How to Throw a Shower for a Novel

Caroline Louise Walker on Celebrating a Very Important New Arrival

As an adult, I’ve rented zip codes from coast to coast, but the fact remains that I took shape in the middle of the Midwest, where modesty is currency. Things that make my stomach twist: vanity, self-indulgence, self-importance, the threat of having to speak in public, the very thought of a party being held in my honor. And so it went firmly against my nature when, recently, I sent something like the following invitation to friends, family, and strangers across my hometown:

YOU ARE INVITED

to a Novel Shower

What: a party celebrating a book and its author

Why: because more than a few rites of passage are worth celebrating

Registry: all gifts from registry support classrooms across Rock Island Public School District 41, where the author learned how to write

I planned my outfit. I asked a friend to take photographs, please.

It should have been torture, throwing my own party in my own honor, but I threw it anyway and stood in front of a crowd and spoke, my gut forgetting to twist when I made the point I’d come to make, which was a moment I won’t soon forget, because marking the moment was the point. The whole point. To my astonishment, it wasn’t torture at all.

We’d gathered together to welcome my first novel into the world—a book about a man who is very comfortable celebrating himself, and about the women in his life, who tell a different story, because they’re experiencing a different reality. At last, I’d released my changelings into their wild: spines out, on shelves and in shops in New York, Iowa, Estonia, in places I’ve lived and towns I’ve never seen, and in the hands and homes and strangers. This fact hooks me with equal parts grief and relief.

If I did it again, I’d do it bigger and louder, and I hope someone does, then tells me about it.

It has been my experience that writing a novel requires commitment, compromise, endurance, vulnerability, patience, honesty, hope, and love, and invites Love’s shadow side, and heartbreak, and exhaustion. It is work, and it is a relationship, too. At some point during edits, my mom and I joked about throwing a baby shower for my book when the time finally came. I exhausted the joke by detailing a hypothetical gift registry: iMac, standing desk, cash funds to freeze my eggs, cash funds to pay my student debt, cash funds for health insurance, heaps of pencils, new hard drive, a bazillion copies of my novel.

Of course, a book is not a baby, and career isn’t family. Traditions are specific for good reasons. The more I joked about a traditional shower, however, the more I thought about its good reasons for specificity, is origins sunk in dowries, hope chests, coverture laws, salvation from the doom of spinsterhood.

But times have changed. Today, there’s nothing damning or radical or fringe about being uncoupled or not having children, which is precisely why the shower-as-party seems so absurdly antiquated to me. Tradition teaches culture, passed down through generations. We demonstrate values when we show young people which choices we find significant or worthy of reward, and our choices have expanded a great deal since the nascent days of bridal showers.

Tradition taught me this as a girl: showers sound purifying but look like small sandwiches and new appliances. Get engaged, you get an electric mixer. Stay unmarried, you can do that shit by hand. But also: laughter, love, friendship. Women springing into action to celebrate each other, carving space for the honoree to pause and feel the weight of this extraordinary moment in her life—provided the moment is marriage or motherhood. In such cases, her transition will be tethered and softened by witnesses granting safe passage to the rite. Otherwise, “your time will come.”

Of course, tradition taught me other things. For example: people write books.

When I was in elementary school, a few parents and teachers put a typewriter and desk in a study room connected to the school library and called that room The Writing Center. Volunteers typed up students’ fables, rubber cementing our illustrations onto pages, decorating cardboard covers with patterned Con-Tact paper. The creation and consecration of our spiral-bound stories existed outside of the classroom. Ungraded, unjudged. Participation was not mandatory or micromanaged, which allowed it to feel especially freeing and personal when—once a year, one at a time—we’d slip away from homeroom to unleash our imaginations in the Writing Center, where our wildest and weirdest ideas were treated with respect.

For me, the resource functioned as secular ritual, its significance made tangible by ink on paper. My third grade “About the Author” page says, “Caroline loves to write and has written many books.” Because of this experience, I knew books came from writers.

There’s no Writing Center in that school library now.

The public school district where I attended K-12 currently receives Title I assistance. Basic supplies are in short supply, to say nothing of arts programming. I think about the books and music and policies those students might write someday, and what we steal from kids and from culture at large when we deny them the basic tools necessary to do their jobs. It’s not that I wouldn’t enjoy an iMac or cash funds. (I currently use a cardboard standing desk. I don’t really have a home.) But when the alchemical salt rose from my joke-that-had-stopped-being-a-joke, my wishes crystalized: creative fuel, great books, music that hasn’t been written yet

*

I partnered with an organization running successful school supply drives in the area for decades. I printed invitations and built a website. I called the party a shower, not to be cheeky, but to activate muscle memory for guests, holding my life to the same standard I’ve been trained and taught to uphold for others.

Gifts poured in, all delivered directly to the local First Day Fund. The event itself was standing room only. My first grade teacher was there. My kindergarten teacher and high school English teacher and high school guidance counselor, too. Former classmates I hadn’t seen in decades. Friends I’ve known my whole life. If I did it again, I’d do it bigger and louder, and I hope someone does, then tells me about it.

The night was electric and full of love, but after the stardust settled, I sat down to write about it and found myself running interference, addressing my assumptions about your assumptions about my thoughts on love and motherhood. Tripping on admissions and concessions and disclaimers—details that increasingly resembled explanations (that increasingly resembled apologies)—my frustration hardened. Of course it would. I was trying to write the why, when the real why is to not explain myself in the first place, to not make a case for my happiness, to not defend my choices or their value; because a defense exists through its relationship with an opposing force, and this isn’t a fight.

By marking a moment that could easily have slipped into the next, acknowledgement became the monument. I signed books at a long table draped with a stained roll of canvas, its giant, hand-poured inkblot taking up so much white space, demanding visibility. I took up space, too. It was novel, and it was significant, and there was no need to campaign for creativity as virtue. By showing up to help stretch tradition, everyone there was already on board.

Photos by Tara McFarland.

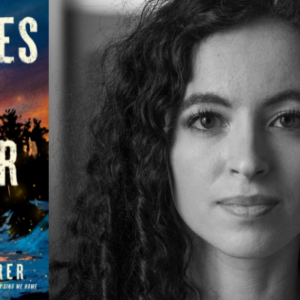

Caroline Louise Walker

Caroline Louise Walker grew up in Rock Island, Illinois. For her fiction and nonfiction, she has received fellowships from The MacDowell Colony, The Kerouac Project, and Jentel Arts. She holds an MA from NYU. Man of the Year is her first novel.