How the Schomburg Center Became a Cultural Beacon and Harlem's Literary Sanctuary

Kevin Young on Protecting and Preserving Black History

Born in Harlem, James Baldwin wrote often of his beginnings here, including his reading “every single book” in the transformative space now known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. “I went to the 135th Street library at least three or four times a week, and I read everything here. I mean, every single book in that library,” Baldwin wrote. “In some blind and instinctive way, I knew that what was happening in those books was also happening all around me. And I was trying to make a connection between the books and the life I saw and the life I lived.”

The connection Baldwin made between his life and the lives that the future Schomburg Center contained speaks to the power of the books, history, and culture found there, as well as the center’s rich origins.

Part of the New York Public Library from the start, the Schomburg Center was founded in 1925 as the Division of Negro History, Literature, and Prints, recognizing the changing nature of Harlem after the Great Migration. Yet what truly transformed the division found at the 135th Street Branch was the addition of the stellar collection of Afro-Puerto Rican scholar and collector Arturo Alfonso Schomburg the following year. Today the thousands of books, pamphlets, and manuscripts in Arturo Schomburg’s initial collection have increased to more than 11 million items that, through new acquisitions, programming, and exhibitions, illuminate the richness of Black history, arts, and experience worldwide.

What has become evident in our recent Mellon Foundation-funded work enriching the catalog of what I call Arturo Schomburg’s seed library is that he was not merely a bibliophile or a lover of books but a self-taught scholar, homemade historian, and creator and collector of knowledge. The private collection he assembled was always for public consumption, regularly loaned out to fellow writers, radicals, Prince Hall Masons, and other seekers of knowledge (and, miraculously, regularly returned).

Schomburg’s collection bore witness to the travels and travails of the Black Atlantic, much as he had witnessed firsthand, linking the Caribbean, the broader Americas, Europe, and Africa. Indeed, Schomburg used the proceeds of the sale of his collection to The New York Public Library for $10,000—a goodly sum in 1926, provided by the Carnegie Corporation—to travel to Spain, the motherland of his native tongue, in order to collect more books. He carried them back across the Black Atlantic as the first curator of the Schomburg Center, serving in the role from 1932 until his death in 1938.

Schomburg may now be thought of as the nexus of an informal yet important group of Black librarians, bibliographers, educators, and activists who preserved, protected, and provided access to the rich history of global Black culture—a history that a teacher once told young Arturo didn’t exist. Together with a number of figures—including Catherine Latimer, the first Black librarian in the New York Public Library system, who worked to shape the collections; novelist Nella Larsen, who served as a children’s librarian; and activist Ella Baker and scholar Alain Locke, who transformed the Schomburg Center with education programs in the 1930s—Arturo, also known as Arthur, made the institution a center in all senses of the word.

In the year of its founding, the special issue of Survey Graphic edited by Locke that would later expand into his groundbreaking New Negro anthology, including Schomburg’s famous essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” said as much: “The branch of the New York Public Library which stands on the main cross thoroughfare of Harlem, 135th Street, seeks to be what the Carnegie Corporation would call an intelligence center.” It is no accident that the Schomburg Center was founded in the heart and at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, and it has served as a beacon for nearly a century, keeping the home lights burning and helping to make Harlem a global Black cultural capital.

Schomburg may now be thought of as the nexus of an informal yet important group of Black librarians, bibliographers, educators, and activists who preserved, protected, and provided access to the rich history of global Black culture.

Today, the Schomburg Center still serves as not only a sanctuary for literature, an intelligence center, and a beacon of Black brilliance, but also what scholar Vanessa Valdez has called a liberatory space. Some of this, as Locke noted, is its location: the Schomburg Center remains part of the rich cultural corridor of 135th Street, catty-corner from the crucial Speakers Corner, which saw speeches by Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X; situated directly across Lenox Avenue, now renamed Malcolm X Boulevard, from the training, teaching, and tireless practice of doctors and nurses at Harlem Hospital; and sharing the block with the Harlem YMCA, whose neon sign and Aaron Douglas mural often first welcomed those new to town, from Langston Hughes to Ralph Ellison. Countless brilliant scholars, artists, and activists gathered in the Schomburg Center’s historic reading room facing 135th Street—including Garvey and Zora Neale Hurston, Countee Cullen and Claude McKay, and, later on, designer Dapper Dan and poet and playwright Sonia Sanchez, iconic figures who still frequently return to the center.

After becoming one of the hubs of the Harlem Renaissance, the Schomburg Center is not only where Baldwin read “every single book” but where saxophone colossus Sonny Rollins remembers spending time—both Harlem-born geniuses journeyed around the world from their start in Harlem, with their archives recently coming back full circle to the Schomburg Center in 2017.

Harlem is where Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis met Harry Belafonte, becoming actors and activists together, and where both Ann Petry and Gertrude Hadley Jeannette acted before becoming writers, all in the Schomburg Center’s American Negro Theatre, still housed in what is now the courtyard level. Harlem is where filmmaker Oscar Micheaux plotted, filmed, and projected Black life for popular consumption and activist Malcolm X transformed from his troubled beginnings to become our Black Shining Prince. Harlem is where, following in the footsteps of his Garveyite grandfather, Fred “Fab 5 Freddy” Brathwaite makes his home, continuing as a hip-hop pioneer and ambassador—having united downtown and uptown culture and introducing, influencing, and producing many of hip-hop’s earliest innovations.

All of these artists and activists have become part of the Schomburg Center’s broader Home to Harlem initiative, their archives recently returning home to Harlem to live and prosper nearly 100 years after Schomburg’s seed library arrived here.

The “vindicating evidences” that these figures assembled gave birth to the field of Black Studies, advanced adult education, and changed Black theater and film history—all around the intellectual and artistic hub that would become the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

__________________________________

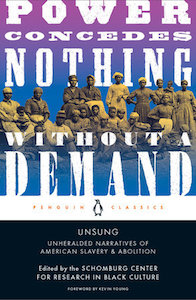

Excerpted from Unsung: Unheralded Narratives of American Slavery & Abolition. Edited by Schomburg Center and Michelle D. Commander. Used with the permission of the publisher, Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Foreword copyright © 2021 by Kevin Young.

Kevin Young

Kevin Young is the Andrew W. Mellon Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. He previously served as the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Young is the author of fourteen books of poetry and prose, including Brown; Blue Laws: Selected & Uncollected Poems 1995-2015, long-listed for the National Book Award; Book of Hours, winner of the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets; Jelly Roll: a blues, a finalist for both the National Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poetry; Bunk, a New York Times Notable Book, long-listed for the National Book Award and named on many “best of” lists for 2017; and The Grey Album, winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize and the PEN Open Book Award, a New York Times Notable Book, and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. The poetry editor of The New Yorker, Young is the editor of nine other volumes, most recently the acclaimed anthology African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and was named a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2020.