How the NY Post and the NY Daily News Turned Victims Into Criminals

Heather Ann Thompson on the Role of Tabloid Journalism in Shaping the Racist Narrative of the 1984 Bernie Goetz Subway Shooting

Getting word that four Black teenagers from the South Bronx had been gunned down by a white guy on the New York City subway was like Christmas come early for both the New York Daily News and its newly determined competitor, Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post. Both papers hurried to make the most of this dramatic event, no matter how little reporters actually knew about the identity of the gunman or his motives for shooting four people. Subway riders were one of their largest group of readers, and this was a story they would want to devour right away. Indeed, as veteran New York Post reporter Cynthia Fagen remembered, “If you went into the subway, everyone was reading a newspaper. It was either the Daily News or the New York Post.”

The Daily News provided the earliest and most dramatic coverage, with front-page headlines that blared “‘VICTIM’ ON SUBWAY SHOOTS 4,” and “A FANTASY COME TRUE: DEATH WISH GUNMAN CAPTURED CITY’S IMAGINATION,” and “PREY TURNS PREDATOR.” Not to be outdone, the Post was soon dubbing the shooter the “Bronson Copycat” and the “Death Wish Gunman” in equally salacious bannered articles. Within days, the Post even created a logo to accompany all of the articles on the shooting: a hand holding a gun, against the backdrop of a dark subway tunnel, with the text “Death Wish Vigilante.” Over the next few months, these two tabloids would produce an immense volume of increasingly inflammatory reports on this shooting.

What perhaps mattered more than the incendiary headlines or the sheer number of stories both tabloids immediately devoted to this event, however, was the misinformation each was also imparting to the public. The very first piece published by the Daily News, for example, claimed that the “men” who had been shot, including “Troy Canty, [age] 25,” were all “armed with screwdrivers.” Another piece doubled down on its reporting that the teens had been armed, noting that they had actually been “carrying sharpened screwdrivers.” Such coverage also showered the shooter with praise. As yet another Daily News article insisted admiringly, the gunman was, for New York, “an instant hero, a true-life Charles Bronson, a subway vigilante with his own style of justice.”

What perhaps mattered more than the incendiary headlines or the sheer number of stories both tabloids immediately devoted to this event, however, was the misinformation each was also imparting to the public.

The Post‘s stories similarly revered the shooter, noting that his “courteous and unrattled style was dramatically similar to that of the character played by [Charles] Bronson.” He had, after all, taken the time “to help the hysterical women to their feet and escorted them to another car before fleeing.” Meanwhile, the Post also noted repeatedly, these young men had “extensive criminal records,” and at least one of them, the main offender, Troy Canty, was “twenty-three” and thus was hardly a youngster who was merely horsing around with his friends on the 2 train.

This tabloid also asserted confidently and regularly that the screwdrivers found on the subway teens—sometimes described as “screwdrivers with sharpened tips,” or “sharpen[ed] screwdrivers,” or as “long, sharpened screwdrivers”—were being brandished first to intimidate and then “to rob” the man who instead shot them.

Even the nation’s paper of record, the highly respected New York Times, soon jumped on this story line. When its reporters first learned that two of the boys had been carrying screwdrivers, they simply noted it. Soon, however, the paper was also implying that the four Black youths on a NYC subway car had been shot because they had been carrying these “sharpened” screwdrivers. Almost overnight, this detail became so accepted as fact by the national media that even Time magazine was reporting on the sharpened screwdrivers. The implication was clear: The ostensible victims in this situation were really the villains.

The information that the teens had been carrying screwdrivers came originally from the NYPD and Transit Authority. At no point, however, did either law enforcement body step in to dispel the rumor that these objects had been sharpened, nor did they ever share the important information that such tools were commonly carried by poor people to jimmy open the coin receptacles in public washing machines, cigarette dispensers, arcade games, and more.

That said, some officers and detectives were unwilling—at least initially—to cast suspicion on the shooting victims themselves. When he finally emerged from the bloodied subway car the night of the shooting, NYPD officer Peter Smith, for example, conceded to a reporter that the gunman “possibly” could have construed the teens’ actions as “harassment,” but it was his impression that they had just been “fooling around with the guy.”

Similarly, the first police officers and detectives from both the NYPD and the Transit Authority who interviewed the wounded boys in the hospital tried to listen to their account of what had actually happened, rather than just assume they deserved their devastating injuries.

