How the Pandemic Has Changed the Way We Think About Solitude and Loneliness

Four Writers from The Lonely Stories Share Their Experiences

When I was a child, I spent a lot of time alone. I was often sick with chronic sinus infections, undiagnosed migraines, chronic fatigue syndrome, and anxiety. As a result, I strongly relate to and empathize with the loneliness of isolation. Now, as an artist and writer, I relish and often crave solitude. I loved the idea of conjuring a book that would tease out the ways in which alone time can be both maddening and joyful.

The Lonely Stories began with a question inspired by Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights. He writes, “What if we joined our sorrows? What if that is joy?” While working on The Lonely Stories, I rephrased this in my mind as, “What if we joined our loneliness? And what if THAT is joy?” To me, acknowledging our vulnerabilities—including our anxieties about being alone—can be a stepping stone to the joy that comes from feeling relieved. It can remind us: I’m not the only one who feels this way.

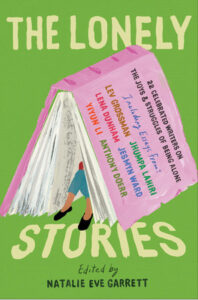

The book is a collection of 22 personal essays from celebrated writers illuminating the experience of being alone. I embarked on the book before the pandemic, and much of it explores types of aloneness that existed long before and will continue to echo in the pandemic’s aftermath. For me, in the wake of living through a period of collective isolation, the premise of the book resonates even more strongly. My hope is that the reader will find these stories as transporting and unlonely as I do.

Four contributors to The Lonely Stories—Maya Shanbhag Lang, Emily Raboteau, Lev Grossman, and Amy Shearn—chatted with me about how the pandemic shifted their way of thinking about being alone, their favorite places to be alone, favorite things to do when they’re feeling lonely, and so much more.

–Natalie Eve Garrett

*

Natalie Eve Garrett: Talk to me about how the pandemic changed your way of thinking about solitude and loneliness. Do you see it differently now?

Emily Raboteau: I have never felt more lonely than during the pandemic when half my building fled the city. Conversely, I have never craved solitude more than during those months when I couldn’t escape the company of my young children or the three rooms of our apartment, except to the bathroom to cry. I like what May Sarton said about loneliness being the poverty of self and solitude, the richness of self. I have not experienced the richness of solitude in a long time.

Lev Grossman: I strongly empathize with this. I feel like there have been two pandemics happening at the same time, one characterized by a surfeit of loneliness and the other by a dearth of solitude. I’ve mostly had the second kind, but my brother, who lives by himself, had the first kind. We’re twins, and his house is only about a mile from mine, but our lives are indescribable to each other.

Maya Shanbhag Lang: I love that line from May Sarton, whose work—reflective, candid, searching—speaks to me deeply. And I relate to what Lev said about loneliness and solitude: the former feels excessive and the latter feels scarce. Until the pandemic, I’d always prized solitude. I’m divorced. On days when my daughter would go to her father’s place, instead of relishing my time to myself as I normally do, I felt like I was staring into an abyss. It was paralyzing. Meanwhile I felt guilty because nearly all of the women I know desperately needed a break and would have given anything, as Emily said, to have some time to themselves.

I have never felt more lonely than during the pandemic when half my building fled the city.

Amy Shearn: This is a tricky one for me to answer, because like Maya, I’m divorced and I coparent my kids with my ex. Before that, like Emily and Lev and I think most parents of young children, I was used to never having any time alone. So throughout the pandemic, I’ve related both to parents who’ve felt like they’re losing it, because being alone with kids can be catastrophically exhausting, and to single people who felt, especially in those first months, painfully lonely and touch-starved.

And you know what—even though I was so grateful for my times of solitude, I also embarked upon some pretty chaotic pandemic dating. You have to understand how in New York City there was this stench of apocalypse, and that plus living alone for the first time in my adult life, led me to, let’s say, prioritize connecting with other adults. Sometimes I just felt that if I didn’t touch another person’s body, wasn’t touched by another person, I would cease to become a human being. Sounds a little dramatic I know, but it really did feel that way.

Natalie Eve Garrett: How would you describe the difference between solitude and loneliness?

Maya Shanbhag Lang: Solitude is a choice; loneliness gets foisted upon us. When we feel lonely, we feel powerless and without agency. Perhaps it’s like the difference between leaving and being left. For me solitude is, ideally, an embrace: I am choosing time with and for myself. When I feel lonely, there’s a kind of helplessness to it.

Amy Shearn: I love that distinction. To me it’s also about a sense of connection, which can mean connection to myself. The way I see it, loneliness has almost nothing to do with whether or not I’m around other people. I’ve been at my loneliest—isolated, misunderstood, alone—while surrounded by people. Solitude is often when I can reconnect with myself, which is a profoundly unlonely experience.

Natalie Eve Garrett: I completely agree with that. I think of solitude as the art of being at ease and at home within oneself. Whereas I associate loneliness with absence, a feeling of lack. I’m curious, do you have a favorite place to be alone?

Emily Raboteau: I like going to the movies by myself.

Maya Shanbhag Lang: I love the solitude I experience on the page (writing or reading) and while working out (I’m a weightlifter), when the physical world disappears. There’s a kind of transcendence of space and time.

Sometimes I just felt that if I didn’t touch another person’s body, wasn’t touched by another person, I would cease to become a human being.

