How To Think Like a Woman: A Brief Accounting of Unacknowledged Philosophical Genius

Regan Penaluna on Female Philosophy and the Risks of Being Too Smart Throughout History

Very little is known about philosopher Gārgī Vācaknavī, who lived in India 2,800 years ago. Some things I want to know: When did she first notice her hunger for abstraction? Did she study with her father the sage? Did the “woman question,” in some distant yet familiar form, haunt her psyche, too?

Her story, reported in an ancient text, goes something like this. King Janaka, the Hindu king of Videha, invited the brightest minds of his kingdom to his court for a debate, promising to reward the wisest with the prize of gold and a thousand cows. Gārgī was among the guests and the only woman of the sizeable gathering invited to speak.

At the start, Yājñavalkya, a famed Hindu philosopher, who said he was the superior debater, claimed the prize for himself without ever debating, which angered the other sages and kicked off a fierce debate. Each sage took a turn arguing against him but dropped away in defeat. Only Gārgī was able to hold her own.

She was fascinated by the nature of reality and suspected that water underpinned everything. (Over a century later, the first Greek philosopher, Thales, proposed a similar idea.) She was also concerned that such a belief could slip into infinite regress: What substance supported water, and in turn, what substance supported that? She asked Yājñavalkya this question, and then another. Yājñavalkya shot back: “Gārgī, do not ask too many questions, or your head will shatter apart.” She questioned him further.

What’s interesting is that Gārgī, clearly the superior debater, did not take the prize. Perhaps she understood that because she was a woman, the award was never hers to have. At the end of the debate, Gārgī turned to the other sages and declared Yājñavalkya the winner—a gesture that when seen from a certain angle placed her in the superior position of judge. She told the sages: “None of you will defeat him.” But perhaps she thought she had.

Another woman of renown in King Janaka’s time was Sulabhā, a Hindu nun known for her mastery of rhetoric and yoga who wandered the land on her own in pursuit of truth and freedom—an existence she much preferred to marriage. She believed there was no difference between men’s and women’s minds and that women could also be sages. When she heard that Janaka believed himself to be wise, she had her doubts. So she traveled to meet him and learn for herself.

Upon her arrival at court, she addressed Janaka: “Most excellent seer in the Kuru line of kings! Who has acquired the training using understanding alone, without giving up the householding life? Tell me the true principles of Absolute Freedom.” For Sulabhā, wisdom was a form of spiritual freedom that required a state of detachment, and it was unclear how such freedom could coexist with power. Janaka told her he’d studied with a great sage who taught him how to be both free from the world and in control of it, an argument that did not persuade Sulabhā.

This only angered the king, who questioned whether her claim to freedom was due to insight, as she professed. “Or maybe you are on your own, free of a husband through some fault of your own,” he said. He added that her yoga, which she was practicing as he spoke, perturbed him.

Now Sulabhā had the answer she sought. That she could disturb Janaka so easily was evidence he was not free or wise. And as for her lack of husband, she said, “Since there was no husband suitable to me, I was trained in the rules for gaining Absolute Freedom.” She thanked Janaka for his time and promised to depart in the morning after a good night’s sleep. Alone.

The Pythagorean women were welcome to express their thoughts—as long as they conformed to the male prerogative.

Around the start of the sixth century BCE, while some of the first Greek male philosophers were putting forth their ideas, Cleobulina of Rhodes accepted the job of soaping and scrubbing men’s calloused and warty feet. It was a calculated move on her part. These feet belonged to the thinkers who came to the home of her father, one of the “seven sages of Greece,” and this was her opportunity to discuss philosophy while fulfilling her female duties. Her mind grew sharp as she lathered toes and exchanged ideas about reality. She eventually wrote a work of mind-bending riddles that would be celebrated for hundreds of years and that Aristotle would admire.

In the third century BCE, the Pythagorean philosopher Phintys defended women’s right to study philosophy. “Now, perhaps many think it is not fitting for a woman to philosophize, just as it is not fitting for her to ride horses or speak in public,” she said. “I say that courage and justice and wisdom are common to both sexes.”

Other fragments believed to be written by Pythagorean women philosophers suggest they didn’t challenge traditional gender roles so much as double down on them. They wrote that a woman is to be a good wife: she is modest (even her elbow is covered), raises the children, isn’t adulterous, yet endures her husband’s regular visits to prostitutes.

It seems, then, the Pythagorean women were welcome to express their thoughts—as long as they conformed to the male prerogative.

Aspasia was a prominent member of Athenian society in the fifth century BCE and consort to Athenian general and statesman Pericles. Originally from Miletus, Aspasia was a resident alien in Athens, a status that prevented her from legally marrying Pericles, and so to make herself acceptable to elite society, she adopted the title of hetaira, a high-class prostitute. Ancient and modern historians get tangled up in questions of whether she was in fact a courtesan or if she ran a harem.