Late on December 22, for example, mere hours after the shooting, detectives visited Barry and James, both of them still in the ER with conditions listed as critical, to record their official statements. Still in shock and traumatized, the teens tried their best to recount the events that had, inexplicably to them, led to the eruption of gunfire. The detectives also asked them to describe the shooter, but according to the detective’s report, James, at least, “could not give me any description of the perpetrator, stating that he only knows the guy was white.” In an additional report filed on this interview, the teens were listed clearly as “victims.”

Detectives also headed to St. Vincent’s that night to interview Troy Canty and Darrell Cabey, both of whom were out of surgery but still in very bad shape. Troy refused questioning, but Darrell was successfully interviewed, and here too law enforcement seemed to have no doubt that he was the victim; the report they filed explicitly identified Darrell as such. Notably, Darrell had also seemed unable to provide much insight regarding the reason he had been shot. When Detective Richard Commesso asked him when he had become aware that “a rip-off was going to take place,” for example, Darrell responded emphatically that he had no idea “what was going down” just before the man started shooting.

The next day, Darrell was interviewed again, this time by Detectives Michael Clark and Daniel Bronte. This exchange yielded them two critically important pieces of new information. First, Darrell stated without hesitation that “the white man then went to shoot me. He missed with the first shot. He then fired a second shot hitting me in the back.” He also gave a clear description of the shooter: “a white male in his thirties, with blond hair, Thin Build 5’10-11.” What’s more, he went on, the man had “Clear Round Glasses, Jeans, and [was] armed with a silver revolver.” Clark and Bronte’s report also listed Darrell Cabey as “Victim Gunshot.”

Only one day after that, on December 24, however, law enforcement’s attitude toward the teens seemed to shift markedly, with neither the NYPD nor the Transit Authority now being willing to just accept their initial statements. On this Christmas Eve, law enforcement higher-ups decided to send Detective Clark back to St. Vincent’s, this time with another interviewer—Detective Charles Penelton of the Transit Police—to question Darrell again and to get Troy to talk for the first time.

Darrell didn’t tell these detectives anything new that should have made them doubt the initial account, but it was clear that at least Penelton came away dubious. The report that he filed dutifully acknowledged that the statement he had taken from Darrell “was consistent” with that which had been recorded the day before. But whereas those first detectives who spoke to Darrell had designated him as a “victim” on the official police report, Penelton did not follow suit.

Clark and Penelton then went to see if they could get Troy Canty to open up at about 2 :10 PM that same afternoon. Troy was leery, noting disgustedly, and correctly, that law enforcement had decided this time to send a Black detective, Penelton, hoping that this would put him at ease enough to finally talk. As if on cue, Clark, the white detective, left the room. But Troy was still on heavy pain medicine, “had tubes coming out of his chest going to machines that were sucking blood out of his lungs,” and was having a hard time staying awake. Still, he eventually did agree to speak to Penelton. The detective’s version of what Troy said that afternoon, however, would in time be hotly contested. In Penelton’s view, Troy was no victim—he had provoked his shooter.

*

Meanwhile, and indicative of how hard it now was for the NYPD to imagine that four Black teenagers could really be innocent in all of this, back at police headquarters a great deal of time was being expended on determining how many crimes each of the teens might have committed before they had boarded that train.

Their efforts were not in vain. In the past few years, the four boys had indeed accumulated a slew of misdemeanor summons for a range of petty offenses—some dating back to October 1981, and others recorded as recently as November 1984. As these were low-level offenses, the officers on the scene had merely issued summonses for them to appear in court. But for poor teenagers in this city, with no means of paying the fines the judge would require if they showed up, skipping such court dates was commonplace. All of these teens had in fact ignored their notices to appear.

Notably, however, no prosecutor had yet asked the court to issue bench warrants for their arrest—until now, less than one week after a man had shot them.

Two judges’ decision to hand down a blizzard of bench warrants against these teens—on December 27, 1984, on New Year’s Day, and again on January 2, 1985—would have an incalculable impact on the subsequent media coverage of the subway shootings, and in turn, on the way that countless New Yorkers and the nation more broadly would come to understand all that had gone down on the 2 train three days before Christmas.

