I.

One looks like the side of a boxcar: flat; rectangular; russet; and so the spots on its body are passable for graffiti. One, and another one nearby, look like experiments in italicized calligraphy. In the spell of a torch’s flickering, some seem to have the motion of tattoos on flexing muscles. But the fact is that our metaphors and modifiers fail: the beauty and mystery of the cave art animals obviously precede—and are forever beyond—our verbal decoration.

The images in Chauvet Cave are 32,000 years old, “four times as long as recorded history,” Judith Thurman points out. Our own world changes with dizzying rapidity: my grandmother’s life included Kitty Hawk at one end, Sputnik at the other, and that was before the weekly reinvention of Internet technofashions and the wham-bam jump-cut pace of music videos. But for 32,000 years the aurochs and stags and ibex and bison and horses and mammoths were created in the dangerous dark of caves in Spain and France with a consistency of look that makes their passage through the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian seamless; makes a single bestiary that has no need of change.

Increasingly, fewer of us will ever stand in the caves in front of them, although splendid books of photographs exist and, recently, Werner Herzog’s film of Chauvet. Whoever has (through chance, in the beginning; today, through bureaucratic permission) entered that hidden world of stone and dark, and stood there human-face-to-unhuman-face, records a transcendent experience, “holy,” “unearthly”; words like “power,” “vitality,” “grace” are common, often in a context that admits how sadly inadequate they are. These animals have a culminant hereness that we rarely find in their cousins at the zoo—or in our neighbors or, if we really have to put it this way, in our selves.

I’m thinking today about absence. It might be, at least in part, that a bison’s imposing grandeur is so intense because, as Thurman puts it, “nothing of the landscape—clouds, earth, sun, moon, rivers, or plant life, and, only rarely, a horizon—figures in cave art.” These are some of “many striking omissions,” she tells us. Maybe it’s because “no human conflict is recorded in cave art,” and because the artists (would they have thought of themselves as “artists”?) “rarely chose to depict human beings,” that the two does are so daintily imperial, and the lion says he will never yield to time, and the Megaloceros stag is as much at home in our brains as are their own convolutions. Maybe these animals seem so “here” because they feed on everything else that isn’t, the way the dancing flame fed on the lump of grease in the stone lamps they were painted by, and the way we cling to one another, wicking up the universe of dark matter that surrounds us.

Absence . . . I look at my hand, this hand that’s writing with a Bic pen in an everyday dime-store notebook, and was scraped along its outer edge when it tried to brace against a fall the other day (it looks like gray-tinged bacon), and was tended to by my wife, with soap and water, antiseptic cream, a Band-Aid, and a touch of spousal sympathy from her hand, just as light as a moth-wing’s brush. However, I’ve read enough in lay texts on 20th-century physics to know that between the atoms, and in the atoms, this hand is mainly empty air: a tiny spritz of elements held in an overwhelming void. The same for a two-by-four, of course, a pitted meteorite, an I-beam, a tusk. But human flesh . . . ? Yes, human flesh: a whiffle of “me” in a framework filled by absolute dead-on zero.

II.

Peggy Rabb was my colleague for a year, and now she’s gone. I’ve heard those same words, “power,” “vitality,” “grace,” applied to her, too. And her impish sense of humor. And the flea-market finds she begifted throughout the sixth floor, for no reason except her joy in life, to full professors and secretaries alike; I got a blue mesh bag of 1950s turquoise plastic typewriter keys. She bolted down bourbon and belted out hymns and limericks. Everyone misses her. Or everyone (it’s an English department, after all) who wasn’t secretly envious of her effortless charm. A year later, her name remains on her office door. I’m thinking today about absence.

How that door is such a real, knockable, tape-a-note-onable, solid thing—and floats, like the ocher rhinos of prehistoric caves, on a field of absence. How we all walk every day, all day, through unlimited meadows of emptiness: what happens between the toggled switch and the lightbulb’s watting to life, what line of transmission exists between the turn-on keystroke and the lit screen, or between the turned ignition key and the engine thrum. That’s Dimension X for myself and my friends. Most of us still live in a world of magic.

For an in-class essay one afternoon, a woman gilds her idea—that poets sometimes “juggle time”—with a fannish pop reference to Star Trek. As you probably know, the crew of the Next Generation series livens up its tedious travel through empty space by playing on the holodeck, having adventures with, say, characters from the Sherlock Holmes stories. “Holydeck,” she’s written. It’s a charming misconception—how can one not like it?—but it means she has no notion of how holographic simulation underlies the concept.

