How the Word “Landscape” Helped Change Americans' Relationship to Nature

Tyler Green on the Emerson-Inspired Language Shift and Its Meaning for Wilderness and Civilization

In September 1836, 33-year-old Ralph Waldo Emerson, then a local figure known principally for resigning a plum pulpit at Boston’s Second Church, anonymously self-published a 95-page book called Nature. From a humble beginning and slow initial sales came the most-read and most-influential essay of the American 19th century, an essay that within its first 80 years would be published in around 190 English-language volumes—and printed in who knows how many editions. After I detail some of the ways in which Emerson’s engagement with art informed and helped instigate Nature, this volume offers it anew—along with some critical suggestions about how Nature may have, in turn, informed American art.

Nature is not just a celebration of flora, it is among the most important 19th-century proposals for the basis of an American national culture. It argues that the Union should root its literature, poetry, faith, and art in that which is uniquely and specifically American instead of in the traditions, religions, and institutions of monarchical and aristocratic Europe. “There are new lands, new men, new thoughts,” Emerson wrote in the book’s first paragraph. “Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.”

Emerson specifically offered America’s nature—not just its trees, lakes, and rivers, but the Union’s republican nature—as reciprocal expressions of our culture. While the outdoors was at the heart of Emerson’s idea—lest anyone miss it, his book’s first cover was imprinted with a pattern born from leaves—Emerson repeatedly juxtaposed the beauty of the natural world from which the country’s faith and art and literature should be built, with human nature, suggesting that these natures would be reflected in the greatness of the country of which they were parts.

For Emerson, that nature is a word with multiple meanings was part of its attraction. Nature’s text is constructed around a series of reflections, both thoughts, as in a man’s ability to reflect on the beauty of an oak, and reflections manifested as halves mirrored into wholes. In a related story, in a republican state, government reflects the will of the electorate. Nature is 16,000 words of winking wordplay. (And about those leaves on the cover: a book is itself bound leaves, a witty nod to Nature’s material construction.)

Emerson further suggested that American culture be constructed from individual Americans’ direct experience of the natural world. Again, Emerson offered a contrast with Europe, where people were subject to both royals and landed aristocrats, and where churches and their clergy mandated forms of worship and dictated to their congregations how the Bible would be understood. In republican America, Emerson emphasized, people think for themselves, and American institutions, such as government, were designed to respond to the individual (or as we recognize it today, to the white male individual), to reflect the electorate.

Emerson offers a unit within which nature might be considered, a frame: landscape.

In pointing Americans to their own direct experience of nature, to make and trust their own personal observations rather than relying on monarch-down political models or ossified European religious dogma, Emerson urged Americans to broaden and fulfill their republicanism, to make it cultural as well as political.

But how to explain how this might be done? After all, nature is something of an abstraction, and the exhortation to nature is so broad as to be almost meaningless. Understanding this, Emerson devoted the third paragraph of his very first chapter to offering a unit within which nature might be considered, a frame: landscape. Emerson, who always defined the terms he used when he wanted to ensure both maximum clarity and maximum impact, defined landscape thus:

The charming landscape which I saw this morning, is indubitably made up of some 20 or 30 farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet. This is the best part of these men’s farms, yet to this their land-deeds give no title.

Note especially that Emerson chooses landscape and not wilderness, then the more common point of American cultural address. In case readers missed it, at the end of the next paragraph (and just after the famed “transparent eye-ball” passage), Emerson pointedly contrasts wilderness and landscape. In untamed wilderness, Emerson says, he finds “something more dear and connate than in streets or villages.” In “tranquil landscape . . . man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature.” Emerson was insisting upon a distinction, and with it he was trying to pivot from a European construct and America’s own past to America’s present and future.

Historians, especially art historians, have paid little attention to Emerson’s definition of landscape or to his advance past wilderness. Instead, they have constructed their examination of the range of American experiences of the great outdoors around contemporary definitions, especially of landscape, rather than 19th-century usage and definition. To fully understand Nature and its impacts, including the ways in which artists likely engaged with Emerson’s ideas, it’s important to remember what landscape meant (or was beginning to mean) in 1836.