When Judge Alan Marrus decided to issue a bench warrant for Troy Canty’s arrest a mere five days after he had been rushed to the ER, he cited an earlier incident of “breaking into a video game machine at Boyle’s Pub” on 23rd Street. According to this warrant, in the course of stealing $14 in quarters, Troy had done “$250 in damage to the machine.” He faced charges of larceny and malicious mischief, and should he not now appear in court, he would be arrested.

A few days later, Judge Stanley Katz went even further. It was New Year’s Day 1985 and the courts were officially closed, but he nevertheless showed up to issue a collection of ten bench warrants against the teens, each one also stemming from low-level misdemeanors. These included two more warrants against Troy Canty, for “failing to pay a $10 fine for riding between subway cars” (October 1981) and “failing to respond to a summons charging him with subway trespass” (November 1984); three against James Ramseur, for disorderly conduct and marijuana possession (both from February 1984), as well as for failure to answer a summons for subway trespass (May 1984); three for Barry Allen, all for failing to respond to summonses for subway trespass (two from 1983; one from 1984); and two for Darrell Cabey, also for “failing to answer summonses” and “disorderly conduct.”

The sudden and aggressive issuing of such warrants was not without controversy. A Manhattan criminal court judge named Edward McLaughlin, who was then tasked with overseeing Troy’s case regarding breaking into video machines, simply could not understand why Marrus was so determined to go after the very people that the Manhattan DA’s office would most need help from when trying to build a case against the shooter—should they ever find him.

Judge Marrus, however, refused to back down. He argued that Troy’s “extensive” criminal record indicated that he “poses a danger to the community.” Marrus insisted that Troy Canty should be arrested the instant he was allowed to leave the hospital but also that his bail be set at $1,000—an amount this teen would never be able to pay.

Nowhere in these warrants was there any indication that the boys were violent or dangerous. If anything, the minor charges within them could well have been used to corroborate the boys’ claims that their only plan that day had been to jimmy open some arcade machines. Nevertheless, this flood of paperwork would serve only to confirm everything the reporters had already been saying: These were thugs whom the “Death Wish Shooter” had been right to take down. So many warrants were indisputable proof that the shooter had been right to fear for his life.

The fallout from this on the teens themselves was immediate and alarming. Even though they were still in the hospital, under the twenty-four-hour care of nurses and doctors, the boys, as well as their families back in the South Bronx, were soon receiving a torrent of ghastly threats. Callers promised, among other things, that they were “going to come by and ‘finish the job.'” In another instance, someone rang the Allen family to say chillingly that they had “heard the good news about Barry being shot.” Barry’s little sister, who answered the call, was terrified.

And then there was the hate mail that flooded the mailboxes of the boys’ families, after both the Daily News and the Post had published their addresses.

No matter what these families said or did, however, the press continued to sell its own narrative of the shootings.

Some of the worst messages came to the Cabeys in the form of “get well soon” and “Merry Christmas” cards. One such festive piece of holiday stationery, addressed “To Darryl Cabey, the cripple N-,” expressed the wish that he might “be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of [his] life.” Another gaily decorated card addressed to Shirley Cabey read, “I hope your son is crippled for life to remind you that it was your responsibility to raise your child to be a decent human being and not an animal.”

Darrell’s mother seemed to be a particular target of this vitriol, receiving awful letters such as: “Mrs. Cabey, It’s a shame the day you give birth to that no good son [that] the doctor did not choke him with the umbilical cord and kill him.” Yet another shrilled, “It’s too bad [the gunman] didn’t kill the lot, they’re all rotten+ so are you…[He] is a decent human being pushed to the limit by the likes of your offspring.”

This mail wasn’t just ugly. Like the phone calls, it could also be downright threatening. One letter addressed to Darrell said coldly, “Your days are numbered. And when your kind are removed from our streets, New York will fulfill its destiny to be the greatest city of all times.” Others expressed similar sentiments such as “I am glad Daryl is paralyzed…I’m so sorry that the other 3 can’t join him,” or ”I’m sorry he didn’t kill you all” (the latter from a “Correction Officer”). Yet another envelope contained only a sticker, with a swastika logo and the words “Deport Sp-s, N-s and Jews!”

Even when it became clear just how much hate they were enduring, neither the boys nor their families garnered much sympathy from their fellow New Yorkers. At the forefront of the public’s consciousness, in no small part thanks to the tabloids’ coverage of this event as well as the warrants they now faced, was the certainty that Troy, Barry, James, and Darrell were indeed a “danger to the community,” and therefore they deserved nothing more than what the shooter had already given them.

