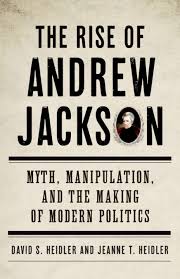

How to Sell a Candidate to the Public: Andrew Jackson Edition

On the Dark Tradition of American Populism

The candidacy of Andrew Jackson was the first modern presidential campaign in American history, the first instance of deliberate image building and mythmaking and of skillful manipulation of public perception and popular opinion.

American politics had from the beginning featured candidates mixing with the people and even holding social events. “Swilling the planters with bumbo” was the custom of plying voters with a rum-based punch, but the scope of such behavior was limited by the small number of men who had the right to vote. Even the largest instance of widespread activity before the 1820s was on a fairly small scale. John Beckley, the first clerk of the House of Representatives, did work in Pennsylvania for Thomas Jefferson during the elections of 1796 and 1800 that foreshadowed Jacksonite practices of the 1820s. Beckley enlisted local leaders to write letters and blanketed the countryside with ballots of Republican electors to establish name recognition for Jefferson’s ticket. But Beckley anticipated Jacksonite innovations primarily in his willingness to enter the fray of partisan politics, which the Founding generation spurned as unseemly. To be sure, the gentry rule that the presidential office should seek the man rather than the other way around was not always strictly adhered to. But appearing to obey it prevented the use of practices associated with a national campaign.

The broader acceptance of outright politicking in the 1820s disclosed a major shift in attitudes about the proper methods of winning elections. The men who achieved Andrew Jackson’s transformation into a political force saw nothing unseemly about the way they went about it. They groomed him, protected him, and belled the cat of his temper. They published quaint stories of his kindness and heroic tales of his courage. They contrived ways to make him seem measured and statesmanlike. They made him the friend of debtors (he dismissed them as deadbeats), the advocate for low tariffs or high ones (he had no opinion on the matter), and the enemy of grasping bankers (who were some of his best friends). He was made an icon in the tradition of George Washington, though he had been among those most critical of Washington at the end of his presidency. Jackson was made the ideological heir of Thomas Jefferson, though he had openly opposed President Jefferson, and the Sage of Monticello himself was openly dismayed by Jackson’s rising popularity.

“Though historians have looked at the elections of 1824 and 1828 as culturally, politically, and socially transformative, no one has provided a thorough telling of how Jackson and his managers created a candidate and sold him to the American people.”

Such obstacles were minor inconveniences for clever men with supple scruples. At first, armed with little more than intuition and flinty resolve, Jackson’s promoters linked him with the spirit of discontent that emerged after 1815. From those initial efforts, a gradual blurring of the movement and the man proceeded until he ceased to be the beneficiary of a popular program and instead became the personification of it. By then, the little group of intuitive and resolute men had become legion, and they were being organized by Van Buren, a mastermind with a national vision and the ability to make all things seem local. By then, Andrew Jackson had become wildly and irresistibly popular. He was meant to be.

The Jacksonites also innovated within existing political practices. Newspapers had been a part of politics in colonial times, though libel laws discouraged direct attacks on opponents, a restriction that vanished by the 1790s when Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton used rival newspapers to promote their views and attack opponents. The Jackson campaign pioneered uses for newspapers during the 1824 campaign. After Jackson lost that election in the House of Representatives to John Quincy Adams, Jacksonites increased their efforts to spend money as no campaign had ever done before. They financed editors to encourage attacks on the Adams administration, and where no papers friendly to Jackson existed, they founded them. Their newspaper network’s highly disciplined message appeared in stories and opinion pieces pulled from subscription services and reprinted in local sheets in ways that prefigured the tactics of a modern press syndicate.

This was only one hallmark of a finely tuned and an always improving organization. Starting with the Nashville Junto, Jacksonites became adept at coordinating local activities on a national level. During the 1828 campaign, they set up committees at important hubs and staffed them with influential community leaders who were, in turn, directed and controlled by central committees in Washington and Nashville. These forerunners of Republican and Democratic National Committees instructed localities to hold Jackson rallies and parades, raise (Old) Hickory Poles, and distribute inexpensive likenesses of Jackson along with gimcracks lauding him and denouncing his dwindling number of critics. They organized straw polls after prudently determining favorable results, and they held mass public meetings to pass resolutions the local committee carefully drafted to ensure acceptance. The dutiful Jackson press covered everything with a consistent message rendered in sufficiently different language to create the appearance that support for the Hero was not only massive but spontaneous and diverse.

