How to Open a Bookstore in Rural Scotland

Learning the Hard Way Why George Orwell Disliked Being a Bookseller

FEBRUARY

Would I like to be a bookseller de métier? On the whole—in spite of my employer’s kindness to me, and some happy days I spent in the shop—no.

George Orwell, “Bookshop Memories,” London, November 1936

Orwell’s reluctance to commit to bookselling is understandable. There is a stereotype of the impatient, intolerant, antisocial proprietor—played so perfectly by Dylan Moran in Black Books—and it seems (on the whole) to be true. There are exceptions of course, and many booksellers do not conform to this type. Sadly, I do. It was not always thus, though, and before buying the shop I recall being quite amenable and friendly. The constant barrage of dull questions, the parlous finances of the business, the incessant arguments with staff and the unending, exhausting, haggling customers have reduced me to this. Would I change any of it? No.

When I first saw The Book Shop in Wigtown I was 18 years old, back in my home town and about to leave for university. I clearly remember walking past it with a friend and commenting that I was quite certain that it would be closed within the year. Twelve years later, while visiting my parents at Christmastime, I called in to see if they had a copy of Three Fevers in stock, by Leo Walmsley, and while I was talking to the owner, admitted to him that I was struggling to find a job I enjoyed. He suggested that I buy his shop since he was keen to retire. When I told him that I didn’t have any money, he replied, “You don’t need money—what do you think banks are for?” Less than a year later, on November 1, 2001, a month (to the day) after my 31st birthday, the place became mine. Before I took over, I ought perhaps to have read a piece of George Orwell’s writing published in 1936.

“Bookshop Memories” rings as true today as it did then, and sounds a salutary warning to anyone as naïve as I was that the world of selling second-hand books is not quite an idyll of sitting in an armchair by a roaring fire with your slipper-clad feet up, smoking a pipe and reading Gibbon’s Decline and Fall while a stream of charming customers engages you in intelligent conversation, before parting with fistfuls of cash. In fact, the truth could scarcely be more different. Of all his observations in that essay, Orwell’s comment that “many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop” is perhaps the most apposite.

Orwell worked part-time in Booklover’s Corner in Hampstead while he was working on Keep the Aspidistra Flying, between 1934 and 1936. His friend Jon Kimche described him as appearing to resent selling anything to anyone—a sentiment with which many booksellers will doubtless be familiar. By way of illustration of the similarities—and often the differences—between bookshop life today and in Orwell’s time, each month here begins with an extract from “Bookshop Memories.”

The Wigtown of my childhood was a busy place. My two younger sisters and I grew up on a small farm about a mile from the town, and it seemed to us like a thriving metropolis when compared with the farm’s flat, sheep-spotted, salt-marsh fields. It is home to just under a thousand people and is in Galloway, the forgotten southwest corner of Scotland. Wigtown is set into a landscape of rolling drumlins on a peninsula known as the Machars (from the Gaelic word machair, meaning fertile, low-lying grassland) and is contained by 40 miles of coastline which incorporates everything from sandy beaches to high cliffs and caves. To the north lie the Galloway Hills, a beautiful, near-empty wilderness through which winds the Southern Upland Way. The town is dominated by the County Buildings, an imposing hôtel-de-ville-style town hall which was once the municipal headquarters of what is known locally as “the Shire.” The economy of Wigtown was for many years sustained by a Co-operative Society creamery and Scotland’s most southerly whisky distillery, Bladnoch, which between them accounted for a large number of the working population. Back then, agriculture provided far more opportunities for the farm worker than it does today, so there was employment in and about the town. The creamery closed in 1989 with the loss of 143 jobs; the distillery—founded in 1817—closed in 1993. The impact on the town was transformative. Where there had been an ironmonger, a greengrocer, a gift shop, a shoe shop, a sweet shop and a hotel, instead there were now closed doors and boarded-up windows.

“There is a stereotype of the impatient, intolerant, antisocial proprietor and it seems (on the whole) to be true. There are exceptions of course, and many booksellers do not conform to this type. Sadly, I do.”

