How to Fictionalize New Technology Even As It’s Constantly Changing

Claire Stanford on a Novelist's Approach to Tech

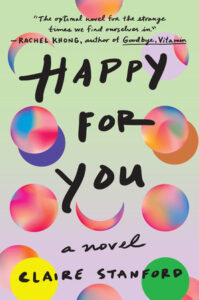

When I started writing what would become my debut novel, Happy for You, in 2015, the Cambridge Analytica scandal had not yet happened. I wanted to write about technology—specifically, internet technology—which, at the time, was still awash in techno-optimism, but which I was beginning to suspect was having some negative effects on my brain, on my sense of being. A story started to emerge: a woman in her early thirties leaves a PhD program in philosophy for the glittering world of tech—a job at the third-most-popular internet company. There, her team is tasked with developing an app that measures user happiness—an idea that, seven years ago, felt thoroughly speculative.

Immersed in building a character and a voice and a narrative arc that showed how the experience of trying to quantify emotions had changed the narrator, I didn’t think much about the fact that the technology itself would hardly stay static over the several years required to write a novel. Which led to a craft question I had not previously considered: How do you write about a subject—in my case, technology—that is constantly changing?

As I came to realize, this was a two-fold problem. First, there was the actual hardware and software that was always advancing. When I began writing, I thought I was writing about a futuristic technology—an app that attempted, through a series of biometrics and user surveys, to assess one’s emotions; now, while the technology is not quite as advanced as in my novel, these kinds of apps are more or less reality. And second, there was the ever-developing political context of internet technology, which, as I was writing, rapidly moved from personally unsettling to geopolitically destabilizing.

Some of the tech went through multiple iterations. In one chapter, the narrator encounters a new form of advertising called Adapt—individualized ads that pop up on bus shelters, activated by a users’ cell phone. Originally, I had envisioned Adapt as embedded in individual sidewalk squares (in these drafts, it was called AdWalk); when I was a child, I had been mesmerized by the glitter (literal glitter) embedded in the sidewalk squares in some parts of San Francisco, and AdWalk was a play on that. But as the rest of my novel became less and less speculative, the sidewalk-square version of AdWalk-Adapt was an oddly futuristic detail that had to be toned down.

A novel isn’t an iPhone or an app. You can’t keep releasing a newer version, or a software patch.More complex was building the app, JOYFULL, itself. Recently, going through some old notes, I encountered a scribble from what must have been extremely early on in the writing process: What if JOYFULL wasn’t a finished app, but was in process? This decision—to make the app in development rather than fully existing out in the world—was one of the keys to writing about the technology. An app in development could be imperfect; an app in development could have glitches. Still, JOYFULL had to keep changing to stay one step ahead of the real world. I read about neural networks and artificial intelligence, I listened to podcasts about whether your phone (read: Facebook) is spying on you and about “raising” an artificial intelligence, I tested out apps with biometrics and thought about how I could make them yet a little more invasive.

I began to think of the app as a character in its own right, one with its own distinct voice and its own slant on the world. Thinking of the app as its own character freed me from trying to mimic existing technology—trying to channel Siri or Alexa. Instead, as I was writing, I realized that the app could say anything I wanted it to say. I began to put the app in conversation with Evelyn, the narrator, asking her questions that dwelled in her subconscious but that she—without the prodding of the app—didn’t want to look at straight on. DO YOU THINK YOUR PARENT(S) ARE PROUD OF YOU?, it asked. DO YOU EVER FEEL LIKE YOU ARE ALL ALONE? By giving the app its own individuality, it began to matter less what else was happening in hardware and software developments; this was the way JOYFULL spoke, this was the way JOYFULL thought.

The other key was the character of Evelyn herself. Evelyn is a philosopher, not an engineer; she is confused and sometimes overwhelmed by the Silicon Valley world she finds herself in. In the early false starts of the novel, the narrator was, first, a scientist who developed the technology to measure emotions, and, second, the scientist’s assistant. Neither of these narrators took the book very far. I realized what I wanted for a narrator was not an insider but an outsider. Someone who was trying to understand not only the technology but the tech ethos; someone who—for a myriad of reasons, primarily financial—wanted to believe in the company’s mission, but couldn’t bring herself to get fully on board.

As I wrote, the world’s view of technology was changing. There was the 2016 election and the Cambridge Analytica scandal, there was the growing awareness of algorithmic bias and its effects on women and people of color, and there was the increasing cynicism about the way social media companies buy and sell our data—the way they buy and sell aspects of our lives. Focusing on Evelyn’s experience—on the personal—was also my way of accessing the larger political questions around contemporary technology. I didn’t want the novel to be didactic; rather, I wanted to explore how one person, Evelyn, is affected by these increasingly-invasive technologies, and how she attempts to justify that work. She is conflicted, she is confused; she is sometimes bemused and sometimes repulsed by the ongoing march of technology into our private lives, its commodification of the self.

Even as the novel’s plot is framed around the happiness app and the third-most-popular internet company, really, the book is about Evelyn as a character. Technology exacerbates the questions she has about her life—about marriage, and motherhood, and the general confusion of being a person in the world—but it is not, ultimately, the central point of the book. Still, throughout the years of working on my novel, and especially toward the end, as it neared its finalized state, something I grappled with was the urge to keep updating, keep adding, keep iterating.

But a novel isn’t an iPhone or an app. You can’t keep releasing a newer version, or a software patch. Part of the beauty of a novel is that it is a window into the mind of a single person—the writer—at a specific moment in time. The political situation around technology will keep changing, and so will the technology itself. But the core questions of the book, the questions foremost on my mind as I was writing it—how does a person find their place in the world? how do they strike out on their own path?—are perennial, questions that existed long before apps and wearables and social media, and questions that will exist, I hope, long after.

__________________________________

Happy for You by Claire Stanford is available via Viking.