How the TV Adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots Sparked a Cultural Awakening

Wil Haygood on the History of Black Life on Screen

A good many Blacks of Ithaca, New York, in the 1920s worked as domestic servants in the fraternity houses near Cornell University. When those Black citizens sought news about other Blacks, they often turned to The Monitor, a local Black newspaper. Inside its pages were mentions of weddings and births and social goings-on throughout the Black community. Simon Haley and Bertha Palmer, two Ithaca Blacks, stood out in the community. He was in graduate school at Cornell, studying agriculture; she was studying music at the Ithaca Conservatory of Music. They met, fell in love, and married. In 1929, Simon Haley began teaching agriculture, moving from Black college to Black college in the South. The Haleys had three sons, Alex, Julius, and George. Growing up, the boys would spend their summer vacations with grandparents in Henning, Tennessee, 50 miles from Memphis, with a population of fewer than 600 citizens.

The Haley boys greatly enjoyed the rural landscape, where they could roam and fish. Their maternal grandmother, Cynthia Palmer, who had been born a slave, captivated them with stories of her history: stories about men who owned other men, who owned whole families; stories about escape attempts from slave plantations. They listened to sweet stories that told of weddings, slave weddings, in which a man and a woman would jump over a broom, an act cementing their union. They listened to stories about President Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, and how that law meant freedom and jubilation. The boys’ teachers never talked of such stories, of the most painful part of American history. A large part of their history had been denied them—until now. “Grandparents,” Alex Haley would come to say, “will tell their grandchildren things they won’t tell their own children.”

Alex Haley, a precocious sort, graduated from high school at the age of 15 and enrolled at Alcorn State University in 1936. After a year, he transferred to Elizabeth City State Teachers College in North Carolina. But college life proved difficult, and Haley left the school after two years. For a while, he seemed aimless and adrift. His father worried about him, and finally suggested Alex join the United States Coast Guard. The elder Haley knew that young men had long gone to sea in order to find themselves. The Coast Guard had been—albeit sparingly—allowing Blacks to join since before the Civil War. Those Blacks worked on ships as mates, the lowest of the menial duties. In 1939, Alex signed up for a three-year hitch. His job options hadn’t changed all that much from what was offered Black enlistees during the Civil War era. His rank after joining was “mess attendant third class.” Haley was assigned duty aboard the Mendota, a 250-foot cutter based out of Norfolk, Virginia. Coast Guard recruits mostly learned aboard ship, mentored by veterans.

Coast guardsmen, so often out on the water, did not have constant access to phone lines, so they tended to write a lot of letters. The guardsmen aboard the Mendota came to realize that Mess Attendant Third Class Alex Haley had a gift with language; he knew how to turn a phrase. This at first made his shipmates chuckle, then it made them envious, and with their envy they began pleading with him to dictate letters for them. Haley became a willing, smiling ghost writer. Just as he had done at his grandmother’s knee back in Tennessee, he was also listening to some of the older guardsmen tell stories about hurricanes and squalls and death-defying voyages.

He put some of their stories down on paper. There was a magazine, Coast Guard Magazine, and it was suggested to Haley that he might submit some of those stories. The idea excited him, so he started shaping his notes into narratives. Haley was told he had talent. He was transferred to another cutter, the Pamlico, based in North Carolina, in early 1940. Haley was there when World War II started. By May 1943, he was aboard the USS Murzim in the Pacific Theater. The idea of writing for publication was truly taking hold now. He wrote an article, “In the Pacific,” that was published in the February 1944 issue of Coast Guard Magazine. He wasn’t Hemingway, but it was war, and he was writing, and his stuff was getting published and drawing compliments from officers.

Haley came up with an idea to start a newspaper aboard ship, called Seafarer. He wrote an editorial about how sad it was that many of the men never received letters—from anyone. This editorial tugged at the emotions. Newspapers on land picked it up and reprinted it. Soon enough, letters started pouring in to the crew—from cousins, sisters, ex-girlfriends, even strangers. It all had a touch of Frank Capra, the sentimental filmmaker. Haley had burnished his bona fides as a writer. After the war, in 1949, Haley was promoted to journalist, first class. Then he was named “chief journalist of the Coast Guard,” the first such classification. He was transferred to land, to a New York City Coast Guard office. From a syndicated article that appeared in various newspapers at the time:

You can call him “chief ” now—the amiable, industrious and ever helpful Alex Haley, the man behind the public information phone at New York City’s Coast Guard Headquarters… When there’s a ship in distress along the Atlantic coast, a plane down at sea, a fishing party marooned or on any one of a hundred other mishaps, Haley’s the guy who feed[s] the newspapers and wire services the latest information.

