How to Be a Beatles Fan Without Really Trying

Sibbie O'Sullivan on Privacy and Fandom

I can easily picture my English friend Sarah at age ten alone in her London bedroom worrying about how she’d take care of Mr. Rochester now that he’d gone blind and then a second later contemplating ways she’d murder Cynthia Lennon—poison? lacrosse stick? It’s good to have imaginative, precocious friends.

I was 35 before I read Jane Eyre. At ten I was reading The Adventures of Robin Hood and His Merry Men and following Prince Valiant in the comics, so I did my part for the empire. But Sarah? Sarah was hardcore. Still ten, while attending Broomfield House elementary school, Sarah became president of the school’s Beatles fan club, what she considered an act of public service.

Fan clubs were instrumental to Beatlemania. The first official one was in Liverpool and run by Freda Kelly, who became a loyal and long-term employee of the band. The ones that followed comprised a scattering of schoolrooms, bedrooms, and other teenage hangouts. At Broomfield House, Sarah lined up the letters, posters, and postage stamps, gathered the photographs and other Beatles ephemera. She was in charge. She had a patriotic duty to fulfill. Fifty-two years later, her Delft blue eyes still blazing with indignation, she tells me, They were ours before you took them from us.

Sarah has a point. The Beatles conquered her country in 1963, and then in 1964 they conquered mine. Soon they had conquered the entire world. But only England had Swingin’ London, and a few years after Broomfield House, my pal Sarah, now a mini-skirted student at St. Paul’s School for Girls, partook of a London scene American girls could only dream of.

South of London, some miles from Sarah, my friend Ian watched the Beatles for the first time on television and remembers thinking how authentic they were. To Ian, the Beatles were talented working-class guys who didn’t defer to authority or status; they were real, and they were funny. Those two traits resonated. When I told Ian that John’s favorite books were the Just William series, he let out a little yelp and said, My God, you’re taking me back to my childhood. Stop it. Books adhere across classes, and so does music.

Bob, another English friend, grew up in Brighton and wasn’t permitted to listen to rock and roll in his house, but he remembers his older sister taking him to Elvis movies. Bob became a musician and recording engineer and once saw John Lennon in the hallway of Abbey Road studios. I wish he hadn’t told me this over lunch. It’s not polite to gape when you’re chewing a turkey sandwich.

By virtue of gender, teenage boys could hope to become the Beatles, whereas Sarah and other girls could fantasize only a proximal identification by becoming a Beatle’s wife.

Bob moved to the States in the 1970s. The night of December 8th, 1980, around 10:45 p.m. he was driving home while listening to a local DC radio station that played requests. That night the requests were for Lennon songs. In the middle of the playlist, the DJ broke in to say that someone just called the station claiming John had been shot. Was this a sick joke? No; a few minutes later the deejay broke in again and made an official announcement: John was dead.

In America, there’s no place more private than the front seat of your car late at night.

You’re alone, you’ve got a good station on the radio, it’s dark inside and out, and you can have as many Travis Bickle rants as you like, because no one will ever hear them.

I didn’t ask Bob what he was thinking as he drove home that night, but I can imagine. Only in America, gun-happy, full-of-weirdos America. Or maybe he thought how strange the layering was of that specific moment on the radio, one so serendipitous he might be tempted to disbelieve in serendipity altogether considering the unlikelihood of hearing Lennon sing and then learning that he’ll never sing again. It’s enough to make you laugh, something Lennon might have done were he in the car, given how acquainted he was with unexpected death.

Or cry.

Private moments, even for a girl of ten, permit her to claim something of the Beatles for herself that’s different from the wider spectacle unleashed by screaming fans. Sarah remembers being secretly happy that her favorite Beatle, John, was “the intelligent one,” and in the privacy of her room she drew a parallel between him and the charismatic Mr. Rochester beyond what we might expect of a ten-year-old. Daydreaming encourages such alignments.

Bob, like many other young men, made a private aspiration public by forming a band. By virtue of gender, teenage boys could hope to become the Beatles, whereas Sarah and other girls could fantasize only a proximal identification by becoming a Beatle’s wife. Regardless of the outcome, privacy of thought and feeling is a guard against all “official” response to experience.

After the band broke up, the Beatles industry took off; John’s murder predictably intensified this acceleration. More books, more photographs, more exposés, all of which potentially swayed fans to forget one’s private experience of the band and identify with whatever published history most suited them. But the opposite was also true.

The contested truths about the band, especially who wrote what, along with the intricacies of the recording sessions, elevated Beatles criticism to a new level, and for a certain type of fan, the close textual analysis of Beatles songs, including discussions of psychological differences that could explain artistic differences (e.g., John is “horizontal,” Paul is “vertical”), enhanced their private feelings about the band.

“There’s a Place” is an early Beatles song that asserts the value of privacy. The “place” is John’s mind, where “there’s no time / when I’m alone.” Sung with great insistence and piercing harmony, for many male critics this song is loaded with significance beyond the usual romantic concerns its lyrics imply, for instance, being blue.

For Ian MacDonald, the song represents “a young man’s . . . assertion of self-sufficient defiance.” Steve Turner hears the lyrics as a search for “comfort,” while Tim Riley insists on the song’s “innocence.” For Geoffrey O’Brien, the song is a “stand in for the overall value of the Beatles . . . [a] sonic environment [that] turned out to be an excellent cure for too much thinking.” Robert Christgau hears John’s “ability to transcend the isolation he dreads.”

Initially, I didn’t know what to make of such serious regard for this song. You certainly can’t dance to it, and it’s quite short. It’s one of those quirky Beatles songs that defies category. John dismissed it outright, yet it’s impossible to separate John from the song’s impact because it’s his mind we’re going into.

The song’s title also invites us into a literal place, John’s small, front-facing bedroom in Aunt Mimi’s house. That room is the place of his earliest writings, his private thoughts, but also the place he frequently escaped from—to visit his mother, or to try his luck in Hamburg, and later to lay musical claim to the Cavern Club and a sexual claim to its female patrons. In 1960, after the group was kicked out of Hamburg, John, alone, penniless and dejected, returned to this narrow room. It was a young man’s room.

__________________________________

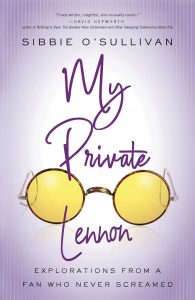

Excerpt from Sibbie O’Sullivan’s My Private Lennon: Explorations from a Fan Who Never Screamed, used by permission of Mad Creek Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press

Sibbie O'Sullivan

Sibbie O’Sullivan is retired Senior Lecturer in the Honors College at the University of Maryland. She is a book reviewer for the Washington Post, specializing in music, culture, and the arts.