How to Be Cool: On the Societal Expectations Placed on Black Boys vs. White Boys

Brian Broome Considers the One-Two Punch of Gender and Racial Identity

Whatever it was, I already knew by ten years old that I didn’t have it.

I couldn’t access it. Couldn’t summon it. Couldn’t fake it. But the boys all around me had it in spades, this elusive quality that only Black boys could possess. White boys didn’t have it. Whenever they tried to pretend that they did, it came off forced, stiff, and rehearsed. When they tried to be “cool,” you could see right through them. I didn’t possess this quality either and I knew of no way to make it come to me.

It’s a trait that defies verbiage and the only thing I could understand about it at the time was that it seemed to involve an almost superhuman ability to lean on things. Up against buildings and telephone poles and cars, not giving a shit about the thing upon which you are leaning. Nor should you appear worried about that thing shifting under your weight to send you crashing to the ground. It seemed to hinge on the absolute belief that whatever you were casually leaning up against would support you, because you, after all, are you.

I learned what white boys do, and what Black boys are supposed to do to counter it at the foot of the master: my best friend, Corey. When we were ten years old, we sat in his bedroom after school surrounded by his baseball, basketball, and football equipment as he admonished me. The differences between Black boys and white boys, he explained, are vast and it is entirely up to the Black boy to make those differences clear. White boys could just do whatever. But Black boys had to show through our behavior that we were undeniably, incontrovertibly the most male. The toughest.

We sat on either end of his bed and I got lost in his pretty brown eyes as he explained that white boys were basically girls—“pussies”—and that there was nothing worse than a boy being like a girl. I stared blankly, wanting to kiss him. According to him, the seemingly simple act of being white and male made one “soft” and a “punk,” but Black boys were constructed of special stuff that made us stronger, colder, cooler. All I wanted to do was hold his hand. But I listened because he was beautiful. He was light-skinned with curly black hair and straight, white teeth. He was the polar opposite of me, too dark-skinned with the teeth in my head crawling all over each other like they were trying to escape a house on fire. He talked on as I got lost in his face.

“White folks,” he explained, “won’t let you do anything anyways, so you gotta show ’em. All they do is fuck wit Black folks all the time, so you gotta prove to ’em that you won’t be fucked with right from the start. That’s why white dudes be scared of us, because they know that, when it get right down to it, we cooler. That’s why they women always come for our dick.”

I didn’t understand any of this. Corey explained that the rules were simple. There were girl things and there were boy things and white boys liked girl things and acting like a white boy or a girl of any color was prohibited. The list of “girl things” included: studying, listening, being “pussy-whipped,” and curiosity. There were categories and subcategories, but being pussy-whipped was the worst of these transgressions. Corey explained that Black boys were to always be in control of girls.

There were no gray areas and, each time I visited his home, he scolded me about how he’d heard I’d messed up that day at school. He never interacted with me in public. He called me “white boy” and doled out punishments for my behavior that were severe. He “play punched” me to toughen me up—blows to the side of my head or in the arm that were so hard that I knew somewhere deep down inside that he really didn’t like me at all.

Our “play wrestling” moved from play to real rapidly, like a switch had been flipped inside him. He bloodied my nose many times. He split my lips against my crooked teeth and once locked me in a port-o-potty by eliciting the help of other boys to lean on the door from the outside. The injuries that I sustained from him were dismissed by the adults as a result of “wrastling” or playing like horses. He wasn’t whupping my ass, really. He was pummeling the girl out of me. I took his disguised ass-whuppin’s almost every day, believing that, one day, he would deliver the one punch that might change me.

I didn’t know where Corey’s father was. It never came up and something told me not to ask. He lived with his mother and there were times when I wanted to tell on him. But she treated him as a crowned prince who could do no wrong and, the one time I tried, I was only asked accusingly “Well, what did you do to him?” and then admonished for being a “tattletale,” which as near as I could tell was a girly attribute.

The house was his. He had full dominion. He had all the new toys and his own stereo. His clothes seemed to be perpetually new. The denim of his blue jeans was always that rich, deep shade of royal blue, rolled up at the cuff to reveal the lighter shade of blue underneath. Unlike me in my old and dingy clothes, Corey was always fresh and his clothes fit him perfectly. He treated his mother like a servant and talked to her in a brazen and dictatorial way. He once told her to shut up, and I was left awestruck as I waited in vain for her to go upside his head like my mother would have with me. But all she did was shut up. I had never seen a Black boy with such power. He was a force in his house. He had the biggest say-so. I wanted to be him.

Black boys had to show through our behavior that we were undeniably, incontrovertibly the most male.

