How to Keep Track of Your Characters With Index Cards, String, and a Lot of Clothes Pins

Rebecca Sacks on Managing a Cast of Dozens of Imaginary People

My first novel, City of A Thousand Gates follows the intersecting lives of dozens of characters in the wake of ethnic violence in Jerusalem and on the West Bank. Following multiple points of view wasn’t just a narrative tactic but an ethical imperative. The conflict between Israel and Palestine is one that has bred deeply contradictory truths that should, I suppose, cancel each other out, but instead create a paradox that feels truer than any one narrative.

Keeping track of a cast of over 29 characters, dozens of points of view, intertwined narratives, and competing versions of the same events was complicated and demanding. How to keep all the narratives clear in my own head? How to ensure the various timelines were consistent? How to detect places where characters’ stories might overlap? How to submerge fully into each point of view while keeping track of these larger-order concerns? The answer: it required a lot of clothespins and index cards.

To attend to the logistical demands of this undertaking, while also finding joy in the intensity of it all, I made the process as physical as possible. My goal as a writer is to spend as little time as possible in front of my computer. I try to compose initial drafts longhand; I print typed drafts and edit with a pen. I want the work to feel beautiful and idiosyncratic; I want to be overwhelmed, because for me, that’s the greatest pleasure of all.

A typical editing day with my officemate, Pupik.

A typical editing day with my officemate, Pupik.

Index cards pinned to a corkboard were my primary way of tracking the sequence of chapters, which was constantly shifting because I did not write this book in anything approaching chronological order. Index cards were especially helpful in charting outside events in relation to the private lives of characters. By outside events I mean collective experiences, for example, the changing of the seasons, religious holidays, the political violence unfolding throughout the book, the development of a news story that several of the characters are following. I wish I’d taken photos of my corkboard at its most unhinged. At the time, so much of what I was doing was a secret even from myself. I documented so little. However, in the right-hand corner of this photo of my room from about 2018, you can see the blue index cards on the corkboard; each of them is the title of a chapter and, to the left, are major events detailed on white index cards.

Index cards gave me an overview of the novel.

Index cards gave me an overview of the novel.

