information and a few optional personalized lines, this is where I would mention the family members who preceded her in death, as well as the loved ones who survived. But how can this be all? How can I pour her entire life into a few short paragraphs? Where do I include her love of steamed buns and how her father snuck her an extra from his school each day when she was growing so quickly her bones ached? Or her love of sesame mochi balls and pizza crusts later in life? Or how she dreaded the task of washing her mother’s feet, shaped into painful hooves from childhood to be more attractively helpless. Or the older brother who was so good natured and trusting that everyone thought he was simple, blamed his simpleness when he drowned in the river in his twenties, and how that shaped the rest of her life imperceptibly. How charmed she was when she first moved to America by the Amish, who were so trusting that they left their shop unattended, with only a jar for customers to pay for their wares. How do I fit them in the same sentence as the gentle scholarly father-in-law she admired and the fierce mother-in-law who clashed with her because they were so alike?

Let’s try again. People were drawn to Lisa’s liveliness, humor, and tenacity, and she picked up lifelong friends everywhere she went. In Pittsburgh, determined to return to a role in education like the one she’d left in China, she knocked on every door of the university until she was hired as a technician in a diabetes lab. When the professor said she didn’t have any experience, she protested that she would never have experience if no one ever gave her a chance. As in the rest of her life, when one door closed, she tried another. When all doors closed, she knocked down a wall to make one. One of her first American friends was her Polish American landlady Stella, who would give her baby clothes and write long letters to her in elegant script for over a decade after she moved across the country. Out west, in Las Vegas, she started her life over with the same resolve that marked everything she did. While working as a restaurant manager, she befriended Jim, an older gentleman and scholar who sometimes ate lunch there. When she learned that he was teaching himself Chinese, she was so delighted that she offered to give him lessons. Her daughter called him Grandpa and his wife Grandma, and even did a school report on how the Great Depression shaped his life. Their families remained close through all her subsequent life transitions, even living in the same neighborhood for a time.

There’s still so much I haven’t told you, so much I don’t even know about her life before she was my mother, the proud tender-hearted human she continued to be in addition to being my mother. Perhaps this is why, instead of writing two paragraphs a decade ago, I left it at only a sentence, unable to fathom the finality of her obituary and her death. I think what I really want is for people to miss her as much as I do. I want her life and her death to matter to everyone, or at the very least to matter this much to someone living besides me, because I’m not enough to hold all this mattering.

According to the earlier guide, the last step to writing a “great” obituary is to review it for mistakes. Like a poem, I’ve rewritten this in my head what feels like a thousand times, and it’s always missing so much. So perhaps also like a poem, I’ll revise periodically until language leaves me. I keep returning to Victoria Chang’s poetry collection Obit, in which she meditates on the many small deaths of memory and language that occur when a mother dies. In “The Head,” she writes, “Somewhere, in the morning, my mother had become the sketch. And I would spend the rest of my life trying to shade her back in.”

______________________________________________________________

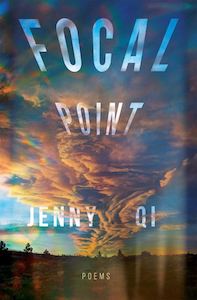

Jenny Qi’s Focal Point is available now via Steel Toe Books.

Jenny Qi

Jenny Qi is the author of the debut poetry collection Focal Point, winner of the 2020 Steel Toe Books Poetry Award. Her essays and poems have been published in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Tin House, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere, and she has received fellowships and support from Tin House, Omnidawn, Kearny Street Workshop, and the San Francisco Writers Grotto. Born to Chinese immigrants, she grew up mostly in Las Vegas and now lives in San Francisco, where she completed her Ph.D. in Cancer Biology. She is working on more essays and poems and translating her late mother’s memoirs of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and immigration to the U.S.