Now, though, a degree of prosperity has returned, and with it a sense of optimism. The vacant buildings of the creamery have slowly been taken over by small businesses: a blacksmith, a recording studio and a stovemaker now occupy much of it. The distillery re-opened for production on a small scale in 2000 under the enthusiastic custody of Raymond Armstrong, a businessman from Northern Ireland. Wigtown too has seen a favorable change in its fortunes, and is now home to a community of bookshops and booksellers. The once boarded-up windows and doors are open again, and behind them small businesses thrive.

Everyone who has worked in the shop has commented that customer interactions throw up more than enough material to write a book—Jen Campbell’s Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops is evidence enough of this—so, afflicted with a dreadful memory, I began to write things down as they happened in the shop as an aide-mémoire to help me possibly write something in the future. If the start date seems arbitrary, that’s because it is. It just happened to occur to me to begin doing this on February 5, and the aide-mémoire became a diary.

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 5

Online orders: 5

Books found: 5

Telephone call at 9.25 am from a man in the south of England who is considering buying a bookshop in Scotland. He was curious to know how to value the stock of a bookshop with 20,000 books. Avoiding the obvious answer of “ARE YOU INSANE?,” I asked him what the current owner had suggested. She had told him that the average price of a book in her shop was £6 and that she suggested dividing that total of £120,000 by three. I told him that he should divide it by ten at the very least, and probably by 30. Shifting bulk quantities these days is near impossible as so few people are prepared to take on large numbers of books, and the few that do pay an absolute pittance. Bookshops are now scarce, and stock is plentiful. It is a buyer’s market. Even when things were good back in 2001—the year I bought the shop—the previous owner valued the stock of 100,000 books at £30,000.

Perhaps I ought to have advised the man on the telephone to read (along with Orwell’s “Bookshop Memories”) William Y. Darling’s extraordinary The Bankrupt Bookseller Speaks Again before he committed to buying the shop. Both are works that aspirant booksellers would be well advised to read. Darling was not in fact The Bankrupt Bookseller but an Edinburgh draper who perpetrated the utterly convincing hoax that such a person did indeed exist. The detail is uncannily precise. Darling’s fictitious bookseller—”untidy, unhealthy, to the casual, an uninteresting human figure but still, when roused, one who can mouth things about books as eloquently as any”—is as accurate a portrait of a second-hand bookseller as any.

Nicky was working in the shop today. The business can no longer afford to support any full-time staff, particularly in the long, cold winters, and I am reliant on Nicky—who is as capable as she is eccentric—to cover the shop two days a week so that I can go out buying or do other work. She is in her late forties, and has two grown-up sons. She lives in a croft overlooking Luce Bay, about 15 miles from Wigtown, and is one of Jehovah’s Witnesses, and that—along with her hobby of making strangely useless “craft” objects—defines her. She makes many of her own clothes and is as frugal as a miser, although extremely generous with what little she has. Every Friday she brings me a treat that she has found in the skip behind Morrisons supermarket in Stranraer the previous night, after her meeting at Kingdom Hall. She calls this “Foodie Friday.” Her sons describe her as a “slovenly gypsy,” but she is as much part of the fabric of the shop as the books, and the place would lose a large part of its charm without her. Although it wasn’t a Friday today, she brought in some revolting food which she had pillaged from the Morrisons skip: a packet of samosas that had become so soggy that they were barely identifiable as such. Rushing in from the driving rain, she thrust it in my face and said “Eh, look at that—samosas. Lovely,” then proceeded to eat one of them, dropping sludgy bits of it over the floor and the counter. During the summers I take on students—one or two. It allows me the freedom to indulge in some of the activities that make living in Galloway so idyllic. The writer Ian Niall once wrote that as a child at Sunday school he was convinced that the “land of milk and honey” to which the teacher referred was Galloway—in part because there was always an abundance of both in the pantry of the farmhouse in which he grew up, but also because, for him, it was a kind of paradise. I share his love of the place. These girls who work in the shop afford me the luxury of being able to pick my moment to go fishing or hill-walking or swimming. Nicky refers to them as my “wee pets.”

