My sister, Agatha Krishna, said it started when they came, and so that’s where you could put the blame. But then she said we had to go further back than that. So we blamed it on Reagan; everyone blamed him that summer, the summer the country went into a bust, the summer we watched an exodus empty our town. Then I blamed the Cold War, and Gorbachev—he had the stain on his head, and thus, I felt, couldn’t be trusted. We blamed famine in Ethiopia after Amma posted a photo on the fridge of a child with a belly like a hot-air balloon. We blamed AIDS, which we didn’t really get, but thought you could get from the water fountain at the public library you stepped on with your foot. We blamed the Olympics and hated Sam the eagle, their feathered mascot, who dressed like Uncle Sam in red, white, and blue, though secretly I had a button of him with his sly smile and torch. We blamed it on my parents for moving to Wyoming in the first place, for settling in Marley. Then we just generally blamed them for everything. We thought they shouldn’t have married, that they shouldn’t have mixed us up. Shouldn’t have made us halfies. Agatha Krishna said we could blame it on our grandparents too, for having one child who went to school and another who stayed at home. For letting Amma wear a crisp, white uniform and leaving Vinny Uncle to read Curly Wee comics.

But then she said, “Let’s blame it on the British.” Everything went back to the British. They did it first, Agatha Krishna said. They were colonists. They were the reason our amma went to school and our uncle stayed home; they were the reason that we were quiet around most white people, the reason our mom drank tea when everyone else we knew, except Mormons, drank coffee. It was the British who shaped Amma’s world. That made her spell favor with a u, use a knife and fork, and bake fruitcake with sultanas and nuts. It was the British who taught us to keep our upper lips stiff at all times.

That year, we had an Indian summer twice. A frost had come and left the garden in disarray. Tomato stalks broke in two, my mother’s peppers dangled like limp green earrings from the stem. But then the days warmed again and an infestation of millers descended.

They threw themselves in swarms at the streetlights, marking the intersections. They offered a kind of suttee to the light. Black dots against the Krishna-colored sky. My father, tired from corning off rigs, would fill a large stainless steel bowl with dish soap at night. Leaving it on his desk, he would shine a desk lamp into the soapy bowl. By morning, the bubbles would long have gone flat and the little bodies of the millers would be floating in the water, their wings soaked and black.

I always felt bad for them. Drawn to something beautiful, something almost ethereal, only to find themselves trapped. I didn’t think it was a good way to die. But what is? And the only way you could justify it was when Arnrna held up saris eaten to lace, sweaters with holes the size of coins.

Years later, I would learn that miller moths don’t eat clothes. They’re actually great pollinators. We were wrong. Small clothes moths are the real pests. Clothes moths barely fly and don’t like the light. But Appa didn’t like the sound of the millers hitting the lights at night. Of them clogging the sills of our doors and windows with their downy scales.

It was in that second wave of warmth that they came to us. Not tired or wretched or tempest-tossed, but poor. We drove to Denver to pick them up. They did not come off the plane looking bewildered by this new land before them. If anything, they came at us like moths. Fast, a little frantic, and seemingly, as the months would show, drawn to all the wrong things.

Amma, who had not seen a member of her family since marrying my father almost fourteen years earlier, ran to her brother, Vinny Uncle, pressed a carton of Marlboro Reds into his pocket, then squeezed my cousin Narayan like a lemon and filled his hands with chocolate. She gave Auntie Devi a rhinestone necklace. We piled into two cars to drive home. Narayan screamed when he saw his first antelope. Auntie Devi stuck her head out the window to catch the wind. Vinny Uncle just remarked on how fast the car went. That we didn’t have to stop for animals in the road or pause at scooters packed with bodies.

The Ayyars dipped into our lives like a tea bag into the whiteness of a porcelain cup. They muddied the water and made our house feel small, having taken over Agatha Krishna’s old bedroom. Now she slept with me. They left rings of talcum powder on the carpet; the bathroom :floor was slick with water from their cup and bucket, and the house became smelly with the food Auntie Devi cooked: dosas and sambar, prawns fry and molee. If she wasn’t cooking, she stood on the lawn in a sari and cardigan, looking out at nothing. Feeling the air and the altitude with a kind of wonder. Or sometimes she sat in front of the television. She watched a lot of Dynasty. She no longer had her own house; she didn’t drive. She had to ask Amma to buy her everything, from underwear to airmail paper. To us, she said little, just cooked us food, then slipped back to the bedroom to watch TV late into the night. She was like Amma. Same long black hair. But not Amma. She was ghost-Amma. The Amma who didn’t say anything. The Amma in the room who faded into the furniture. As if she had only half come to America.