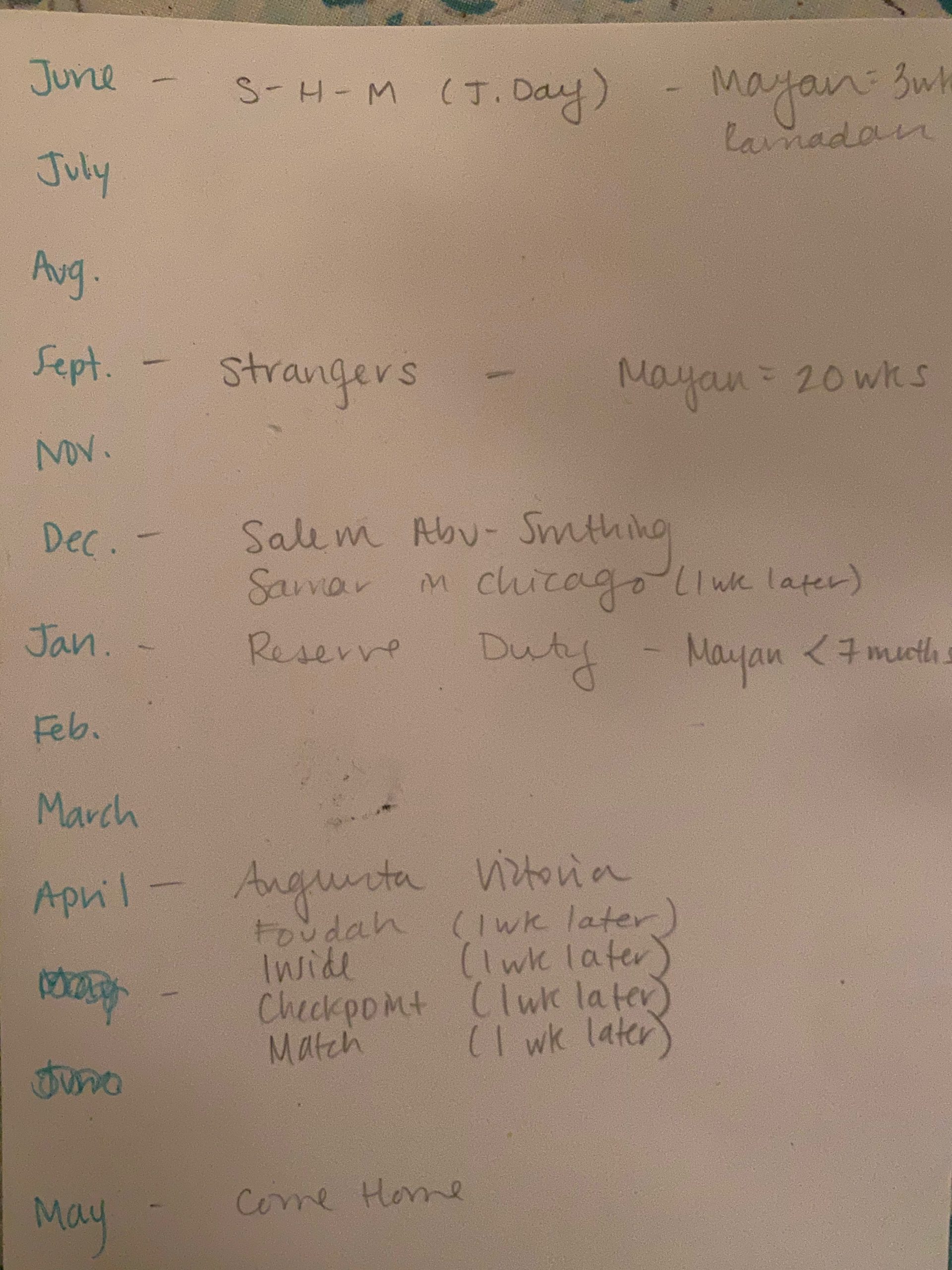

For me, it was important to have temporal information on hand, even if very little of this information was explicitly given to readers. For example, in the opening chapter of the novel, we meet a couple and their newborn, Mayan; the novel unfolds over the course of just under one year, so Mayan’s development is a kind of “clock” for the novel, because of how drastic development is that first year. (I don’t have children. I read a lot of parenting blogs to glean this.) Not only did I need to know Mayan’s age in weeks each time one of her parents had a chapter in their point of view, but I also needed to know how old Mayan was at each important event of the novel. So, for example, when in a later chapter of the novel, Mayan’s mother is remembering where she was when a big news story broke, I needed to know Mayan’s exact age to be able to say for sure that the night the young Palestinian boy’s corpse was smuggled from the hospital, Mayan had not yet begun to walk. Here is an obsolete attempt to chart Mayan’s age against the unfolding months of the novel and the chapters I had at the time:

A preliminary attempt to track the newborn Mayan’s age. This notecard was one of many pinned to my corkboard for easy reference. It was soon replaced, as the entire novel timeline ended up changing considerably to make all the timelines work together.

A preliminary attempt to track the newborn Mayan’s age. This notecard was one of many pinned to my corkboard for easy reference. It was soon replaced, as the entire novel timeline ended up changing considerably to make all the timelines work together.