The Negro press had a swell time writing about Chief Journalist Alex Haley. Haley finally left the Coast Guard in 1959, having put in 20 years. There was a pension, so he had a cushion, enabling him to write full-time. He had an overwhelming drive to retell some of the stories his grandmother had told him—stories about Africa and slaves and those ships landing in America.

Settled in New York City, Haley began getting freelance assignments. The editors at Reader’s Digest liked his work. The country was becoming more aware of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. Muhammad used his reputation to vouch for a lot of prisoners, guaranteeing to parole boards that they’d have job opportunities when released. One such prisoner was Malcolm X—stoic, sharp of wit and mind—who began rising in the Muslim Brotherhood. Haley got an assignment to write about the Muslims. His piece, “Mr. Muhammad Speaks,” appeared in the March 1960 issue of Reader’s Digest and drew both interest and praise. Haley later wrote a longer piece “Black Merchants of Hate”—co-authored with Alfred Balk—for the January 26, 1963, issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Muslims had begun playing a more prominent role in the struggle for Blacks to gain equal rights. Theirs was not a turn-the-other-cheek philosophy; it was self-segregation, and a vow to meet police brutality with confrontation.

Haley got an interesting assignment to interview the jazz trumpeter Miles Davis for Playboy magazine. The editors there liked the piece so much they began the “Playboy Interview,” a monthly feature. Haley became the go-to interviewer, and he went on to interview such figures as Sammy Davis, Jr.; Quincy Jones; Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell; and Malcolm X. The nude pictures aside, a lot of enlightened folk read the “Playboy Interviews.” The Malcolm X interview was such an eye-opening piece for both Black and white America that the two men soon embarked on a collaboration for Malcolm’s autobiography. They spent hours and hours together, Malcolm speaking into a cassette recorder, Haley asking hundreds of questions.

He had an overwhelming drive to retell some of the stories his grandmother had told him—stories about Africa and slaves and those ships landing in America.

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was delivering a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. Shots rang out. His assassination—three Muslims were arrested—further deepened the pangs of Black America. Doubleday was supposed to publish the Malcolm X autobiography, but canceled it after his death. The book was picked up by Grove Press and published in 1965, with both Malcolm X and Haley appearing as authors. The reviews were powerful: Truman Nelson, critic for The Nation, praised it for “its dead-level honesty, its passion, its exalted purpose, even its manifold unsolved ambiguities will make it stand as a monument to the most painful of truths.” Writing in The New York Times, Eliot Fremont-Smith proclaimed it a “brilliant, painful, important book. As a document for our time, its insights may be crucial; its relevance cannot be doubted.” In death, Malcolm X rose as a multidimensional figure. And Alex Haley had established himself as an important literary figure.

There was enough money coming in for Haley to focus on the family chronicle he was working on. To construct any family history is an arduous task, but it was especially so for Blacks, because official documents about their past were not often kept by towns or cities. And—depending on plantation record keepers—Blacks were often not accounted for in census records. Haley found clues in libraries in Southern archives, and in Britain. In Gambia, West Africa, he heard the name Kunta Kinte, whom he identified as one of his main ancestors. He located records of slave auctions. His notes and folders stacked up—four years turned into eight, eight turned into 12.

His publisher, Doubleday, finally published Haley’s book, Roots: The Saga of an American Family, in the fall of 1976. The praise it received seemed endless. Many other books about slavery had been written, but most were by white scholars. Here was a book written by a Black man, and one who could trace his ancestry to the particular slaves in the book. It seemed a feat of personal and heroic detective work. The book seemed to catch America—all of America—completely off guard. Haley had done something remarkable: He put slavery on America’s front porch. He made it essential to discuss. It had forever torn at the heart and soul of the Black race. And too many whites, when they even deemed to discuss slavery, so often ran behind the ridiculous argument of states’ rights and regional economics, ignoring the horrid brutalities. Jervis Anderson, writing in The New Yorker, hit upon the dissonance so many whites had with slavery:

The condition of uprootedness, the pain of being an outsider in a strange culture and a strange land, has fascinated many American intellectuals for a long time—as well it should, in a nation made up so largely of the uprooted. In articles and books, in classrooms and drawing rooms, they have dwelt upon the tragic nature of that condition. But they seem to have been interested in the subject chiefly as it has affected immigrants; seldom have they been absorbed by the experiences of those who were hauled off and dumped upon this ground to serve as slaves.