When I arrived at his house on a Saturday, I let myself in and stomped the snow from my boots. That winter was especially brutal. I was sent to his house by my parents every weekend and I mostly dreaded it. Whole days with him were a merciless trial. He was unpredictable. Moody. He called me poor and ugly. I never felt good when I left his house, nursing a Corey-inflicted wound that I chose to hide from my parents later. But my father was concerned about how many girls I was playing with on a regular basis.

I was sent to Corey as a form of therapy. My father loved him and would clap him hard on the back whenever he came around, and they would laugh. I wanted that from my father too and believed that Corey could fix me. I didn’t mind that much if every once in a while, that fixing resulted in a fat lip. I knew that he was the epitome of cool. Everyone did. I was grateful that he was my friend, and, for some reason, I felt he needed me as much as I needed him.

After I stomped the snow from my boots, I removed my jacket, scarf, and hat and hung them on the coatrack by the front door. I walked down the hallway past the living room, where his mother was in her seemingly perpetual position in a lounge chair mindlessly doing crochet and staring at the television.

“Hi, Brian.”

His mother said this vacantly and with no enthusiasm, not so much reacting to my arrival as she was to the sound of the door opening and closing. I walked to Corey’s closed bedroom door and hesitated, listening to him doing some sort of karate on himself on the other side. I took a deep breath and knocked lightly twice. The door flew open.

He didn’t even give me time to step inside before he grabbed my elbow, pushing me backward toward the very rack upon which I had just hung my hat and coat. He was fully dressed to go out into the snow. I didn’t want to go back out, but there was no time for argument. He was in a rush. Seized by some sort of urgency. He explained to his mother quickly that we were going outside to play. He hissed “Hurry up!” at me from between clenched teeth and his mother looked up absently from her crochet to the window at the blinding snow coming down in drifts and then back at us with incredulity. I wanted her to tell him that we couldn’t go, but then her face went blank and she returned to the mess of yarn on her lap. When I was fully dressed again, Corey all but shoved me out the front door, and it was only when we were a safe distance from his house that he began to explain.

“Everybody callin’ you white.”

“What? Who?”

We were walking through the field behind his mother’s house and the snow was coming down so heavily that my face was already wet. Our footsteps were synchronized so that the deep snow under our feet crunched at the exact same time in a rhythm that made me feel as though he and I were actually friends. We headed toward the woods. The sky was the color of concrete and the branches of the trees were stripped naked of their leaves and heavy with snow. When we were deep into the woods and surrounded by them on all sides, Corey spoke again.

“Everybody. They say you act like a white boy and a fag and I told them you don’t. I stood up for you. But they don’t believe me, so we goin’ to meet a girl.”

“What girl?”

“Some girl. You gon’ fuck her.”

I didn’t mind that much if every once in a while, that fixing resulted in a fat lip.

Corey explained that a council of Black boys in the neighborhood had met up and the topic had turned to why I was coming to his house on weekends. They knew, and he didn’t like that. Corey’s honor was at stake. He now had skin in the game. They had discussed such subtopics as how I was basically a white boy and a punk, and how I had failed to display the proper balance of nonchalance and boisterousness appropriate for a boy. They discussed my cursed bookishness; my disinterest and ineptitude at sports; my inability to lean against buildings, telephone poles, and cars; and the fact that I played with girls. In short, I was just not cool. It had been suggested that, by having kept company with me, Corey was a faggot by association. This could not stand. And now I was being taken to go fuck “some girl” to prove that Corey had not been hanging out with a sissy. I was to prove that I was not an insult to my race and my gender.

We marched through the snow until we arrived at the abandoned barn behind a neighbor’s house. It was more of a garage, really, but had the look of an old barn that had fallen into disrepair. The pit of my belly was alive with fear and confusion.

__________________________________

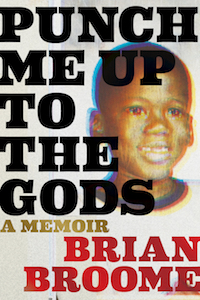

Excerpted from Punch Me Up to the Gods: A Memoir. Published and reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2021 by Brian Broome.

Brian Broome

Brian Broome, a poet and screenwriter, is K. Leroy Irvis Fellow and instructor in the Writing Program at the University of Pittsburgh, where he is pursuing an MFA. He has been a finalist in The Moth storytelling competition and won the grand prize in Carnegie Mellon University's Martin Luther King Writing Awards. He also won a VANN Award from the Pittsburgh Black Media Federation for journalism in 2019. He lives in Pittsburgh.