How to Skewer a Novel: Éric Chevillard on Florian Zeller

A Legendary French Critic Weighs in on "a book to laugh at and then forget."

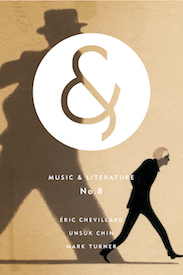

The following piece originally appeared as part of Éric Chevillard’s weekly column in Le Monde des Livres, which ran for six years prior to its end this autumn. During this tenure, Chevillard established himself as a fine reader and an extraordinary critic. This piece was recently published in Music & Literature no. 8, which collects over 150 pages of new and newly translated materials on and by Chevillard, and whose cover features the illustration (below) by Jean-François Martin that accompanied the French publication of this text.

![]()

It can be risky for a young writer to expose himself or herself to the influence of a master. Doing so is like exposing oneself to x-rays: beneficial at first, helpful as a tool of self-knowledge, it offers a sound training in boldness and radicalism. It burns away fatty layers of voracious, careless, maladjusted post-adolescent reading. And then it keeps burning, destroying immune defenses, attacking the bone. The master’s influence eventually reduces the disciple to ashes. His or her books will henceforth be but pale, grimacing shadows of the oeuvre that inspired them.

In any case, important writers have no truck with the apes who would ape them; they have no desire to see, in these cross-eyed mirrors, their faces reconstituted in flyspeck. The true master teaches liberty, and thus solitude: he chases us out of his orbit the day we become of age. He has marked out a territory where everything has been said, where we can do no better than to trample his flowerbeds.

All of this is what Florian Zeller seems to have failed to understand and consider. His new novel, Pleasure, visibly reflects an ambition to add to the bibliography of Milan Kundera: alas, an unreasonable and desperate ambition. Everything is present, however, more or less: short chapters alternating episodes in a sentimental story of variable geometry with sociopolitical musings on the zeitgeist; a lexicographer’s attention for certain revealing terms carefully embroidered in italics on the page (here, for instance, contradiction and negotiation); the ambiguous posture of a narrator who intervenes from time to time to comment on the situation; and sex, again, as both impetus and telos of even the smallest acts. Of course, it would be naïve to reduce Kundera’s work to such a list, but this is quite precisely what Florian Zeller has done. One can almost see him cracking eggs and pouring flour into his mixing bowl, tongue between his teeth, squinting at The Book of Laughter and Forgetting as one would consult a cookbook.

Result: a book to laugh at and then forget, an undercooked Kundera that is not nourishing but still sits heavy in the gut. Comparison against the original is brutal for this gauche, immature story: another steer sinking into the pond in a vain effort to pass itself off as having the sinewy, shapely legs of the frog.

Pleasure, subtitled A European Novel, strikes up a totally artificial parallel between the evolution of a young Parisian couple, from their meeting to their parting, and that of the continent, from the political establishment of Europe to the present financial crisis. So, when Nicolas plans to spice up his life with Pauline by adding Sofia to their lovemaking, Florian Zeller hazards the following comparison: “If France and Germany invited Poland into their bed, should they be surprised if Poland, with its talent for pipe-fitting, weakens their interior equilibrium?” Later, after a conjugal spat: “But, just as Mitterrand shook hands with Kohl in front of the war memorial at Verdun, Pauline and Nicolas made up—and there they are now in bed, in full European congress.”

And so on, in the same savory register, until the separation of the two lovers and “the potential exit of Greece and Portugal from the European Union.” We can see that the parallel is fruitful, each story serving as a pointless metaphor for the other. The charade might be formulated in these terms: my first is my second, my second is my first, and my all is a lugubriously showy book that ultimately proves absolutely nothing.

And see where it says: “She had not managed to heal from that strange malady known as childhood.” Or: “Nicolas remained pensive for a long moment. Painful images blossomed in his head.” (Indeed.) Pleasure is one of those books marked by occasional ashes of awareness of its own insignificance, to which it responds rather disloyally by holding its characters accountable: “He could easily have had what his father called ‘a real vocation.’” The cliché is isolated and called out as such, but the author does not puncture it, does not surpass it, just stops there and fails to find anything better.

This dopey style reaches its apex, logically enough, in a scene of sodomy. Nicolas, long attracted by “that little rosy circle,” decides one day to venture into it. His companion agrees. “The little orifice shone like a black star.” He “entered her from behind. Her breathing changed, its rhythm. It was no longer a symphony. More like Für Elise. Some slow notes. Difficult ones. Before the melody took off.” Lovers of pornography and music alike will run, not walk, to demand their money back from the bookstore.

Despite a case of name-dropping as presumptuous as it is prestigious—look out for Queneau, Breton, Bergman, Beethoven, Godard, Cioran, Sartre, Leiris, and Kubrick—Pleasure usurps its title and leaves us, on the contrary, painfully unsatisfied. Oh, the unbearable heaviness of literature, sometimes!

__________________________________

From Music & Literature no. 8. Translated by Daniel Levin Becker.