Bluebeard, as he was called on the gossip sites, had two houses: a penthouse on Fifth Avenue facing the park and a blue beachfront mansion in East Hampton. And by blue, I mean painted bright blue, so that at certain times of day, in certain weather, it merged with the sky. He also had a blue Bugatti, a nineteen-foot TV with surround sound that could be controlled from anywhere in the world, and, for all of his computers, brass keyboards with round typewriter keys, which run about two grand apiece. His dyed beard was touted as one of his many eccentricities.

I’d grown up as a year-rounder in East Hampton. We lived in a modest, two-story house with cedar shake siding that had long been mottled gray. In summer, the Hamptons was the picture of the American Dream: polo-shirt-wearing families on sailboats, licking ice cream from waffle cones. I befriended kids who disappeared into boxwood hedges at the end of August, never to be heard from again. In winter, it was as if we lived at the ends of the earth.

Until Bluebeard bought the property across the street, our neighbors had been the ever-elderly Pearsons: two, then one, then grown children in to sell the place. The house’s best feature was its size—so small that we could see around it, out across the tan-green beach grass into the beautiful blue beyond. At dinner, in the years following my father’s sudden death from a pulmonary embolism, my mom would stare out at the water as we ate. “At least we have that view,” she’d say.

My sister, Naomi, two years my senior, used to paint that view scrunched up on a lawn chair in the Pearsons’ backyard. She painted on damaged canvases my mom brought home from the art store where she worked, thus the skies were cracked through with lightning or punctured with invented constellations.

Construction on the mansion had already begun when Naomi moved back to the home I’d never left. She’d earned a big scholarship and gone away to college, while I’d stayed home, saving money by commuting back and forth to Stony Brook. Naomi’s boss at the nonprofit where she’d worked had wept when he laid her off— wept. He had been forced by policy—last one in, first one out—he hated to see her go.

The mansion loomed higher, wider, bluer by the day. Our view disappeared first, then the morning sun. “Sticks out like a sore thumb,” my mom repeated each morning at the kitchen window, scowling as she brushed her teeth in the sink. Our house had only one bathroom.

Ashton Adams—that was Bluebeard’s real name—sent a neighborly gift in a bright blue cake box. Our last name was emblazoned in raised, gold script on the top of the box, which itself was tied up with a silky blue ribbon. A surprisingly thoughtful, analog gift for a twenty-eight-year-old tech billionaire. We’d all read the articles.

The cake box was so elegant, we were hesitant to touch it, though the smell was hard to resist. We gathered around it with forks. “A gift from the enemy,” said Naomi.

“He’s kind of famous,” I said, more as fact than excuse. I did the honors of untying the blue ribbon, letting it fall gracefully from the box, the way silky underwear might slip off a smooth leg. I traced the gold letters of my last name with my fingertip. I rarely saw my name in script. If anything, it was in Times New Roman and I’d typed it myself.

“Let us remember that he’s a tool,” said Naomi.

“What’s with the hideous blue thing on his face?” asked my mom. “Is it meant to distract from—the rest of his face?”

“It’s a hipstery thing,” I said. “It’s marketing,” said Naomi.

“People dress all kinds of ways,” I said.

“You don’t dress all kinds of ways,” said my mom.

This was true. It was a flaw. To work, I wore black pants paired with abstract-patterned blouses reminiscent of corporate wall art. Indeed, a shirt in my rotation matched a spongy, tan-brown painting across from the elevator bay at the dingy headquarters of the budget clothing company where I did menial labor for the marketing department. The job had little to do with my degree in English, my minor in creative writing.

“I heard he chews through women like bubble gum,” said my sister. She had somehow mastered a sophisticated Anthropologie-Patagonia look, though she shopped only at thrift stores. “Chews, chews, and spits them out,” she said. “Pays millions to make them scarce once he’s through.” She put down her fork. “Wouldn’t have to pay me.”

I opened the cake box, the massive side tabs pointing toward the ceiling. The cake was a brilliant robin’s-egg blue, yet the color barely registered in the face of the scent: sugar and butter, coconut and almond, a hint of vanilla, musky and warm. I imagined the vapors rising from the box, tickling my nose.

I didn’t bother with a plate. I slid the fork into the cake, the cake into my mouth. “I—” I began but put up a finger instead. I couldn’t speak. The smell was nothing compared to the taste. The flavors bloomed in my mouth. The texture was perfect—soft and light, the frosting rich and creamy.

My mom and sister stared.

“Are you having a religious experience?” asked Naomi. “What were you going to say?” asked my mom.

But I couldn’t for the life of me remember.

* * *

It was my sister who was invited to the party.

We’d witnessed several of Ashton’s parties from afar: the valets in the driveway whisking away convertibles, the energetic thump of live DJs, the splash and echo of night-swimmers in the pool and on the beach, the crackle of fireworks over the water. No one ever seemed to sleep, not even me, as I watched from my bedroom window, the sky bleeding blue with the afterglow of fireworks I couldn’t see.

