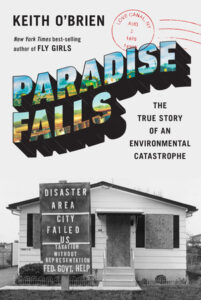

How the Toxic Waters of Niagara Falls Poisoned a Community

Keith O'Brien on Outrage and Resilience In Upstate New York

It was a Sunday afternoon, almost summer in Niagara Falls, and the children from the little bungalows on the east side of town scampered outside to play.

The parents, mostly factory workers and housewives, didn’t follow them. No adults were going to lord over the kids with rules and warnings that afternoon, because everyone knew the LaSalle neighborhood was safe and everyone knew where the kids were going. To the playground, they called it—a rectangular expanse of open land around the elementary school between Ninety-Seventh and Ninety-Ninth Streets in the heart of the neighborhood.

There were some play structures there—a swing set, a slide, and a baseball diamond, too—but mostly the grounds were wild: nearly sixteen acres of grassland, growing in clumps, untended and untamed. Parents sometimes wondered why no one had developed the property, dropped in among the tidy rows of single-story starter homes. It seemed as if someone should have built a real park there years ago. But the children asked no questions because, for them, the land was perfect. The vacant lot to end all lots. A place filled with possibility, and maybe even magic. The older boys, straddling their dirt bikes in tight shorts and white tube socks, told fantastic tales of rocks at the playground that burst into flames, that spontaneously combusted. They said they had seen it with their own eyes.

For decades, almost everyone ignored the problem: health officials and business leaders, the city’s power brokers, and even the local press.

Debbie Gallo—eleven years old, with dark hair and hazel eyes—wasn’t sure what to believe about the fire rocks. Her father was a welder, a son of Italian immigrants, and a Korean War veteran who walked with a limp from the shrapnel that had carved up one of his knees. The Gallos felt fortunate just to own a home in the neighborhood, and Debbie felt lucky that it was this one, on Ninety-Seventh Street. Her little one-story house, white with olive-green shutters, looked right out over the school and the empty land. She could be on the playground almost before the front door slammed behind her, skipping across the street to the open lot. On weekdays, it meant that she didn’t have to walk far to get to her fifth-grade class at the school. On weekends, it meant that her front yard seemed to stretch on like the sea—forever—with friends floating everywhere, coming and going on roller skates and bicycles. This Sunday was one of those days, so Debbie laced up her shoes and headed outside.

It was warm and windy; a spring storm was coming. But Debbie and her girlfriends paid the weather—and the boys around them—no mind. While the boys churned up dust at the playground with their bicycles, clattering here and there on narrow paths carved into the high grass, the girls set about creating something pretty: sidewalk art. At their feet, they began gathering chunks of rock to use as chalk. The rocks were soft and white—“the whitest white I’d ever seen,” Debbie would say later—and best of all they were easy for the girls to find amid the topsoil. Debbie took one in each hand, ran them between her fingers, and then got down on her knees to draw on the concrete.

Later, she couldn’t remember how much time elapsed before her eyes began to burn. Had she been playing with the rocks for five minutes or fifteen seconds? She wasn’t sure. All she knew was that rubbing her eyes only made them worse. As she pulled her hands away, the pain came on like a wave, hot and searing. Her eyes burned as if from the inside. And then she was screaming, and she was running, stumbling across the playground, trying to find her way back to her house on Ninety-Seventh Street through a haze of tears and gauzy darkness. It wasn’t just the pain that worried Debbie, at this point. It was the panic growing inside her, panic over a realization that was hard to explain to her mother back at the house.

Debbie Gallo couldn’t open her eyes. She couldn’t see.

For one brief and scary moment, she was blind.

They didn’t know what they were doing. But they were about to realize that the men in power—the elected officials and corporate executives—didn’t know, either.

That night at the hospital—a short walk from the iconic waterfalls, the tourist hotels lined up along the river gorge downtown, the young newlyweds walking hand in hand in a place still clinging to its reputation as the Honeymoon Capital of the World, and the souvenir vendors selling T-shirts, tchotchkes, and picture-perfect postcards from Niagara Falls—doctors flushed out Debbie’s eyes, pronounced her okay, and sent her home. The next morning, she went to school as usual.

But problems continued at the playground that Monday. Two boys, both third graders, also experienced burning around their eyes and went to see the school nurse. Someone reported the issue to the city fire department, and around 2:30 that afternoon a fire official placed a phone call—not to the school, but to a chemical plant along the Niagara River just east of the tourist district. He wanted to speak to the safety supervisor at Hooker Chemical, the largest employer and industrial taxpayer in town with a sprawling, 135-acre campus on Buffalo Avenue.

Within fifteen minutes, the head custodian for the Niagara Falls Board of Education was waiting in a car outside Hooker’s main gate. The safety supervisor hopped in, and together the pair drove straight for the school, where, working efficiently, they conducted a series of interviews: with the principal, the school nurse, and Debbie Gallo, too. Hooker’s safety expert then walked outside to the playground to inspect the grounds for himself.

It wasn’t the first time Hooker had received phone calls about problems at the playground between Ninety-Seventh and Ninety-Ninth Streets, and it wouldn’t be the last.

The rains had moved in the night before, washing away Debbie’s chalk art and filling the playground with puddles. But it didn’t take long to find the evidence the children had reported. The safety supervisor spotted the rocks near the bicycle racks along the southern wall of the school, collected a sample, and brought it inside to the nurse—just to confirm. The nurse had not only treated the two boys that morning. By chance, she had cared for Debbie the night before in the emergency room. And when presented with the white rocks, this mushy material—whatever it was—the nurse noted that it smelled just like Debbie when she had been scared and blind and crying.