At the board, I chalk a church spire for them, and trace it through aspiration, inspiration, respiration, perspiration. “A ‘library’ isn’t a word pulled out of someone’s ass,” I say, and show them the libro inside it, and the way that open reading leads us to “liberty.” “Even ‘language’ itself”: I circle the lang—the tongue—and then put “cunnilingus” on the board. Most of us—me too, I insist—survive a day cane-tapping our way through structures we don’t see.

That’s what Bill Bryson claims: “I was on a long flight across the Pacific . . . when it occurred to me . . . that I didn’t know the first thing about the only planet I was ever going to live on. I had no idea, for example, why the oceans were salty but the Great Lakes weren’t. . . I didn’t know what a proton was, or a protein, didn’t know a quark from a quasar.” (Add to that, I’m willing to bet, what kept the plane invisibly held in the air.) And so he writes his marvelous info-larded best-selling A Short History of Nearly Everything. Facts, facts, facts. Except, because he’s honest, it’s also a history of what we still don’t comprehend—an annals of absence.

This is even more startling his next time around: At Home is a room-by-room history of the house in which he lives. Compare that compact span to the open-bordered aura of Nearly Everything! And even so, the facts, facts, facts, and their knockable doors and tiles and joists and balustrades, are all-over pocked like Swiss cheese with the empty holes of what we don’t know: “How Aspdin invented his product has always been something of a mystery” (page 223); “Why AT&T engineers chose the youthful Dreyfuss for the project is forgotten” (231); “a shadowy figure named Charles Bridgeman. Where exactly this dashing man of genius came from has always been a mystery” (256); “the fashion became to make things look natural. Where this impulse came from isn’t at all easy to say” (257); “Soon the woods of North America were so full of plant hunters that it is impossible to tell now who exactly discovered what” (265); “the whereabouts of the mortal remains of quite a number of worthies [then an on-rolling list] are today quite unknown” (271); “The identity of the vine owner is now lost, which is unfortunate as he was a significant human being” (277); “Yet, strangely, [Jefferson] didn’t keep a diary or an inventory of Monticello itself. ‘We know more about Jefferson’s house in Paris than this one, oddly enough,’ Susan Stein, the senior curator, told me” (295); “in the United States . . . it is known that about twelve thousand people a year hit the ground and never get up again, but whether that is because they have fallen from a tree, a roof, or off the back porch is unknown” (307); “No one knows where stairs originated or when, even roughly” (312).

This, from fewer than 100 pages out of 452, and all of it bountiful with emptiness.

(Amazing: we know more about the origin of stars than of stairs.)

As for me, I’ve decided to pioneer an existence that’s Internet-free. I’ve never touched a computer keyboard, not once. What follows—never sent or received an email, shopped online or paid a bill there, no eBay, online porn, or social networking, not one Google moment, or Nook, or Kindle, not one Wikipedia glance—is a willful illiteracy; is a life that’s increasingly anti-matter; a charcoal stag or a reindeer that’s itself, that’s more itself, because of everything it’s not.

The flame feeds off the lump of fat, as the bull on the wall feeds on the darkness.

Yes—and when in-person or postal paying-of-bills is no longer an option?

Mr. Bison Man, Big Aurochs Man, in the boulder-closed cave, with his frozen ecstatic leap across the cosmos, with the little spears drawn in his body.

III.

It’s common to suppose that a Luddite wants less. That’s what refusal must mean. But in fact a Luddite wants more—of the same. If I had enough space I’d devote an entire room to the museumly care of early manual typewriters. As it is, my few mementos of that vanishing world are dear to me . . . and the blue mesh bag of typewriter keys that Peggy gave me is doubly dear. Their gibberish jumble evokes an earlier world, when they were ordered, in rows, and created rows of language; just as they also evoke an earlier world when energy was ordered into a living system we all called “Peggy Rabb.”

She’d meet me for noshes or drinks and beautiful boisterous poetry gab. “No need to wander as lonely as a cloud today,” she’d say, and in a while there we’d be, talking the Lake District poets over cheese grits.

Now that diner is also gone.

It’s tough for my undergraduate students to think of Wordsworth as edgy and rebellious; he’s too fuddy-duddy rhythmic and seemingly prissy to their ears. But when I teach his sonnet “The World Is Too Much with Us” I always emphasize its radical—even dangerous—last lines. I say, “Just think about it. His is a far more uniformly (and uniformly policed) religious universe. He’s grown up with stories of people who were pilloried for criticizing the church. And here he’s outright saying that if it would only help him see the world again in its natural cycles, free of artificial factory time and market economy, he’d forsake his Christianity and return to the faith of an ancient religion. I’d rather be / A pagan suckled in a creed outworn . . . / Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea; / Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn. I mean—wow!