Noah Webster’s 1828 first “American dictionary of the English language” defined wilderness as “a tract of land or region uncultivated and uninhabited by human beings.” (Key to Webster’s definition was that Native Americans didn’t count as human beings. We will return to this.) The address of perceived wilderness was crucial to colonial America’s westward growth in the 17th and 18th centuries and then to the emergence of the American independence movement in the 1770s.

As European colonists, and later Americans, moved inland from the Atlantic coast, up river valleys, and then westward, they converted perceived wilderness, forests, and grasslands, much of it land inhabited by Native Americans, into lumber, farms, and mines. Culturally, too: both French Catholic Canadians and New England Protestants considered the American project as pitting God’s paradisal garden and civilization against the dangers within Satan’s wild wastelands. Wilderness was the subject of one of the first great American novels, The Pioneers, or the Sources of the Susquehanna, James Fenimore Cooper’s wincing 1823 narrative of how westering Americans recklessly consumed land and natural resources, and of how they treated indigenous people as a momentary obstacle to white progress.

Landscape was a new word, and as Emerson wanted his audience to move on from wild wilderness to man-impacted American nature, using a new word was itself a prompt.

In The Pioneers, Cooper references “wilderness” 29 times (and uses “landscape” just twice, including once in a usage that American English soon forgot.) Wilderness was also an important subject for artists, and especially for the first great American painter, Thomas Cole. Furthermore, as a point of cultural address, wilderness had its origins in Europe, such as in the place to which St. Jerome retreated to translate the Bible into Latin.

It was within these then contemporary contexts that Emerson offered landscape, not wilderness, as the place where Americans might embrace nature. With landscape, Emerson was turning away from the European church’s binary, civilization-versus-wilds view of nature and toward an idea that made room for an interstitial space between urbanity and wilderness, and thus for American agrarian republicanism. Emerson understood that in the generations since Cooper’s fictional pioneers had begun to eliminate the trans-Hudson wilds, actual Americans had continued westward. They had pushed over the Appalachians, across the Ohio River, and into the Great Lakes region in the north, and through the Cumberland Gap and into Kentucky and Tennessee in the south.

Emerson knew that colonists and then Americans had already cut down and plowed thousands of square miles of perceived wilderness, so he offered landscape as the construct Americans might use to consider and appreciate these places they had transformed. Emerson uses “landscape” eleven times in Nature, each time in reference to a place that was man-impacted and thus explicitly not wilderness, including viewsheds, a view within town, a view on the edge of town, a view just outside town, and also to paintings.

Landscape was a new word, and as Emerson wanted his audience to move on from wild wilderness to man-impacted American nature, using a new word was itself a prompt. In the 1830s, landscape was recent to the English language, and more recent still to American English. Landscape is the English adaptation of landschap, a 16th-century Dutch word. Landschap referred specifically to paintings of the outdoors, a genre first made popular by Dutch and Flemish painters.

Landschap crept into English in the Dutch spelling before being anglicized into landscape in around 1725 (in an English translation of Homer). The English landscape began to divorce itself from colored-mud-on-canvas at the end of the 18th century as John Constable and J.M.W. Turner rose to prominence, and when Samuel Taylor Coleridge walked to the top of a forested hill outside Bristol, England, and exclaimed, “What a luxury of landscape meets My gaze!” Emerson, who helped extend America’s interest in Coleridge, understood that the word’s meaning was unsettled. He must have loved that his unit for the appreciation of nature(s) was a word in flux, that it meant both somewhere in the natural world and something manmade (a painting, but also a post-wilderness inhabited space), and that like nature (and like leaves and reflection), landscape was a homograph.

Nature would play a key role in nudging landscape from its Old World meaning as second-hand exploration, to its new American meaning as a human-impacted place encountered through a direct experience. The American landscape tradition in art and in other disciplines begins with Emerson’s definition and urging to landscape.

_______________________________________

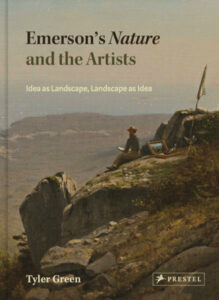

Excerpt from Tyler Green, Emerson’s Nature and the Artists: Idea as Landscape, Landscape as Idea (Prestel Publishing, September 2021).

Tyler Green

Tyler Green is an historian, critic and author whose work examines the ways in which artists and their work have engaged and often impacted national histories.