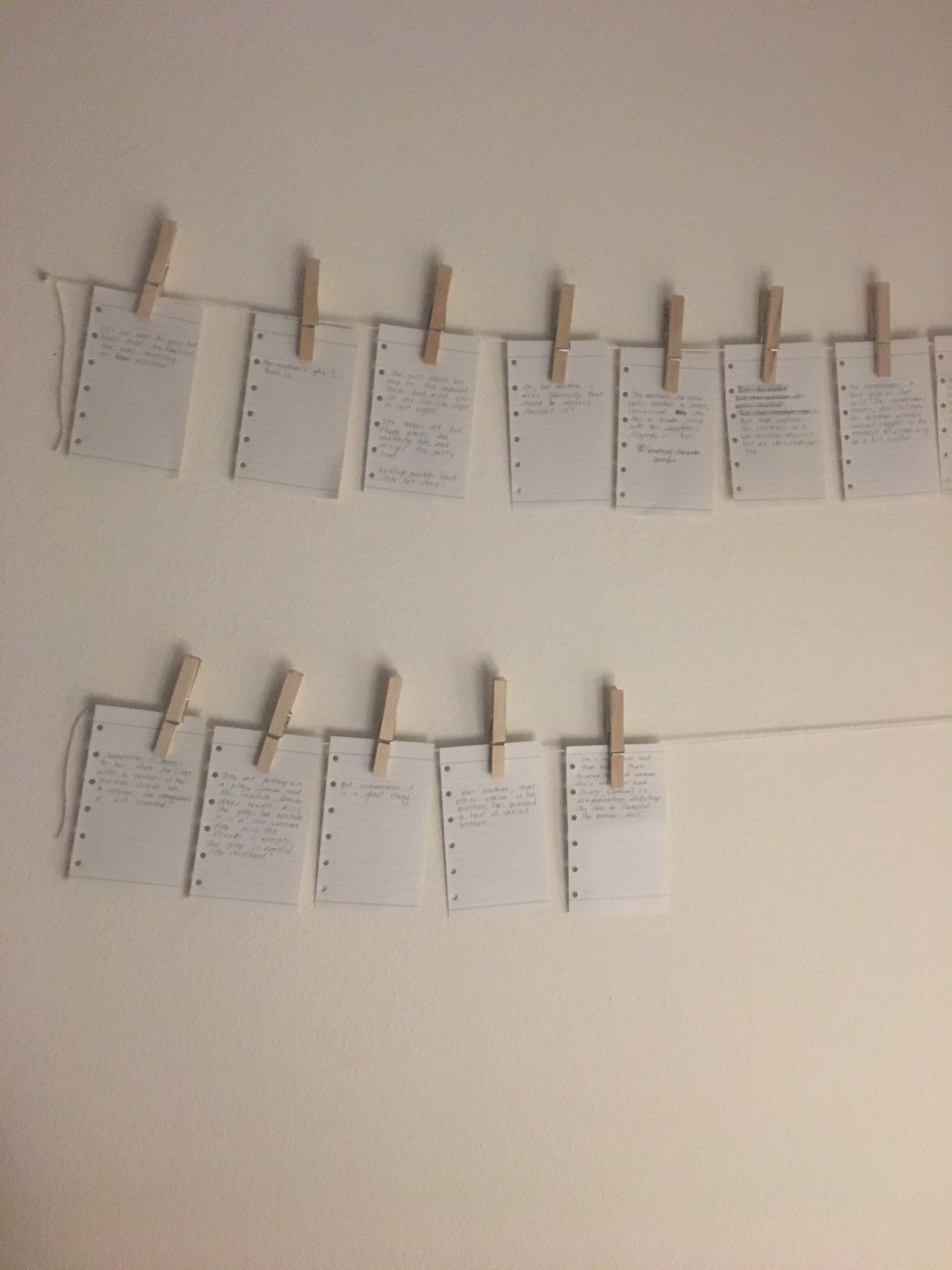

Every room I’ve lived in since 2015 has had walls dominated by lines of twine and affixed with miniature clothespins. This is how I compose and edit. It makes me look like detective descending into madness as she solves a particularly twee mystery, but it’s worth it.

If you run out of the mini clothespins, full-sized will do!

If you run out of the mini clothespins, full-sized will do!

Allowing myself the freedom to get lost inside a chapter, as opposed to worrying how that chapter would work with the other events of the book, became harder and harder as the novel took shape. I found myself relying on my system of twine and clothespins to help me immerse myself fully in the work: sentence by sentence. I use this method to compose and to edit. For composition, I write my earliest drafts on small sheets of paper intended for a day planner. These sheets are still part of my composition process, even as I begin a new project. They are perfect: small, light, lined, and elegant.

This company should sponsor me.

This company should sponsor me.