In his essay “Prehistoric Eyes,” Guy Davenport offers a similar wish, toward a similar reinvigorating . . . but Davenport’s retroencompass is millennia-long in a way that makes the briny Greek sea-gods seem contemporary: “I would swap eyes, were it possible, with an Aurignacian hunter; I suspect his of being sharper, better in every sense.”

He’s been contemplating the cave wall art and the bones that bear engraved lines, like the Sarlat bone—the rib of an ox—that was marked up with a flint buried 230,000 years ago. His mind is inquisitive and empathetic and laser-point sharp, and he’s read the scholars whose lifework is communing with these artifacts—he refers to “Alexander Marshack’s brilliant speculative study of prehistoric symbolism”—but still, he knows we ultimately bump against unknowingness: “the images on the Sarlat bone . . . mean nothing to our eyes.” They may be a “work of art, or plat of hunting rights, tax receipt, star map, or whatever,” but finally all we have to hold are “gratuitous assumptions about the creature we call Cave Man.” The bone is scored with 70 lines, and they tease us with radiant, gut-wrench, heart-exalting meaningfulness, the way a fifth dimension might—but entrance is denied us. “For this . . .” as Wordsworth tells us in his sonnet, “we are out of tune.”

The reindeer’s antlers rise up like the elegantly fractaled map of a riverine system. The bulls mate. Or they fight. Or they’re superimposed at random. At best we can guess, and our guesses are balsa-wood flecks on a turbulent sea of darkness. Once we were certain that the small rolled scrolls of clay that we’ve found in a scatter on some of the cave floors were the penis sheaths of adolescent males brought to the innermost sanctums for ritual initiation—or, anyway, symbols of phalluses. Now we think they were merely tests, scrolled up to see if the clay was of viable pliability, then discarded. Davenport: “Context has been the great problem of understanding [these images]. Breuil, a priest, tended to see them as religious; Leroi-Gourhan posited a sexual context. . . Marshack places them in time, in the seasons, and relates them to the hunt.” Impressive guesses, all. And when we’re finished bringing ourselves to these animals, there they still are, more than impressive, moving us in exactly the way they should: outside of history. Thurman quotes one scholar: “The more you look, the less you understand.”

We can’t find the words. We can’t get back to whatever words are appropriate: these animals are like the dreams we had in the womb. See?—“like.” It’s the best we can do. They bypass all of our articulation, powerful exactly because their presence doesn’t require it. Their strength is that they aren’t any vocabulary we can provide, or any of our vocabulary’s referents. As I said, today I’m thinking, hard, about absence.

In his daffodils poem, “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” Wordsworth is healed of psychic distress by remembering an encounter, a joyful encounter, with those flowers. But he needs to remember “in vacant . . . mood”—he needs a blankness. Only then, in that space, can the daffodils “flash upon that inward eye.”

This is the matrix, the nothingdark, the Mystery, that enables the horse to emerge like a cloud of muscle from its otherworld life, and the bulls to charge across a frieze that isn’t a frieze so much as it is an open-ended possibility-field, and the does to prance (or thunder) (or cavort) from a rend in the rock face that might be (or not) the first creation-vent in time, from which the creatures of Earth streamed forth in their fruitfulness, “two by two,” as we would learn to say in our own small way, so many millennia later.

I was the one who dropped off Peggy Rabb at Wesley Memorial Hospital, up on Hillside. It was no big deal, she said. It was stomach distress and constipation, and she’d get it checked out, but it was no big deal. She didn’t bring an overnight bag. She didn’t require a book or a magazine. And so I left her at the check-in counter. She turned around and smiled that great engaging veldt of a smile of hers, and waved, palm out, her fingers extended, something like a star a child would draw. Goodbye, she waved to me.

There aren’t many entire human figures in the caves. But there are the handprints—so evocative! Most of them were formed by placing the hand flat on the cave wall and blowing—through a tube—a careful aerosol of paint around it. That is, they’re negative images. Herzog ends his film about the caves with a long and steady shot of one of them, a shape in a mist of nearly unimaginably archaic red, burning into our memories.

The hand is here because it isn’t.

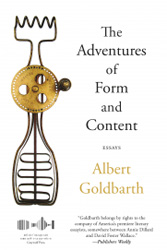

From The Adventures of Form and Content. Used with permission of Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2017 by Albert Goldbarth.