Lev Grossman: Last March I took a job that involved travel. I had to go to a town in Colorado and stay in a small hotel. It was the first time since the pandemic started that I’d been alone—like really, reliably alone, where I could go to the bathroom or take a shower or sit at a desk for an hour and know that nobody else would walk in or look in or yell up the stairs that they needed help with Legos. It wasn’t even an especially nice hotel; the room was tiny and the bed took up most of it, but when I closed the door and put down my bags, it was an emotional moment. Everything came out. I’ll never forget it. I was there for a week. I thought I was in heaven. But then after a day and a half, I started getting lonely.

Amy Shearn: I love to travel alone. I like going out to eat alone, going to museums alone, sitting in cafes alone, going for long walks alone. A thing I love about cities is that you can be alone in lots of places and also be surrounded by people, and often have chance interactions and form unexpected connections in ways that you’re not open to if you’re already with someone. Being alone allows you to be less lonely and more connected, if that makes sense.

Natalie Eve Garrett: Would you be willing to share any of your cherished coping mechanisms for loneliness?

Amy Shearn: I’m sorry to say something so #basic, but when I feel lonely I reach out to friends. I’m lucky to have a lot of good friends who are there when I need them. We meet for drinks and share meals and coparent during hard stretches—once a friend and I even vacationed together with our kids—and often we text and talk on the phone like teenagers. Well, probably not like teenagers. Real teenagers probably talk via Snapchat, or maybe something new I’ve never heard of. The point is, even in adulthood, deep and soulful friendship might be the real key to never being too lonely.

Emily Raboteau: Listening to books, podcasts, or music transports me out of feeling self-consciously lonesome. Cultivating seasonal native plants makes me feel connected to the land.

Maya Shanbhag Lang: This will sound so odd, but when I’m in the clutches of loneliness, I head to the freezer and grab a handful of ice. The sensory shock of it jolts me back into being. It usually takes a minute before I register the cold because I’m so in my head that I need something to put me back in my body. It’s astounding to me how little time we spend in our bodies. Music also helps. It’s like having another road appear or an off-ramp materialize, a quick access point to a different state of being.

Natalie Eve Garrett: I love that, Maya! The things that offer me the greatest relief from loneliness are also the things that bring me into the moment, and remind me of my senses. My children’s laughter. Petting my puppy. Listening to birdsong in the woods. Baking.

Lev Grossman: A boring answer, but meditation helps.

Natalie Eve Garrett: What surprises you the most about loneliness?

Lev Grossman: I used to think of myself as a solitary person. I think there’s a certain cultural trope of the macho solitary male wanderer, the lone wolf who needs nobody but himself—Han Solo. I thought that was me; really I thought I enjoyed loneliness. Then I went and lived by myself for a few months in the woods in Maine and got a taste of the real thing, and I collapsed completely, almost immediately. It turned out I’d never really been lonely before, and I needed other people so desperately. I couldn’t keep a stable sense of who I was when I was alone. That was a surprise.

Maybe if you feel lonely, make something. See how it goes.

Emily Raboteau: I did not understand in my youth that loneliness would only dissipate in the company of other people if they were the right people.

Maya Shanbhag Lang: Yes! It’s possible to be with someone and feel alone or by oneself and feel wonderfully enriched, a pleasant sense of company.

Amy Shearn: Completely. People can make you lonely, and solitude can feel companionable. Maybe this is why I’m often surprised by people who can’t sit with themselves, who not only don’t feel the need for solitude but actually actively hate it. I’m perpetually surprised at the extent to which people will go to try to inoculate themselves against loneliness. That said, my “solitude” is full of a lot of people: my kids, dates, friends. And my time alone helps me to appreciate and absorb all of that more. We need both! Or I do anyway.

Natalie Eve Garrett: Talk to me more about things that amplify—or diminish—your experience of loneliness.

Emily Raboteau: The only place I’ve been able to cultivate rich solitude in this era is my garden.

Maya Shanbhag Lang: I love the idea of cultivating rich solitude. An ongoing lesson for me is that self-care doesn’t always seem appealing at first. That term has been hijacked by capitalism. We’re told that we can buy a brownie (or a lifestyle) and feel better. But really showing up for ourselves and caring for ourselves is altogether different. It’s a decision. Once we make that decision, it can manifest as cooking a meal or going for a walk, but for me, at least, those things don’t yield rewards unless I first make the choice to be kind to myself.

Natalie Eve Garrett: I love that! Also, earlier, Maya, you mentioned the ways in which you cherish the solitude you experience while writing.

Amy Shearn: Yes! We haven’t really talked about the role of solitude in creativity. We’re all writers, obviously, and in order to write, you have to have time alone. But while you need some solitude in order to create, oddly enough, when you are creating, you’re never really alone. I feel profoundly unlonely when I’m writing. How could I feel alone when all these characters are talking and walking about and doing their things? I don’t know if it works the same way for everyone, but maybe if you feel lonely, make something. See how it goes.

__________________________

The Lonely Stories (ed. Natalie Eve Garrett) is out now from Catapult.

Natalie Eve Garrett

Natalie Eve Garrett is an artist and a writer. She's the editor of Eat Joy: Stories & Comfort Food from 31 Celebrated Writers and The Artists' and Writers' Cookbook: A Collection of Stories with Recipes. A graduate of Yale University and the University of Pennsylvania's School of Design, Natalie lives with her husband, daughter, and son in a town outside D.C.