The first customer (at 10.30 am) was one of our few regulars: Mr Deacon. He is a well-spoken man in his mid-fifties with the customary waistline that accompanies inactive middle-aged men; his dark, thinning hair is combed over his pate in the unconvincing way that some balding men try to persuade others that they still retain a luxuriant mane. He is smartly enough dressed inasmuch as his clothes are clearly well cut, but he does not wear them well: there is little attention to detail such as shirt tails, buttons or flies. It appears as though someone has loaded his clothes into a cannon and fired them at him, and however they have landed upon him they have stuck. In many ways he is the ideal customer; he never browses and only ever comes in when he knows exactly what he wants. His request is usually accompanied by a cut-out review of the book from The Times, which he presents to whichever of us happens to be at the counter. His language is curt and precise, and he never engages in small talk but is never rude and always pays for his books on collection. Beyond this, I know nothing about him, not even his first name. In fact, I often wonder why he orders books through me when he could so easily do so on Amazon. Perhaps he does not own a computer. Perhaps he does not want one. Or perhaps he is one of the dying breed who understand that, if they want bookshops to survive, they have to support them.

At noon a woman in combat trousers and a beret came to the counter with six books, including two nearly new, expensive art books in pristine condition. The total for the books came to £38; she asked for a discount, and when I told her that she could have them for £35, she replied, “Can’t you do them for £30?” It weighs heavily upon my faith in human decency when customers—offered a discount on products that are already a fraction of their original cover price—feel entitled to demand almost 30 percent further off, so I refused to discount them any further. She paid the £35. Janet Street-Porter’s suggestion that anyone wearing combat trousers should be forcibly parachuted into a demilitarized zone now has my full support.

Till total £274.09[*]

27 customers

[*] This figure does not take into account our online sales, the money for which Amazon deposits into the shop’s bank account every fortnight. Online turnover is considerably less than that of the shop, averaging £42 per day. Since 2001, when I bought the shop, there have been tectonic shifts in the book trade, to which we have had no choice but to adapt. Back then online selling was in its relative infancy, and AbeBooks was the only real player for second-hand books; Amazon at that point sold only new books. Because AbeBooks was set up by booksellers, the costs were kept as low as possible. It was a very good means of selling more expensive books—the sort that might have otherwise been hard to sell in the shop—and because there were relatively few of us selling through it back then, we could realize pretty decent prices. Now, of course, Amazon is consuming everything in its path. It has even consumed AbeBooks, taking it over in 2008, and the online market-place is now saturated with books, both real and electronic. Yet we have no real alternative but to use Amazon and AbeBooks through which to sell our stock online, so reluctantly we do. Competition has driven prices to a point at which online bookselling is reduced to either a hobby or a big industry dominated by a few huge players with vast warehouses and heavily discounted postal contracts. The economies of scale make it impossible for the small or medium-sized business to compete. At the heart of it all is Amazon, and while it would be unfair to lay all the woes of the industry at Amazon’s feet, there can be no doubt that it has changed things for everyone. Jeff Bezos did not register the domain name “relentless.com” without reason. The total for the number of customers may also be misleading—it is not representative of footfall, merely of the number of customers who buy books. Normally, the footfall is around five times the figure for the number who buy.

__________________________________

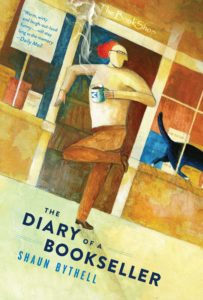

From The Diary Of A Bookseller. Courtesy of Melville House Books. Copyright © Shaun Bythell.

Shaun Bythell

Shaun Bythell has run The Bookshop in Wigtown since November 1, 2001. His internationally bestselling books The Diary of a Bookseller, Confessions of a Bookseller, and Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops have been translated into over twenty languages. His latest book is Remainders of the Day. His passion for bookselling is matched only by his sense of despair for its future.