How to Pull Off a 250-Mile Protest March? Grit (And a Little Bit of Harry Belafonte)

Linda Sarsour on the 2015 #March2Justice

Harry Belafonte sat on a couch in his resplendent, wood-paneled office, telling us not to lose hope. The week before, several of us had been arrested outside Mayor Bill de Blasio’s house. We’d gone there to protest the decision not to hold the NYPD accountable for Eric Garner’s death, but our action had yielded no discernable result. Now, at a meeting of Justice League NYC, about 20 of us surrounded Mr. Belafonte. We were perched on chairs and literally sitting at his feet.

The great man was now well into his eighties but was as vital as ever. Even though his voice bore the slightest waver, his eyes were fiery as he told us about being with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis on the march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. Some 600 people had joined that 54-mile journey along Highway 80. On the fourth day, in a drenching downpour, they had camped out in a soaked field where a single flatbed trailer served as a concert stage from which performers sang and spoke in the rain.

Mr. Belafonte had organized it all, using his star power to bring out some of the nation’s most celebrated artists—from Mahalia Jackson to Leonard Bernstein, from Nina Simone to Joan Baez, from James Baldwin to Pete Seeger—all to support the cause of racial justice.

Mr. Belafonte described how tired the marchers were, yet how restored in their souls by the performance. Many of the protesters had been beaten and hosed. They’d faced snarling police dogs and some had been arrested, but the rest had marched on for freedom and equality, and so that people like us, sitting in this room, would have the right to vote and raise our voices, too. “There was no other choice but to keep going,” Mr. Belafonte told us. “Defeat is never an option.” He looked around the room, seeming to hold each person in his gaze at the same time. “All of you here have inherited the mantle from the ones who marched then, and we are all counting on you.”

For that entire meeting, I hung on his every word, feeling the great privilege of his belief in us to carry on the struggle. I was in awe of his commitment, which 50 years later was undimmed. Defeat is not an option, he had said, and with all my heart I believed him. That night, his grace, authority, and humanity felt like an infinite font of love, pouring sustenance into us all.

A month later the same group was once again gathered inside the same building in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, where Mr. Belafonte kept a suite of offices. We were seated this time around an expansive table of highly polished wood that commanded the center of the conference room. Around us, the walls were covered with photographs and awards from Mr. Belafonte’s long and illustrious career as an actor, singer, and agitator.

It would take us nine days to cross the five states between us and the nation’s capital.

The singer Paul Robeson had once told him that “artists are the gatekeepers of truth” and “civilization’s radical voice,” which is why, in addition to the Gathering for Justice, Mr. Belafonte had founded Sankofa, an organization to connect artists with grassroots organizing and social justice campaigns.

The Gathering for Justice was headquartered inside Mr. Belafonte’s suite, as was our own group, Justice League NYC. Our meetings there often lasted well into the night. No one ever wanted to leave. We rel- ished being in rooms that were imbued with Mr. Belafonte’s warrior spirit. It reminded us that our efforts were never in vain. However, the great man was not with us on this night, and the mood in the room was glum. “The police are just killing us and getting away with it,” Tamika said, throwing out her hands in a gesture of frustration. “This is not justice. We have to make people pay attention.”

“We can’t just keep doing press conferences,” someone else said. “We have to do something really outrageous so people will know we’re serious.”

Everybody started offering up suggestions, and then Tamika said, “Maybe we should march from here to Washington, DC.”

It was as if someone had opened a window in a gloomy place and light flooded in.

“Like Selma to Montgomery,” Carmen said, her imagination fired at once. “Mr. B would love that.”

“A freedom rally,” someone else agreed.

“Our own march to justice,” Tamika said, the idea taking hold. “And that’s what we’ll call it, too, but this isn’t 1965, so it’s gotta be a hashtag: #March2Justice.”

People sat up straighter, looked around at each other with excitement, and then everyone erupted in a chorus of yes, oh my God, it’s brilliant, let’s do this, let’s go.

I was caught by the idea, too, but I remember thinking: New York to Washington—that’s a lot of miles. Two hundred and fifty miles, to be exact. We did the math and figured out that if we marched for ten to twelve hours a day, it would take us nine days to cross the five states between us and the nation’s capital. Even to me, who was used to walking everywhere in the city (I didn’t have personal security concerns back then), the distance seemed crazy. We agreed we should wait till the winter weather gave way to spring, and in the meantime, we would plan the logistics and build up our physical stamina.

Mysonne Linen, a hip-hop artist who was part of our group, offered personal training classes for people up in Harlem. Since I was at the other end of the city in Brooklyn, I went out and bought a $140 treadmill and installed it in my living room the very next day. Every night, no matter how late I got home, I would walk three or four miles on that rickety machine.

We set our step-off date for April 13th, 2015. That spring would mark the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, and the 47th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. King, and yet all these years later we were still marching for the sanctity and safety of Black lives. As Carmen framed it in our official statement to the press:

The commemoration of Selma was an important and emotional occasion. We couldn’t be doing this work without the sacrifice of Congressman John Lewis and the many others who have marched and paved the way. We honor them and are grateful for their leadership. Yet while we were commemorating what happened 50 years ago, we were also reminded that Selma is now.