Hooker’s man returned to the plant that afternoon and typed up a one-page report about what had happened that day. Across the top of the page, in large, block letters, the report was stamped “CONFIDENTIAL,” though the safety supervisor made sure to send a copy to the company’s insurance department—just in case. After all, it wasn’t the first time Hooker had received phone calls about problems at the playground between Ninety-Seventh and Ninety-Ninth Streets, and it wouldn’t be the last. Just two days later, a city health official asked Hooker’s safety supervisor to return to investigate a different problem. A metal drum had surfaced this time, belching what could only be described as “rust-colored material.”

For residents, these events were the latest in a litany of curious plights and odd problems. In recent years, people had reported chemical stenches in their basements; floating clouds of acidic fumes that made it hard to breathe; gas leaks that stopped traffic for hours outside the Hooker plant on the river; manhole covers that popped and blew on Buffalo Avenue, hurtling into parked cars like cast-iron Frisbees; and, yes, even rocks that could spontaneously ignite. Several years earlier, in 1966, a city official had confirmed the occurrence, warning that any child who found such a rock should not take it home, but rather submerge it in water or bury it.

The official offered this warning at the time because he understood what he was dealing with, and without question Hooker did, too. The safety supervisor believed he knew exactly what had burned little Debbie Gallo. In his report, he called it benzene hexachloride, BHC—a potent and malodorous poison exceptionally effective at killing boll weevils, spittlebugs, and other pests. It was so exceptional, in fact, that some food manufacturers refused to buy crops from farmers who used BHC in their insecticides. They thought it left an odd flavor in the food itself.

It was so exceptional, in fact, that some food manufacturers refused to buy crops from farmers who used BHC in their insecticides. They thought it left an odd flavor in the food itself.

But that week in May 1972, Hooker’s safety supervisor revealed little about what he knew. He couldn’t say what was in the metal drum when pressed by city officials for an answer; he’d have to get back to them. And he also denied any knowledge of rocks that could burst into flames. He did, however, dutifully inform other important Hooker men about his visits to the playground that week. On Wednesday, three days after Debbie’s trip to the emergency room and just hours after the discussions about the metal drum, a Hooker lawyer called a top city health official and denied any liability.

The health official on the phone found the call to be notable, because he hadn’t mentioned anything about Hooker Chemical being responsible for the incidents. He just wanted to understand what Hooker knew about what was in the ground, he said, to determine if it might be harmful to people, to the kids. Yet despite the interest, the site visits, and the phone calls that week, officials in Niagara Falls kept their silence, and the residents in the neighborhood heard almost nothing about what had happened.

The incident—which had involved the city health department, the city fire department, the city board of education, the school principal, the school nurse, the hospital, children from three families, and multiple people in at least three departments at Hooker Chemical—did what incidents in the city tended to do.

It disappeared, rushing away like water over the falls.

By the end of the 1970s, that changed. Secrets, long kept in Niagara Falls, began bubbling to the surface on the east side of town, seeping into people’s homes, newspaper stories, national headlines, and finally the American consciousness at large. Soon the entire country would know what had happened in this previously unremarkable suburban neighborhood until the name of the neighborhood itself became shorthand for a disaster. No one called it LaSalle anymore. Instead, people knew it as Love Canal—the name of an old, forgotten waterway buried beneath the heart of the neighborhood, a waterway systematically filled with tons of chemical waste, and then erased, as if it had never been there at all.

Secrets, long kept in Niagara Falls, began bubbling to the surface on the east side of town, seeping into people’s homes, newspaper stories, national headlines, and finally the American consciousness at large.

For decades, almost everyone ignored the problem: health officials and business leaders, the city’s power brokers, and even the local press. They said little, or nothing, about the contents in the ground on the east side of town while the people living in the neighborhood, the Gallos and about a thousand other families, went about their lives, unaware of the hazards lurking just beneath their feet, their homes, the school, and the playground where their kids liked to gather. The people in power chose silence, until silence wasn’t possible anymore and this issue, long buried, suddenly had the attention of The New York Times, all three national television networks, the governor of New York, a future vice president, and the White House, too. The president himself was calling.

The decisions made in this little window of time between 1977 and 1980 would change history, spark unprecedented federal action, launch landmark legislation, transform U.S. environmental policy forever, alter the way people thought about their own backyards, and upend the lives of thousands of people living in western New York. But none of it would have happened without a band of ordinary mothers from the neighborhood in Niagara Falls who refused to stay silent, who would not be belittled, who were willing to go to jail to save their children, and who were unafraid—even in the face of the multimillionaires running Hooker Chemical.

Working-class, just like much of the city itself, these women were neither trained nor prepared for this moment, and as a result they made mistakes along the way. They were, some officials suggested, just housewives, a term that was intended to put the women in their place and remind them that they didn’t know what they were doing. But the women wore the moniker, sometimes literally, as a badge of honor.

It was true: they didn’t know what they were doing. But they were about to realize that the men in power—the elected officials and corporate executives—didn’t know, either. And as mothers, the women quickly discovered they had certain qualities that made them more threatening than they could have ever imagined. They knew who they were and what they wanted. They wanted to protect their children. They wanted to leave their homes on the east side of town. They wanted to walk away from the little neighborhood there—the best place they had ever lived, their corner of paradise.

At all costs, they wanted to escape Niagara Falls.

___________________________________

Excerpted from Paradise Falls: The True Story of an Environmental Catastrophe by Keith O’Brien. Copyright © 2022. Available from Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Keith O'Brien

Keith O’Brien is a New York Times bestselling author of four books, including Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball. He has written for The New York Times, Politico, and The Boston Globe. A longtime contributor to National Public Radio, he has appeared on All Things Considered, Morning Edition, and This American Life, among other programs. He lives in New Hampshire. Follow him on Twitter @KeithOB.