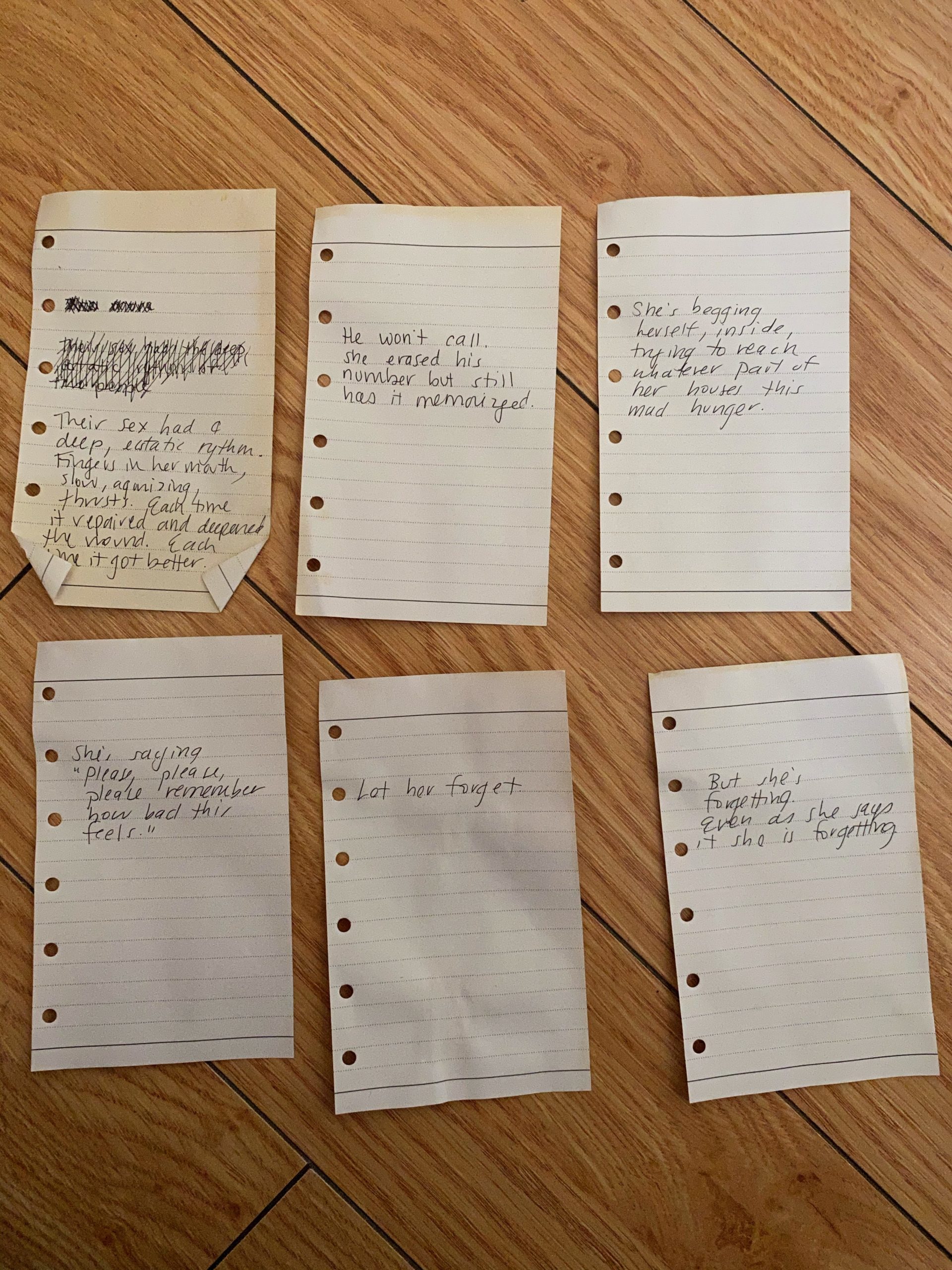

Lined sheets in early chapter draft, circa 2016.

Lined sheets in early chapter draft, circa 2016.