James Baldwin weighed in, in a review for The New York Times on September 26, 1976. Baldwin much admired the book, but, as always with him, the article was more than just a review: “Roots,” he wrote, “is a study of continuities, of consequences, of how a people perpetuate themselves, how each generation helps to doom, or helps to liberate, the coming one… It suggests, with great power, how each of us, however unconsciously, can’t but be the vehicle of the history which has produced us. Well, we can perish in this vehicle, children, or we can move on up the road.”

The book seemed to catch America—all of America—completely off guard.

Hollywood was well aware of Haley’s book. It held such high drama; it was a chronicle of high originality; it was, without question, cinematic. The top movie executives had long ignored slavery and deeply probing looks at race in America. This wasn’t A Raisin in the Sun, which revolved around a contemporary Black family’s inner turmoil. This was a Black family that had been kidnapped, enslaved, and ripped apart; this was America’s original sin. Columbia Pictures stepped up to purchase the rights. Their burst of excitement told them it would make a grand movie. Perhaps it would be reminiscent of the lavish attention paid to Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, another sweeping saga (though one, of course, that involved white Italians). But Columbia dithered, and Haley couldn’t get clear-cut answers about plans for filming. He felt he was getting the runaround, that his book might get caught in so-called development hell—circulating among timid executives, only to be forgotten eventually. Haley bought back the rights to his book.

Blaxploitation aside, part of the mindset of mainstream movie execs in the 1970s remained tethered to the Hays Code, that guidepost implemented in the 1930s against film obscenity, but also against racially charged screen portrayals. Of all the films released in 1976—excluding the blaxploitation genre—only two featured blacks in substantial roles: Silver Streak had Richard Pryor in a costarring comedic role, and Sparkle featured three unknown Black actresses in a story about the travails of a singing group. For the Black community, the year when Roots was published had, once again, shown very little representation on the big screen. When turning the dial on television screens, Blacks saw slightly better representation, spotting Black actors here and there, although mostly in sitcoms like The Jeffersons and Sanford and Son.

*

David Wolper, who had made his name in TV documentaries, persuaded Alex Haley to let him buy the rights to Roots. Wolper envisioned a miniseries—a relatively new format, one that offered the potential for more depth and scope than a two-hour feature film—and convinced ABC honcho Fred Silverman to make it. Wolper’s excitement quickly gave way to worry. The American television audience was 90 percent white. There were few major white characters in Haley’s book. Wolper felt the only way he could mount a successful production, ratings-wise, was to cast some white TV stars in the miniseries. “If people perceive Roots to be a black history show,” he said at the time, “nobody is going to watch it. If they say, ‘Let me see, there are no names in it, a lot of black actors and there are no whites’… it looks like it’s going to be a black journal—it’s all going to be blacks telling about their history.”

Television did not have much experience at all at the time in dealing with issues of race. In 1970, NBC aired My Sweet Charlie, an adaptation of a 1966 David Westheimer novel about a Black attorney, Charlie Roberts, who is accused of a murder in Texas. Charlie is forced to flee and comes to hide out in an abandoned house. A young white woman, Marlene, is inside the home, having run away because of the scorn heaped upon her when she became pregnant. The Black intruder shocks Marlene; her bigotry quickly becomes apparent. But as Charlie explains his civil-rights work to Marlene, she begins to soften and, for the first time in her life, begins to understand some of what it means to be Black and fight for justice. Marlene comes to respect and admire Charlie.

Westheimer’s novel was mounted first on Broadway, opening in 1966, and starring Louis Gossett, Jr., and Bonnie Bedelia. It closed less than a month after opening. The novel was seen as interesting, if risky, material for television, and landed at NBC. Network executives chose Patty Duke, a familiar name to television viewers, to play Marlene. Al Freeman, Jr., a highly respected stage and sometimes film actor, was chosen to play Charlie. During filming in Texas, white hooligans let it be known they did not appreciate the subject matter and threatened the production. The atmosphere became so charged and frightening that Texas governor John Connolly had to intervene. When the movie aired, it received fine reviews and multiple Emmy nominations, with Duke winning for her performance. Quite a bit of hate mail was sent to the network. Even a budding nonsexual friendship between a pregnant white woman and a Black man in a 1970 telecast was seen as groundbreaking.