But I find her fascinating for additional reasons. She taught rhetoric, and one of her more famous students was Socrates. She described the natural world without reference to deities. Because of this, she may have been put on trial for questioning the gods’ authority—years before Socrates faced a similar charge.

Diotima was another teacher of Socrates and appears in Plato’s dialogue the Symposium. Socrates says her thinking inspired his own about love, knowledge, and immortality. Still, some historians tell us that she did not exist, which, if true, would make her the only fictional person Plato created.

Around 375 BCE, in the lush valley of the ancient Greek city Cyrene (in what is modern Libya), lived a woman called Arete. Her father was a student of Socrates who opened his own school of philosophy, which Arete eventually took over. She taught theories of nature and morality to more than one hundred students and wrote forty works of philosophy, although nothing of her writing remains. It’s a shame. I wonder how much of her intellectual vision was like her father’s, which advocated indulgence in immediate pleasures, including having sex with prostitutes.

Did Arete acknowledge the ethical dilemma of what to do if the immediate pleasures of the courtesan were in direct conflict with those of her john? Or perhaps women’s subjectivity flowed past her, just as it had flowed past her father, invisibly, as air.

After reading Plato’s Republic, Axiothea left her home in the Spartanruled mountain valley of Phlius to study with Plato. Around the same time, another woman, Lasthenia, left her home in the highlands of Arcadia to do the same. There are no records of their ideas or whether they composed original works. What impressed ancient historians was that they were allowed into Plato’s Academy and that they wore men’s clothes.

In the third century BCE in Greece, the philosopher Hipparchia fell in love with the Cynic philosopher Crates, telling her parents she would kill herself if they wouldn’t let her marry him. Crates warned Hipparchia that he had no wealth and could only offer her the life of a philosopher. She wanted that life, even though it entailed justifying herself to ornery men at dinner symposiums.

To one such drunk interlocutor, a man who could not keep up with her argumentation and so resorted to criticizing her housework while lifting up her tunic, she said, “Do you think I have done wrong to spend on the getting of knowledge all the time which, because of my sex, I was supposed to waste at the loom?”

In 310 CE, a century or so before western Mediterranean civilization would dip into an age of relative darkness, lived a woman named Sosipatra. She was the rare woman philosopher who was also a mother. (The next mother-philosopher in the West that we know about is Heloise, who lived 800 years later.)

After her husband left or died—the ancient sources aren’t clear which—Sosipatra raised her three sons alone in Pergamum, a vibrant city 16 miles from the coast of the Aegean Sea. There, in the comfort of her own home, she founded a school of philosophy and taught theories of the soul and immortality.

Hypatia, who was born in the late fourth century, was known to be the most brilliant person in all of Alexandria, eclipsing her father, a well-respected mathematician. She chose to be unmarried so she could devote herself to studying and teaching mathematics and philosophy, a decision which some men had trouble respecting. What was a woman to do in this situation? To one pesky suitor Hypatia offered her menstrual rag rather than her hand.

She was fascinated by the geometry of ellipses, composed elegant long-division solutions to astronomical problems, and refined an early version of the astrolabe. As a Neoplatonist philosopher, she believed the ideal world was more real than the material world. Such a view did not keep her from offering political advice. She counseled powerful men to seek discourse over violence in a city fraught with tension between Christian, Jewish, and pagan factions. This was to be her undoing.

In 415, a mob skinned her alive with oyster shells, pulled out her eyes, and dragged her body through the streets. When news of this cruelty reached the rest of the Roman Empire, people were horrified. Ever since, historians have tried to make sense of it: Was she the victim of a crossfire between dueling political factions? Was her death prompted by a hatred and fear of what she symbolized: elitism and paganism? Was the mob ignorant, confusing her astronomy for witchery? Or was it that she was a smart woman with political influence and so seen as a threat to social order?

__________________________________

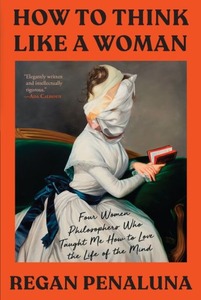

Excerpted from How To Think Like a Woman. © 2023 Regan Penaluna. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Regan Penaluna

Regan Penaluna is a writer and journalist based in Brooklyn. Previously, she was an editor at Nautilus magazine and Guernica magazine, where she wrote and edited long-form stories and interviews. Her writing has also appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Philosophy Now, and the Philosophers' Magazine. Penaluna has a PhD in philosophy from Boston University and a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University. She is the author of How to Think Like a Woman.