I began each chapter by listening for sentences from deep inside the point of view of the character I’d be narrating from. I wrote each sentence on one of the lined sheets. It did not matter if there was not yet a sense of narrative or even a fully fleshed out character. I affixed each sheet to the wall; I put them in conversation with one another.

I have a tendency to rush through my narration, especially when I know where I want a chapter to end up. With the writing on the wall (forgive me), I found I could detect places where I could linger, fill in the sentences between slips of paper. I found the sentences—paragraphs, even—required to connect one sentence to another. I wrote each one on its own sheet of paper, and affixed it on the line where it belonged. In this way, the composition process was not linear at all, but more like the slow emergence of a sculpture or birdsnest.

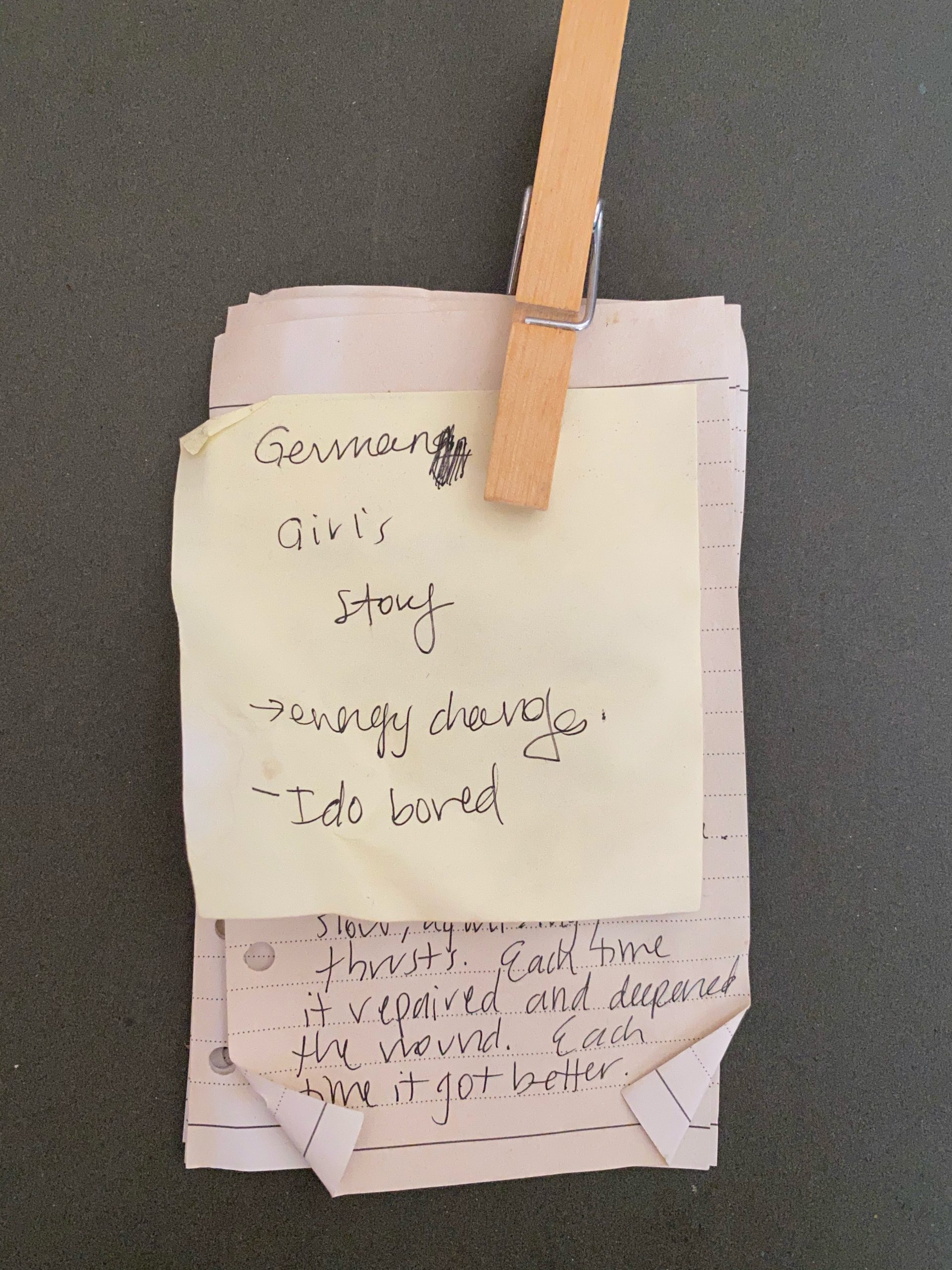

Hanging the work up on the wall and stepping back from it also allowed me to see where chapters touched: when were characters in the same place, and might describe the same event differently in their respective chapters? When might I pick up the narrative of a side character from one chapter and, perhaps, give her a chapter of her own? This is exactly what happened in the case of a character who first appeared to me as a nameless German hitchhiker that Emily and Ido (parents to the novel’s newborn, Mayan) pick up on a tense weekend away. The more I wrote, the more invested I became in this strange hitchhiker. Eventually, I realized that she needed her own chapter. Below are the sheets I pulled from the chapter in which the German hitchhiker was a supporting character in order to begin a new chapter from her point of view. She became one of the novel’s central characters.

When I pulled these sheets, I did not even know the character’s name.

When I pulled these sheets, I did not even know the character’s name.

Initial sentences from the POV of the then-unnamed German hitchhiker. A few of these lines made it into the book.

Initial sentences from the POV of the then-unnamed German hitchhiker. A few of these lines made it into the book.

As well as generating sentences, this system is—in my humble but tested opinion—the best way to edit a chapter once it’s been drafted on the computer and printed. My approach was to cut out every paragraph and pin it up with a miniature clothespin. Not only did this offer me another opportunity to see space between paragraphs—places where I might dig deeper in—but also to get a sense of how much space each thread, or concern driving a character’s narrative, was given in a story.

An early draft of the chapter “Strangers” up on the wall. A sidenote: If you can’t make holes in your wall, a nice alternative is using masking tape to hold up your papers. I do that when I’m traveling.

An early draft of the chapter “Strangers” up on the wall. A sidenote: If you can’t make holes in your wall, a nice alternative is using masking tape to hold up your papers. I do that when I’m traveling.