Seeing this degree of racism and hatred unleashed on their children and themselves was beyond painful to the families. Just as Shirley Cabey had rushed into Manhattan upon learning that Darrell had been shot, so too had the other boys’ parents. They had also been living hour by hour, just hoping that their kids would be all right.

Troy Canty’s relatives arrived at St. Vincent’s just as bewildered and scared as the Cabeys. On a typical day, Troy would have been getting ready to go to sleep on one of the two sets of bunk beds that had been squeezed into the kids’ bedroom at home. Instead, he was in surgery. Troy’s older brother Carl just couldn’t get his head around it. To be sure, Troy was no saint, Carl would acknowledge to reporters. And he was someone who needed to take drugs to deal with his anxiety. But he was not a thug, and didn’t deserve this. Troy’s dad, forty-eight-year-old Edward Canty, agreed. There was no way Troy was trying to rob anybody.

At Bellevue, Bessie Ramseur had also been unable to comprehend why this had happened to her son, James. “My son may have been rowdy and loud sometimes, but he never did anything to hurt people,” she would insist. Barry Allen’s mother, Mary, felt the same disbelief that her son had done anything to warrant being shot. Almost desperately trying to stress this point to reporters, she would even welcome them into her home, pulling out a scrapbook she had made “showing four academic awards her son won in 1978 and 1979.”

No matter what these families said or did, however, the press continued to sell its own narrative of the shootings. On some level, these parents and siblings understood exactly what was transpiring, and had little doubt as to why it had been so easy to villainize their loved ones. When asked about the public’s reaction to the gunman and victims such as his son, Troy Canty’s father didn’t hold back:

I think he’s a crazy man. He has to be. But white people don’t care too much about blacks….If they get him, they are not going to bother him too much….The kids are black and poor, and [the authorities] will believe everything he says, and nothing the kids say. That’s the way it goes….When black people get shot by a white man…That’s what people will say…That they were about to rob someone.

Barry Allen’s sister Patricia viewed the situation similarly, though she still couldn’t quite fathom how quickly people had sided with the man who had shot her brother in the back. “I am very angry at those people,” she said. Those who knew James Ramseur also found the way in which his shooter had been celebrated perhaps predictable but nevertheless hard to process. As one of his close friends said disgustedly, the “people who are praising the gunman are ‘sick.'”

To Troy’s brother Carl, it was all pretty simple, actually. As he put it, people had just decided that “it was four ghetto kids that wasn’t gonna amount to shit anyway. What the fuck are we gonna waste our time with him for?”

Still, this was a hard pill to swallow. Many kids from the South Bronx, including Troy and even Carl himself, had committed their share of petty crimes. But they had never harmed people. Maybe “we was criminals,” Carl Canty said sadly, “but not hurting criminals.” ”I’m not gonna rob you,” he continued, ”I’ma steal from the supermarket.” Sure, some out there were robbing old people, choking people, robbing them, beating them up, taking their money, but Troy just wasn’t like that.

There was, however, one person still at large who had very much hurt people. Whether that man could ever be found, let alone brought to justice, remained to be seen.

__________________________________

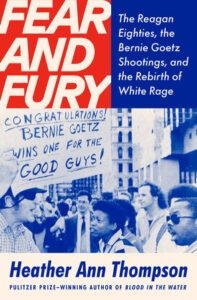

Excerpted from Fear and Fury The Reagan Eighties, the Bernie Goetz Shootings, and the Rebirth of White Rage by Heather Ann Thompson. Copyright © 2026. Available from Pantheon Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Heather Ann Thompson

Heather Ann Thompson is a historian and the author of Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy, which won the Pulitzer Prize and the Bancroft Prize. She is also the author of Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City. Thompson has written about the criminal justice system for myriad publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time, Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. She has served on the National Academy of Sciences blue ribbon panel that studied the causes and consequences of mass incarceration in the United States, co-runs the Carceral State Project at the University of Michigan, and has been the recipient of numerous honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whiting Creative Nonfiction Grant, and a Racial Justice Fellowship from the Carr-Ryan Center for Human Rights at Harvard University. Thompson has also served as a historical consultant for film and television, including on the Oscar-nominated feature documentary Attica.