When you really came down to it, we blamed our uncle. And no matter who started it, we were the ones who had to finish it. So at night, as we lay in bed, Agatha Krishna in a sleeping bag zipped tight to her head, and me under a blanket half-eaten by moths, we told ourselves that it wasn’t our fault. She sang a mantra: “The British are to blame, the British are to blame, the British are to blame, and Vinny Uncle will pay.” And soon, I joined her. We would make him pay.

Looking back, though, I’m not sure if that’s how it works. I’m not sure you can ever cancel out someone who has taken from you by taking more from someone else. But I think that was the only way we could do it, the only way we could have killed him. The only way we could take our uncle’s life and not look back. Not be filled with any blame.

*

But.

But before I give you that, before I tell you what happened, I have to give you this.

Because you ask for it, I give it to you.

Because you don’t ask for it, I give it to you.

Because you always seem to want to take what I give you and translate it into something else, something that fits your narrative, you can have it.

Let’s just say it. This story is for you; I know you want it to go a certain way.

I get it. We all do. And don’t worry, I’ll give you that story. But before we go back, before I tell you about the murder, about that year, I’ll tell you this, just to get it out of the way. Here is what you want. Here it is as a list, so organized, so efficient:

1. I am going to give you mangoes. Fat, green globes of fruit. Green, because they are picked too early and sent to Wyoming with only a hint of blush. These mangoes show up a few times a year. They are from Mexico, their taste a kind of thready sweetness, but my mother buys them anyway. We don’t all like to eat mangoes. They’re a heaty food, and my mother (Amma, Amma, Amma) makes us drink a large glass of milk an hour after we’ve had one to offset the heat she thinks will build in our stomachs. I hate milk. But when she serves us slices of mango with Tang, it’s as if we’re eating fire. She will chew on the seed for hours. Ripping off every piece of the flesh, the fibrous pit like a heart in her hand. She buries the seeds in pots, and we wait for a mango tree to bloom. It will not grow, even as Agatha Krishna and I grow other things—crystals for a science project, sprouts in a two-liter pop bottle that becomes a mini greenhouse-earning each of us a Girl Scout badge. But the mango never does. And yet somehow, there are always more mangoes. All the superstores have them. Now we can get them at Target, make eye contact with the other others as we reach for the fruit, as we squeeze the skin, as we wonder what the flesh is like, under that taut, green skin.

2. Only Aunt Devi wears sans. Sorry. Amma gave them up years ago. She wears jeans and sweaters. When the Ayyars arrived, she wore saris again for a bit. But usually, they just sit on the top shelf of her closet, stacked one on top of another. Occasionally, one slides to the floor, the slipperiness of silk on silk, a pool of gold and incandescence on the carpet. Months after the Ayyars moved in, Amma and Aunt Devi went to JoAnn Fabrics to look through the bolts of fabric. I do not wear Indian clothes. Not because I don’t want to, but because there is nowhere to buy a pavada, so I wear my own dresses to Indian functions. I don’t like playing dress-up. I, who was soon to lose interest in Girl Scouts in favor of joining 4-H in the fall, would enter the fair with cotton Butterick dresses the following summer. I delighted in calico and sprigged lawn, neither of which hang well enough for a sari. I wanted to make a dove-in-the-window quilt like Laura Ingalls. But Amma and Aunt Devi bought six yards of various rayons. Unlike calico and sprigged lawn, rayon hangs well. They’d pull cholis out of their bags and match the spray of a tulip or the stem of a daisy to them. “Lots of fabric!” the lady at JoAnn would say. “Yes,” said my mother. “There’s so much to cover.” It was true—sometimes we used Amma’s saris to make a fort.

3. All the spices. All the food. You want this the most. And yet, there was nothing magical about our meals. When my dad was on a rig, we often ate ramen, or bread with deviled ham. But sure, there was plenty of Indian food too. Dosas with ghee and sugar for breakfast, rasam when I had a cold, which Amma would make me drink from a small steel cup, one night’s leftover rice turned to the next day’s curd rice, dal that sat on the stove for days, never refrigerated, and curries. Lots of curries. We drove to Denver every so often to buy our spices. My job was to use the mortar and pestle to pound down garlic and ginger. My hands always smelled of somewhere else. When I went to Camp Sacajawea, which is now Camp Sacagawea, my mother tucked a jar with a tablespoon of curry powder inside my sleeping bag. She knew I would be homesick. Brushing my teeth by the small outdoor sinks, I’d dab some up my nose. To smell her, to smell home.

4. Wild We did not have tigers. There were no elephants. But there was a small museum in town of one man’s taxidermy collection. He’d shot a lot of African animals. Zebras, warthogs, antelopes with horns that looked like long, twisted lollipops. At one point he took to hunting in colder climes. A polar bear in an angry pose and an arctic fox graced a room that also held a walrus. This man, this rancher, shot everything, from elk to coyotes. We knew that outside of town, and on the foothills of Marley Mountain, there were herds of antelope and deer. Occasionally there would be a rumor of a bear roaming around on the mountain. Campers would come out to find slashes in their duffels, pillowy bags of chips and coolers full of hot dogs gone. When Appa was home, he read us The Jungle Book at night, and we wondered which was more dangerous, a rattlesnake or Kaa.