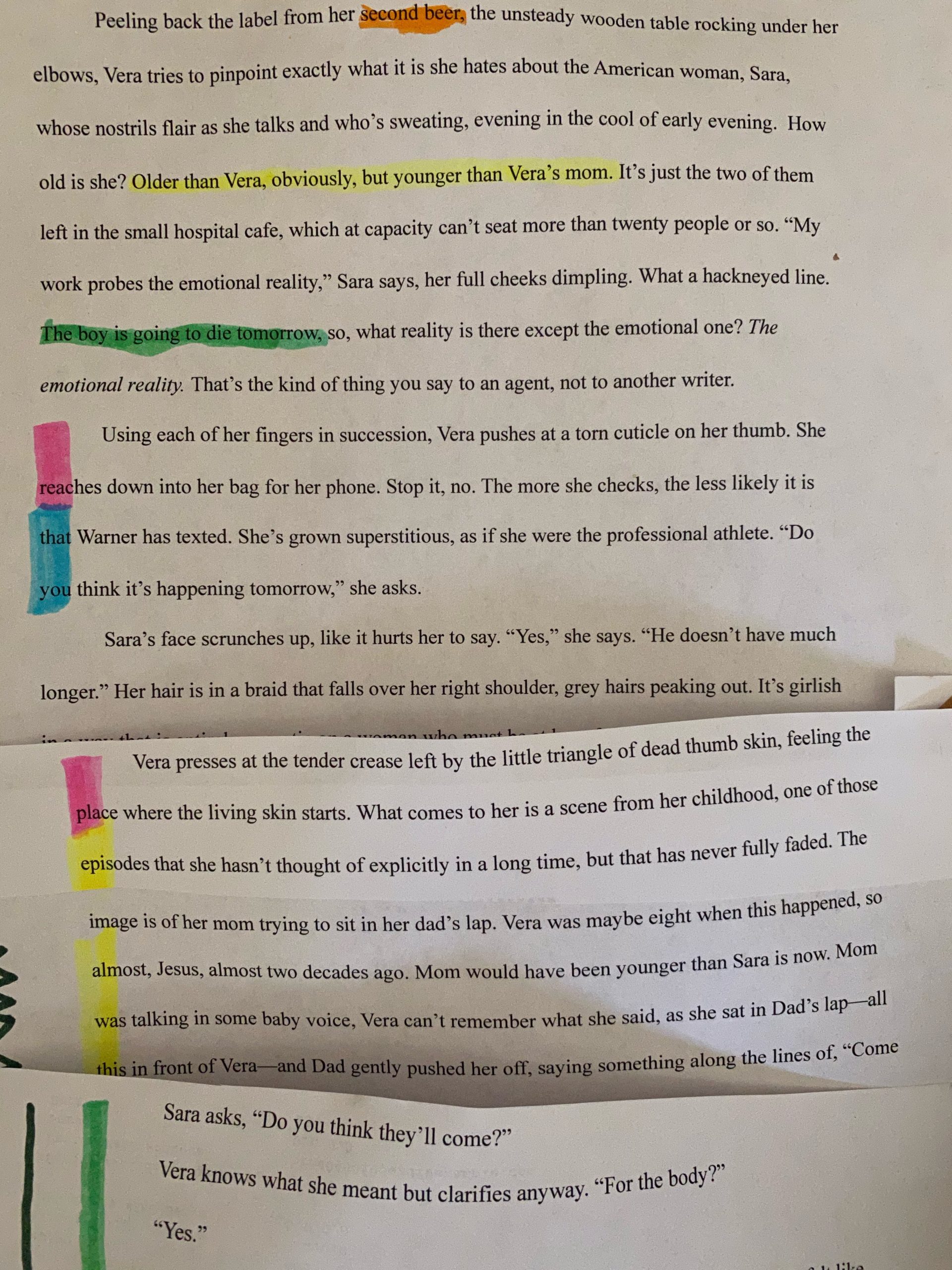

Here is a close up of a draft of the chapter I eventually wrote from the point of view of the German hitchhiker who, it turned out, was a journalist who has come to the West Bank to make her name in tragedy:

In this draft, I assigned a highlighter color to each of the threads I wanted to attend to in this chapter: Vera’s self-destruction is in pink; her obsession with an Israeli fuckboy is in blue; shameful memories of her mother are in yellow; the concern of the day (an unfolding news story that Vera and another journalist are competing over) is in green; I track her beers in orange so I know how drunk to make her. Each of these paragraphs was hanging up across my room’s clotheslines. As a result, I could stand back and understand how the concerns of the story are weighted in the story, not by reading, but by the placement of colors.

This was also a way for me to confirm that the threads of a chapter come into play early enough. My general sense is that about one-fourth through a chapter, I want all the factors to be introduced. I don’t stick to this as a rule, but if I’m going to introduce a new element on page 20 of a 25-page chapter, I’d prefer to have a justifiable reason, e.g., deliberately subverting the anticipated shape of the narrative.

I have four bankers boxes filled with this sort of thing.

I have four bankers boxes filled with this sort of thing.

For many of the years I was writing this novel, my mattress was on the floor. I slept in the room I wrote in. I went to bed in a room like a spider web, surrounded by bits of chapters dangling over me and around me. I woke up that way, too—as if I was waking up into my own book, my own mind. The intensity was hard to bear. I miss it.

All that remains.

All that remains.

_________________________________________

Rebecca Sacks’ City of a Thousand Gates is available via Harper.

Bee Sacks

Bee Sacks (they/them) holds an MFA from the Programs in Writing at the University of California, Irvine. Their debut novel, City of a Thousand Gates, was awarded the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for fiction in 2023. A former journalist, they worked at Vanity Fair for several years before moving to Israel/Palestine to study sacred Jewish texts. Bee now lives in Los Angeles with their dog, Pupik.