How to Write a Memoir About Family Tragedy (That People Want to Read)

Abi Morgan: “Nobody wants to read therapy.”

I’m a screenwriter. And as a screenwriter, I am used to the business of the rewrite, the brutal discard of a much-loved draft at the eleventh hour. But when Jacob, my partner of 18 years collapsed with a brain seizure, nothing prepared me for the scrapping of my carefully worked out narrative. A life previously entwined with children, family, good friends, busy careers, familiar highs, and lows, was now irreversibly damaged. When it hit me, it hit me square between the eyes. So, I did what I do with anything complicated or overwhelming: I started to write.

Writing from my own life when life becomes more brutal than anything I could have written, my internal editor went into overdrive. In hospital corridors, consultants became “characters.” Medical crisis became “essential plot.” My own children were not even safe from the steely gaze of the writer, as I noted down and edited “dialogue.” The sigh and peep of respirator and heart monitor, the soundtrack to this film. In the worst moments, I would pray for a director to shout “cut.” But life is not a film, or a play, or a memoir. It’s lived, with “no exit stage right.” There was no moment where I knew the movie would end and I would get to stand up from my seat, and walk out into the light.

Whilst the doctors, nurses and therapists were saving my partner, bringing him back to life, writing late at night in my kitchen kept me sane, kept me wanting to live. It was a quiet act of defiance that grew to a fury—I kept voice memos, sent texts, and wrote long and meandering What’s Apps messages to anyone that would listen. Transitioning from the intensive care unit, into rehab, and then home, I wrote and rewrote the narrative in my mind, determining that there may one day be a play or a film in it.

Metaphor was everywhere and often in opposition, thrown when a consultant likened recovery “to like running a marathon not a sprint.” Cognitively, his neuropsychiatrists described it as if he was “lost in the woods.” On bad days I would imagine him deep under water, struggling not to drown, or spinning far out in space, grappling with these conflicting images, and searching for cohesive themes. Writing down life in granular detail, I navigated the dark and at most difficult times. The hardest part, grappling with the left of field plot twist.

I reviewed the most painful moments of pure tragedy with the forensic eye of a surgeon, snatching the joy and milking the pathos from the worst times.

The first? Waking after 6 months in a coma, Jacob, though clearly changed, smiled and blinked in recognition of those he loved around him. As a family we rejoiced, comforting ourselves that the drama was over. When asked only a few months earlier if I feared the ultimate trope, that Jacob would wake and not remember me, I had rebuked the notion as too much of cliché. Yet as Jacob slowly and painfully acclimatized himself to the world, learning how to walk, talk and live again, it became apparent that something was very wrong. Capgras Delusion or the belief in doubles, gripped Jacob with a quiet fervor, and was focused on me. I was not the real “Abi Morgan” but an imposter who was fooling everyone but him.

The second? My own health battle—a pain in my chest that put down to the rub of a seatbelt as I drove in and out to the hospital on visits. Then, diagnosed three months into Jacob’s rehab as Stage 3 grade 3 breast cancer. My main response—anger and irritation. Once more I told myself in the movie “I’ll cut this bit.” Put simply, it was not only my identity that was now being brought into question but my very mortality, the looming deadline that I had largely ignored and hoped I’d never hit. The final insult and further proof that life is far from being stranger than fiction, but the cruel edit of the living to be plundered, hashed, and rehashed again and again on screen.

As 2019 tipped into 2020, so the world tipped into global pandemic. Theaters and cinemas closed, and I found myself rethinking the notion of a screenplay altogether. But I still wanted—and needed—to write this story. I began reading up on how to write a memoir. The first rule, it seemed, was not to make the memoir therapy. Nobody wants to read therapy. Certainly, the writing of a memoir, in the words of the author Isabelle Allende is “an exercise in truth.” Writing became my act of resistance. In the early months of lockdown, life was filtered for us all through laptop and Zoom.

The one gift that I have honed is the ability to shape a story, to make sense of it.

I pored over the diary I kept for the first 100 days whilst Jacob was in intensive care, shaping the first third of the memoir. The WhatsApp messages, Google articles, emails, and text messages I wrote to friend, family, and consultant, capturing both the early months and rehab. With Jacob, my living, and at times barely breathing, muse.

Logging the tiny detail, the blistering lines of dialogue, I reviewed the most painful moments of pure tragedy with the forensic eye of a surgeon, snatching the joy and milking the pathos from the worst times, as Jacob shakily found his way home, and this is what I came to see. As I gained strength and understanding through my writing of who I was, who we were, what we had once been, I came to see the person who had most lost his narrative, who was most in search of a script, was Jacob.

Staring blankly at himself in the mirror when at last at home, I asked him who he saw reflected “I don’t know,” he replied. The person who he no longer knew was him, not me. Suddenly the memoir had another purpose. Not only was it the laying of the track of our lives together, of us, of me. Now I had my most important audience, my most important reader—Jacob. The writing of a memoir, a book that would tell him his story, that he may one day read.

Why do we tell ourselves stories? To comfort ourselves in the dark. To write them is driven by a desire to communicate, to stimulate, to reflect on what it means to exist. Never have I been more grateful that though I cannot dance, sing, or paint, the one gift that I have honed is the ability to shape a story, to make sense of it.

__________________________________

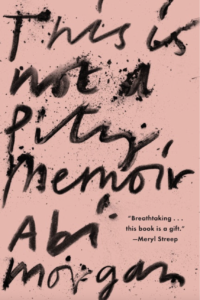

This Is Not a Pity Memoir by Abi Morgan is available via Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins, Inc.

Abi Morgan

Abi Morgan is a playwright and screenwriter. Her plays include Skinned, Sleeping Around, Splendour (Paines Plough), Tiny Dynamite (Traverse), Tender (Hampstead Theatre), Fugee (National Theatre), 27 (National Theatre of Scotland), Love Song (Frantic Assembly), and The Mistress Contract (Royal Court Theatre). Her television work includes My Fragile Heart, Murder, Sex Traffic, Tsunami – The Aftermath, White Girl, Royal Wedding, Birdsong, The Hour, River, and The Split. Her film writing credits include Brick Lane, Iron Lady, Shame, The Invisible Woman, and Suffragette. She has a number of films currently in development. Morgan has won a number of awards including Baftas and an Emmy for her film and TV work.