5. We weren’t poor. We weren’t rich. We were dependent on the price of oil. The Ayyars were beholden. But none of us was worse off than the boy on the fridge. The boy from Ethiopia, whose wide eyes and mound of a belly were the excuse Amma used to get us to eat anything she cooked for us. But you always ask: Aren’t people poor in India? I guess. I don’t know. I’ve never been. We did get free tuition at the Catholic school, all three of us: Agatha Krishna, me, and Narayan. To be fair, almost everyone did. Marley is an oil town, and we were in a bust, bust, bust.

6. We weren’t Hindu; I know that’s what you assumed. There are a lot of Christians in India. St. Thomas was martyred there. By the time we killed my uncle, we had been parishioners of St. George’s Episcopal Church for years, nearly all twelve years of my life. Agatha Krishna had just been confirmed the year before. For a while, our priest, Father Stewart, had been unsure if Agatha Krishna was ready to give a “mature public affirmation of her faith.” His doubt stemmed from a worksheet she’d had to fill out on basic church vocabulary; when asked to explain what a bishop was, she answered: a chess piece that can move diagonally. But she was confirmed anyway. And because she, as an Episcopalian, had missed the pleasure of a first communion years ago when the rest of her class at school had received the Holy Sacrament, my mother allowed her to wear a white dress and veil for her confirmation. Most of the other kids wore starched Gunne Sax dresses and pressed khaki pants, but Agatha Krishna donned white from head to toe. She even wore a pair of white gloves I suspected she stole from the acolyte’s closet in the church basement. I had seen her take a handful of Dubble Bubble from the Mini-Mart, forgetting the eighth commandment. But she gave me a few and knew I would not say a word.

7. There is some of that in this story. As I said, we blamed the British, whom we had no real sense of, as we knew no actual British people. But we blamed them whenever something went wrong. We blamed them when it rained. We blamed them while we sipped milky tea instead of pop. We blamed them for Amma saying to-mah-toe. She, of course, liked the British, even if she never admitted it outright. She had gone to a British school, had followed the curriculum for the senior Cambridge exams in Madras, where she’d grown up. She could recite Shakespeare. She had once met Lady Baden-Powell, one of the founders of the Girl Guides, and her enthusiasm for Powell’s mission is the reason that Agatha Krishna and I both were Girl Scouts. And then there were our names. I was named after Georgette Heyer-Georgie Ayyar Creel, a clever play on my mother’s maiden name. Heyer was my mother’s second-favorite writer. Her first was Agatha Christie, who, of course, was Agatha Krishna’s namesake. She was always Agatha Krishna Akka to me, or AK Akka. Amma insisted I add the Akka. Though Agatha Krishna never called me Thangachi. Heyer and Christie wrote at more or less the same time. They were good wives and had both followed their husbands to places like the Caucasus Mountains and Tanganyika, Cairo and Baghdad. They both wrote mysteries, although Heyer was better known for her romances. My mother, as a schoolgirl in India, ate up Heyer’s Regency stories just as she did Christie’s tales of drawing rooms with Oriental rugs and cups of tea. Christie was later made a dame commander of the British Empire; Heyer never received any awards, but her husband was appointed Queen’s Counsel. All of which is to say—we were named after proper white ladies, even if we ourselves were never proper anything.

8. Yes, there are a lot of cattle in Wyoming. Yes, I eat meat. Again, when Appa was away on rigs, Amma would serve us tins of meat. And hot dogs that floated in boiling water. Hamburger patties cooked until there was no pink left in them. At school we ate meat with names of people: sloppy joes, Salisbury steaks, and shepherd’s pie. Amma did not consider chicken meat. Some nights she’d coat chicken in Shake ‘n Bake, then grind pepper into the crumbs. She’d turn and turn the grinder until the chicken was almost gray.

9. Magical realism and/or the uncanny. Being of color is uncanny. Why do we need any more? You will always be Your skin a mystery. Your presence unsettling. There—I think that’s it. Now I can tell you the rest of the story without worrying that I’ve forgotten any of those details I know you’re anticipating. Now I can be free to tell you the story I want to tell you, in exactly the way that I want to tell it. I’m not very good at this ventriloquist act. I am, after all, half-and-half. People tend to be fascinated by half-and-half beings. The fat Ganesha with his elephant head and pudgy man body. The jackalope with horns like a gate behind its ears. Mermaids, centaurs, satyrs, and sphinxes. All peculiar. Me, I take my skin—which is brown, not blue—and gather you round like Gopis.