Naomi ran into Ashton at the mailbox one day while he was out walking his four Tibetan mastiffs, whose blue-gray coats had been cut to look like lion manes. I had never seen him walk them himself. One of the dogs sniffed toward her, and he tight-fisted the leash, then yelled, “STOP,” with such a commanding voice that all four dogs froze like statues.

I watched from the window through a gauzy curtain, hands on the back of the faded floral couch.

When she returned, I accosted her in the doorway. “What happened? What did he say?”

“If you want to know anything about Tibetan mastiffs, I’m pretty sure I just got a rundown of the entire Wikipedia page. I doubt I could do justice to the pretentious tone.” She slipped off her silver mules, leaving them next to my gray sneakers, and walked into the kitchen to start dinner.

“He’s just smart,” I said, following her. I’d heard him speak on a podcast once. “He’s articulate.”

“You mean he articulates every. Single. Word.”

“Not everybody’s smart and socially adept like you,” I said.

“Do you know why he’s rich?” she said. “He steals data from the masses. That’s his job.” She took out the curry powder and cumin and mustard seed. It was a real step up from my specialty: meals poured into pans from frozen bags. “He’s pushing his personal brand,” she said. “Condescension wrapped in blue. Guess you can sell anything if you know how to package it.” She threw me a bag of tiny black lentils to rinse. “We need a cup of those,” she said. “I’m not going to any party.”

“Wait, what!?” I squealed. “He invited you to a party?”

“Come on, Berry,” she said as she diced an onion with incredible speed. “It’s just curated speed dating for him. He called it a ‘shindig.’ ”

“Who cares what he called it!”

“No thanks,” said Naomi. Of course. Like someone beautiful explaining why beauty doesn’t matter, or someone rich explaining that money doesn’t buy happiness.

“I want to go,” I said. “Let’s go. Do it. For me.”

She looked up from chopping, her eyes red from the onion, though I imagined it was pity for me.

“Please,” I said.

“Fine,” she said. “For you.”

A blue-tuxedoed doorman took our phones at the door, giving us each a four-digit number to memorize in order to get them back at the end of the night. Then he welcomed us into The Great Room with an open arm and a bow.

The back wall was made of windows overlooking the beach view that had once been ours. Partygoers orbited the room, women in cocktail dresses, in bikinis, in wide-legged jumpsuits, men in slacks or ties, a few bow-tie-and-glasses types, and a crowd of lanky, unshaven men in blazers and tees emblazoned with Ashton’s company logo. Each person held a different-shaped glass, crafted to match the owner’s chosen drink. The drinks were retrieved outside, under a thatched-roof bar between a pool and a life-size chessboard where two men were dueling with bright blue pawns.

I wore an eggplant-colored cocktail dress, a former bridesmaid ensemble replicated down to the costume jewelry. It was my most flattering dress, obscuring my stomach while still showing off my behind, my best physical feature. Naomi wore a cream-colored sundress embroidered with flowers, her hair in a halo of braids.

I’d seen my share of seafood buffets at the weddings and showers of monied friends, but I’d never encountered such a grand display. It was as if a tsunami had deposited an ocean’s worth of inhabitants right there in The Great Room.

Blood-red lobster claws dangled over blue crabs with red-tipped pincers like painted fingernails; disembodied crab legs splayed out from ice buckets beside trays of pale oysters; pink-white shrimp and prawns stared out with wet black eyes, their bodies boiled into curls, spidery antennae and legs all pointing in the same direction. The accouterments of extraction were laid out on a white tablecloth beside like antique surgical equipment: long, thin seafood forks, pent-up and dainty; menacing curved shears; crackers with heavy, opulent handles. When my sister went to the bathroom, I didn’t know how to act. I had yet to see Ashton. I wandered away from the seafood table to a big, beaded couch in a corner near the window. The tiny beads were all shades of blue—ultramarine, royal, aqua—but what struck me most was the wave of midnight beads, so dark they matched the ocean waves shimmering under a bloated moon.

A woman outside removed all of her clothes dispassionately, as if she were undressing in her bedroom. Her silhouette looked familiar. She had a long, elegant nose that turned up, just slightly, at the tip, and shoulders that curved in as if she were hiding or protecting something inside her. Had she been out in the neighborhood once, walking his dogs? For a second, she seemed fleshless in the moonlight, then she executed a perfect dive into the infinity pool that looked as if it fell directly into the sea.

A hand on the small of my back, and I jumped. It was Ashton, the bright cyan blue of his perfectly trimmed beard so vibrant that it obscured every other physical fact about him.

_________________________________

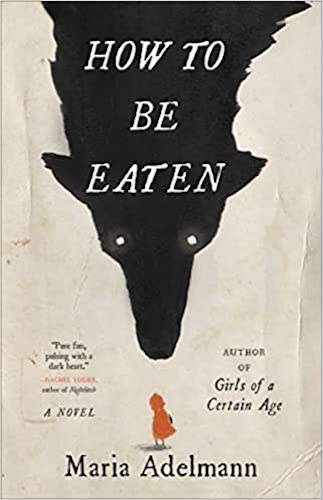

Excerpted from How to Be Eaten by Maria Adelmann. Published by Little Brown. Copyright © 2022 by Maria Adelmann. All rights reserved.