The people of Madison, Wisconsin, spent the same weekend mourning the death of unarmed 19-year-old Tony Robinson, who was killed by police officers. It’s important that while we remember the sacrifices made by those who marched in Selma, we ground ourselves in the reality of the times that we live in and recommit to follow in their example.

For months we met in the evenings after work to plan our agenda and itinerary for each day. We plotted our route from the southwest end of Staten Island, Eric Garner’s home, following U.S. Route 1 south all the way to the nation’s capital. I got busy working the phones to find places for us to dine and rest our heads each evening, and to have a nourishing breakfast before resuming our pilgrimage each morning. Meanwhile, Tamika reached out to affiliated community organizations, houses of worship, and college student groups, all of which pledged to help turn out participants, while Carmen worked on the messaging and press coverage.

By the end of March, almost 100 people had registered, including many 1199 union members. The head of the union, George Gresham, and Mr. Belafonte had agreed to be honorary cochairs of the march. They helped us with fundraising and sponsorships, and Mr. Gresham even secured two RVs manned by nurses and EMTs and equipped with medical supplies to accompany us along the route.

If people got blisters on their feet, they’d provide salve and a place to rest. If people’s knees or ankles ached, they’d tape us up so we could keep going. “Two hundred and fifty miles will wear on your bodies,” Mr. Belafonte had said when Carmen, Tamika, and I first met with him to tell him of our plan. “The logistics alone are crazy. But I’m on board. I don’t know what it is about you three, but I will follow you anywhere.”

On that bridge with me was every color of humanity, from all walks and experiences.

His words fortified us for the road ahead. Determined that our effort be seen as more than a publicity stunt, Carmen, Tamika, and I, as lead organizers, took pains to establish concrete goals that would yield a quantifiable result. In anticipation of the 2016 presidential campaign, which was already heating up, we partnered with local groups to help us register voters along the way.

We also planned morning and evening rallies for each day of the journey to bring awareness to the violence being done to communities of color in the name of policing. At night, we would bed down in churches, mosques, temples, schools, and community centers, and at the end of the journey, we’d gather on the lawn of the Capitol for a performance by artists who supported our cause, along with speeches by leaders in the fight for justice.

During the staged event, we would deliver to members of Congress a three-point justice package that included an End Racial Profiling Act, a Stop Militarization of Law Enforcement Act, and a Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act—each one aimed at countering the overpolicing of our neighborhoods and preserving community-based alternatives to juvenile incarceration. We’d even secured the commitment of several lawmakers in Congress to bring the proposals to the floor, where they could be debated and voted on.

Finally, everything was arranged. April 13th dawned unseasonably cool. We assembled at 9 a.m. in Staten Island, where Jumaane Williams and other city council members joined us in the parking lot of a bath and tile store for a kick-off rally. As we marched across the Outerbridge Crossing into New Jersey an hour later, we were all fired up. I surveyed our group, many holding I can’t breathe signs above their heads and chanting “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” in memory of both Eric Garner and Michael Brown.

On that bridge with me was every color of humanity, from all walks and experiences. We were Christian, Muslim, Jewish, agnostic, and atheist. We were college students, artists and musicians, PTA moms and soccer dads, ministers, city council members, attorneys, and labor unionists; people who had formerly been incarcerated; community organizers; and even a few longtime civil rights foot soldiers.

Our youngest marcher, Skylar Shafer, a white 16-year-old from Litchfield, Connecticut, had signed on to march because she was interested in advocating for children of war. Our oldest marcher, 64-year-old Bruce Richard, was an 1199 union member and former Black Panther. He’d been in the activism trenches since he was 12, when a police officer lifted him above his head and slammed him down on the hard ground because he and his cousins kept singing doo-wop songs after the officer told them to stop.

Another marcher, 22-year-old Shana Salzberg, carried as inspiration a photo of her grandfather, who had survived the Holocaust. Indeed, there were a hundred individual stories and reasons for making this pilgrimage. And every face shone bright because every person who had pulled on their walking shoes to join us that morning understood that we were marching to save lives.

__________________________________

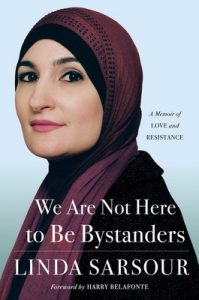

From We Are Not Here to Be Bystanders. Used with the permission of the publisher, 37 Ink. Copyright © 2020 by Linda Sarsour.

Linda Sarsour

Linda Sarsour is an award-winning civil rights activist, community organizer, and mother of three. A Palestinian Muslim American born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, she is the former executive director of the Arab American Association of New York and the cofounder of the first Muslim online organizing platform, MPower Change. She is also a founding member of Justice League NYC, a leading force of activists, artists, youth, and formerly incarcerated individuals committed to criminal justice reform through direct action and policy advocacy. We Are Not Here to Be Bystanders is available now.