Does it bother me that you want to hear the story this way? Yes. Does it make me angry that you need all of these specific details to feel like you’re reading a proper brown-person story? Yes.

But what did I ever do to you? you say. I’m not the one who made the world this way, you say.

And then you’re blaming the colonists too—but, of course, you’re nothing like them.

Aren’t I allowed to be angry though? Even just sometimes? Usually, I work hard to please, keep my head down. But now, let me be angry.

And if you’re lost, if you have no idea what I’m talking about … If you’re wondering what the big deal is … It’s brownness. It’s being the Other. It’s having to perform. It’s what happens when people are split, when countries are split. I have been performing forever. My own little dance. But I’m going to stop now. You can take it. I’ve been taking it my whole life.

__________________________________

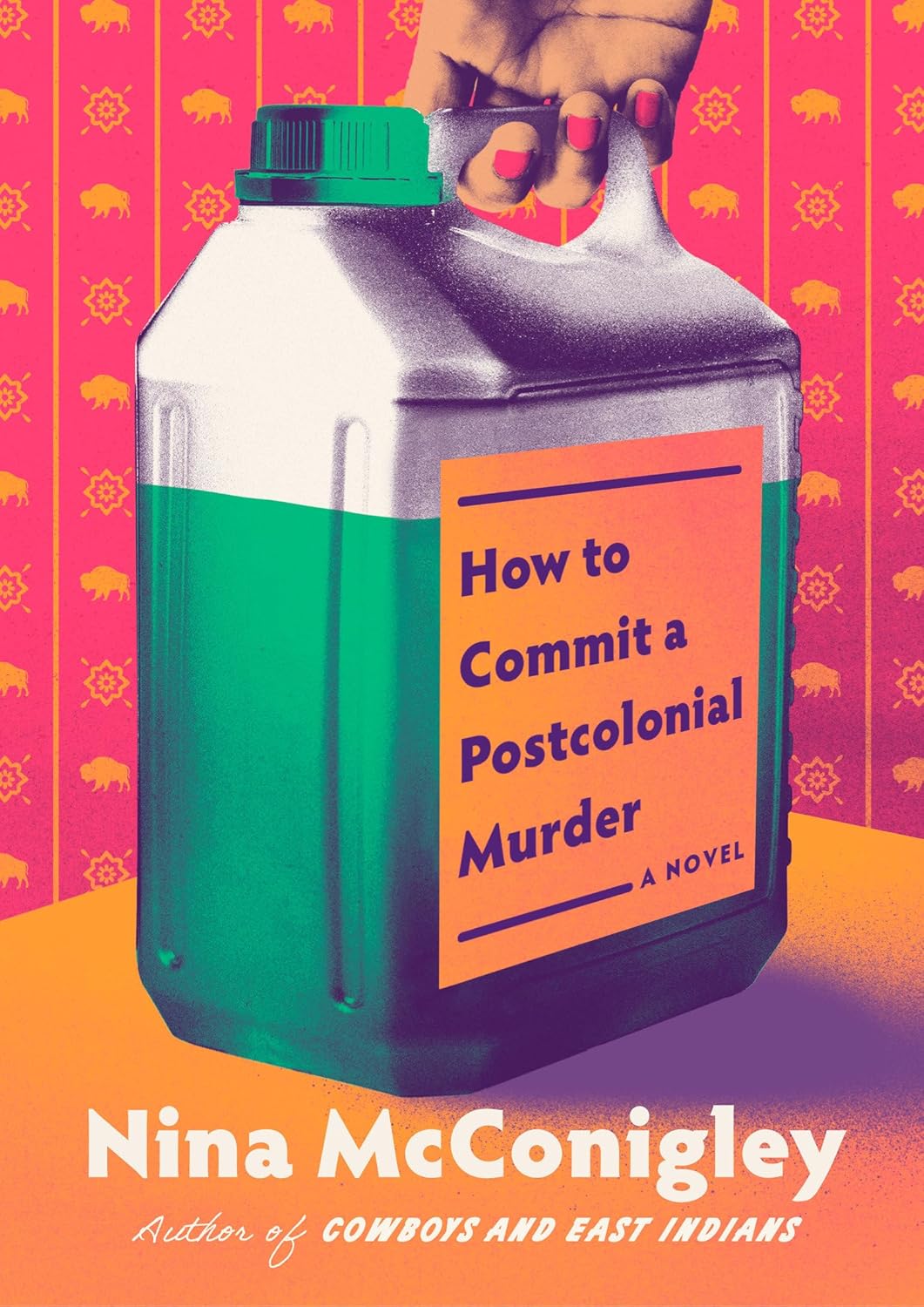

From How to Commit a Postcolonial Murder by Nina McConigley. Used with permission of the publisher, Pantheon. Copyright © 2026 by Nina McConigley.