David Wolper cast a bevy of Black actors for Roots, many of whom had become frustrated with their lack of work on the big screen. Among them: Louis Gossett, Jr., Ben Vereen, Maya Angelou, John Amos, Olivia Cole, Georg Stanford Brown, Leslie Uggams, Cicely Tyson, and Lynne Moody. “It was like A Raisin in the Sun,” recalls Gossett. “Wolper wanted the best Black actors in the [Roots] production.” Wolper also cast Lillian Randolph as a slave. Her career had started in all-Black movies decades earlier. She had played a lot of maids. (Her sister, Amanda, who died in 1967, had also been an actress. She had appeared in several Oscar Micheaux films.) Wolper was desperate to find a young Black actor who could handle the role of Kunta Kinte, so pivotal in the book.

After an intensive search, he cast 19-year-old LeVar Burton, a young Californian studying drama at USC. Wolper, in hopes of luring a hoped-for white viewership, went about casting white veterans of weekly television shows: Chuck Connors, Vic Morrow, Robert Reed, Lorne Greene, Sandy Duncan, Ed Asner, Lynda Day George, Lloyd Bridges, and Ralph Waite. Wolper had to swallow the network’s decision not to film in Africa, which would have lent the production verisimilitude but would have been extremely costly. Instead, the production filmed in California and South Carolina.

William Blinn, who had written the teleplay for Brian’s Song, served as script supervisor. Gilbert Moses was hired as one of several directors—and the only Black one—to work on the production. Moses was one of the cofounders of the Free Southern Theater, a group of Black thespians who went throughout the South during the height of the civil rights movement putting on plays. It was brave work. Black farmers—most of them the descendants of slaves—came to see their performances in small country towns. Southern sheriffs often expressed their displeasure, and cast members were arrested for little or no reason. Moses himself eventually left the Free Southern Theatre, unnerved by the death threats he received.

ABC executives began fretting about scheduling after the production wrapped. They discussed airing it in February 1977, the all-important sweeps month, when can’t-miss viewing equals robust advertising revenue. But that idea was nixed: a drop-off in viewers would be financially damaging. There was concern that Southern stations might not air the series and would preempt it with other programming! It was finally decided to air the first episode of Roots on January 23rd.

There were lavish promos on the network’s shows; there were radio spots, and lots of print coverage about the coming telecast.

On January 23, 1977, from neighborhood to neighborhood, city to city, state to state, front doors were closed in Black homes and apartments, as whole families gathered around their TV sets. Children were hushed. And then it happened: a whole family unspooled, their journey beginning in 1750 in Africa, followed by the wrenching kidnapping to America—Kizzy and Fiddler, Kunta Kinte and Chicken George and Tom, Irene and Fanta, Omoro and Nyo. One night turned into two. Three became four. Four became eight. The ritual remained constant, Black families shoulder to shoulder, transfixed. This was wrenching viewing, a graphic depiction of how Blacks had been forced to fight for freedom and dignity within the borders of their own country.

As the week went on, Blacks planned discussion groups to take place in the aftermath of the telecast. Local television crews rushed reporters into Black neighborhoods to do reports on the Roots phenomenon. Grown Black men admitted crying at scenes of slave auctioneering. Black heads of households called their older relatives, asking if they were okay, wondering if the emotion of watching Roots was too overwhelming.

This was wrenching viewing, a graphic depiction of how Blacks had been forced to fight for freedom and dignity within the borders of their own country.

White America also watched. The emotions in their households might not have been as gripping, but they were watching, and learning, and starting to arrive at a different outlook about Blackness and Black people. “They couldn’t realize what they had done,” Gossett says about whites who watched Roots unfold and reveal the scars of slavery. “The sun now shone on the entire situation. Whites had buffered their babies from this.” After the wave of attention from the first night spread and cascaded, America seemed to shut down. Not for a natural disaster, but for a cultural awakening. “By the eighth and final night of Roots, movie theatres in many cities didn’t even try to compete,” The Baltimore Sun reported. “They simply closed their doors.”