At a time when political parties were still considered soiled creatures of faction and parasitic entities that divided the nation, Adams men discovered too late that the tight organization of dissimilar coalitions had become the key to victory. Though Jackson’s supporters did not constitute a distinct party—everyone called himself a Republican during those years—they began behaving like one, and their opponents gradually realized that disdaining the new methods of politics was a sure path to defeat. They watched helplessly as Jacksonites learned from their loss in 1824 and proved amazingly agile and able to attract talented people to their cause.

Though historians have looked at the elections of 1824 and 1828 as culturally, politically, and socially transformative, no one has provided a thorough telling of how Jackson and his managers created a candidate and sold him to the American people. Unabashed admirers of Andrew Jackson are fewer now than in times past, but their work still dominates the historical landscape by its sheer volume. Nowadays critics eager to denounce Jackson grow in number because they condemn him as a racist whose attitude toward Indians alone merits his banishment from the American pantheon as well as American folding money. The admirers have a tendency to lionize Jacksonites as Jacksonians with talk of common men rising and ordinary people gaining political clout. The critics hold in contempt the people who supported Andrew Jackson as racists themselves, as people spitting, scratching, and cussing while skinning their knuckles on the dirt floors of their jerry-built shacks. For our part, we have labored to move beyond or, better yet, before caricature. Our aim is to understand Andrew Jackson, to comprehend the supporters who shaped his candidacy, and to hear the voters who made him president.

“The cunning men behind Jackson’s candidacy convinced a plurality of the American people in 1824 that Andrew Jackson was on their side, whatever side it was.”

Because there were no formal political parties and factions supported a variety of favorite sons, it is easy to conclude that the campaigns of the 1820s were popularity contests devoid of issues. But doing so misses the point. The cunning men behind Jackson’s candidacy convinced a plurality of the American people in 1824 that Andrew Jackson was on their side, whatever side it was. They made the people believe he shared their concerns, whether they planted cotton in the red clay of Georgia, worked a lathe in a moteshot Philadelphia shop, or scored the earth for DeWitt Clinton’s Erie Canal. When the numbers those people represented were insufficient for victory in 1824, Jacksonites and the man at their head redoubled their efforts at the methods that had worked, such as mass meetings, partisan coordination of the press, and lionization of their champion as a man of action forged by martial challenges. And after the failure of 1824 seemed to provide irrefutable evidence of corruption, they amplified their earlier calls to flush the sewer of national politics as practiced by the denizens of Washington, DC. They described the men there as having elevated the business of government over the people’s interests, confusing the meanings of self-interest and public service. Doubtless, many of them believed this, but others realized that it was enough to act as if they did, which could pass for a reasonable definition of politics in its modern form.

In the summer of 1845, a young portrait painter named George Healy arrived at Henry Clay’s home outside Lexington, Kentucky, to paint the great man’s likeness. Healy had just come from Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, where his portrait of Jackson would be the last of the old man from life. Withered and ailing, Jackson died shortly after the work was finished, but Healy had seen the younger champion of a political movement who gave his name to an age, and that is who he painted. This was by then an image of Jackson as imaginary as the one the men who made him president had created decades earlier, and both would prove enduring. Clay, curious about Healy’s opinion of a lifelong enemy, asked whether Jackson was a “sincere” man, in the sense of frankness, candor, and authenticity.

“If General Jackson was not sincere,” Healy said curtly, with the irritation of an admirer having to defend his idol, “then I do not know the meaning of the word.”

Henry Clay nodded with weary resignation over the young man’s apparent esteem for Jackson. He sighed. “I see that you, like all who approached that man, were fascinated by him.”

An entire generation of Americans would have said, Just so. As we will see, they had their reasons.

__________________________________

From The Rise of Andrew Jackson: Myth, Manipulation, and the Making of Modern Politics. Copyright © 2018 by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler.

davidandjeanneheidler

David S. Heidler is an author and retired professor. Jeanne T. Heidler is professor emerita of history at the United States Air Force Academy. They have collaborated on numerous books, including the critically acclaimed Henry Clay: The Essential American and the award-winning Washington’s Circle: The Creation of the President. Their new books, The Rise of Andrew Jackson is out now from Basic Books.