In 1977, the majority of critics (more than 95 percent) in American mainstream publications—reviewing for either film, television, or stage—were white. They had never been forced to digest—night after night—such a sweeping look at Black life. “Vistas of jungleland can’t camouflage the intrinsic story of the struggles of the Blacks to preserve their own freedom and dignity,” the Variety critic wrote. “It’s a remarkable presentation.” The New York Daily News called it an “absorbing, beautifully acted epic drama.” Time magazine had some criticism, allowing that slavery was “a crime so monstrous that, like the Holocaust, it is beyond anyone’s ability to re-create in intelligent dramatic terms.”

James Michener, a widely read novelist, was engaged by The New York Times to write about Roots shortly after its airing. “Roots is best comprehended through two comparisons,” he wrote. “It is this century’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a long-overdue romanticization of a pressing problem. It is the black man’s answer to Gone With the Wind, which in its later chapters was sharply racist.”

Writing in The Washington Post, Sander Vanocur, a respected TV journalist, opined that what made Roots “so compellingly unique is that television is finally dealing with the institution of slavery and its effect on succeeding generations of one family in a dramatic form. That effort has been almost absent from our television screens.”

Roots quickly became the most watched TV miniseries of all time. A year earlier, NBC had telecast Gone with the Wind in two parts. At the time, this established a Nielsen viewing record; Roots shattered that record. It was estimated that at least 85 percent of the people with television sets across the country, about 130 million Americans, watched some portion of the telecast. ABC’s decision to run it on consecutive nights paid off royally; another popular miniseries, Rich Man, Poor Man, was broadcast the year before in weekly installments. But the Roots audience expanded night after night. Additionally, Haley’s book was still in hardcover at the time of the telecast, something quite rare, and it became a number-one bestseller.

There were many Emmy Awards for Roots. Many progressive white mayors realized it was a good time to talk about slavery and the ongoing pain it had caused the nation. In many communities, interracial groups planned get-togethers to talk about the series. Interest in genealogical searches erupted across the country. The series also clearly illustrated just how anemic the film industry had been in taking advantage of Black stories. Now there was a sudden appreciation of the Black actors and actresses who had appeared in Roots.

“American actors, whose brilliance is too often overlooked, prove to be equal to their BBC counterparts in this magnificent vehicle,” The Hollywood Reporter wrote of the cast. The movie-theatre owners of America were so stunned and impressed by the success of Roots that they invited Louis Gossett, Jr., and LeVar Burton to their convention in Las Vegas. “They gave us an award,” Gossett says, chuckling at the memory, “because we had kept people out of theatres for the week.”

Many of the actors and actresses in Roots were certain they’d be receiving film offers. Absent that, they’d settle for more television work. “We were so fabulous I thought we would have jobs up the wazoo,” Leslie Uggams said years later. “And there were no jobs. I didn’t get another job until two years later… We were very disappointed, because we had all these accolades; it was like we did our quota, and now that’s it for the rest of time.” Lynne Moody watched her white actress friends go on audition after audition, and has allowed that she fell into a “deep depression” when her career remained stalled.

Louis Gossett, Jr., was one of the few Roots actors who benefited in a substantial way from the show’s success. The role of Fiddler—a slave and mentor to Kunta Kinte—was a tricky one. Gossett imbued it with a canniness and dexterity rarely seen. “I put my soul into the role of ‘Fiddler,’ ” he says. He got more TV roles. A year after Roots, Gossett played the lead role of a doctor in The Lazarus Syndrome, a short-lived TV series. It was a rare occasion when a Black man played the lead. After that, he had a slew of TV movie-of-the-week appearances and the occasional big-screen role.

__________________________________

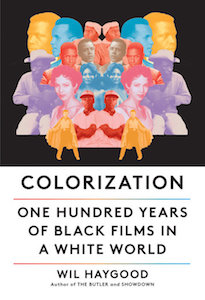

Excerpted from Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World. Used with the permission of the publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Wil Haygood.

Wil Haygood

Wil Haygood is the author of Tigerland, which was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize; Showdown, a finalist for an NAACP Image Award; In Black and White; and The Butler, which was made into a film directed by Lee Daniels. He has been a correspondent for The Washington Post and The Boston Globe, where he was a Pulitzer finalist. Haygood is a Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow, and is currently Boadway Visiting Distinguished Scholar at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.