How the First Ever Christian Rock Album Led to the “Jesus Movement”

Josiah Hesse Explores the Intersection of Family History With the Rise of the Religious Right

1977

As Janet Chastain sat with her parents, watching Jimmy Carter’s inauguration on the living-room TV, she wanted to scream.

It wasn’t that she was unhappy that Carter—America’s first evangelical president—was being sworn in on his old family Bible. At sixteen, Janet was too young to vote for him, but she had volunteered on Carter’s campaign, canvassing her neighborhood for the Democratic nominee. Her parents were old-school Democrats, raised on farms saved by FDR’s Agricultural Adjustment Act, and were proud to now have a “social gospel” Christian in the White House. Which was part of the reason Janet (my future mother) had volunteered for him.

Otherwise, she felt invisible much of the time.

The result of an unplanned pregnancy, born several years after her three older siblings, Janet had always felt disconnected from the momentum of her family. They’d all grown up on the family farm, which meant a hard life of round-the-clock labor and no indoor plumbing. She was only an infant when her father sold the farm to his brother in 1960 and moved them into a house on the north end of Mason City.

While generations of Chastain families kept struggling as farmers, their new family business of selling farm machinery and repairing silos did very well. Midwestern agriculture played an increasing role in global trade and U.S. foreign policy, so small family farms were encouraged by Nixon’s secretary of agriculture to “get big or get out” and “plant fence row to fence row.” Farmers were up to the task, because the value of their land was skyrocketing, and many bankers encouraged them to take on large amounts of debt to increase the size of their operations (a move that would come back to haunt them during the farm crisis of the 1980s).

With her family business in high demand, Janet’s middle-class childhood provided her with a level of comfort and security never known to her parents or older siblings. Consequently, she was dismissed as spoiled and undeserving of attention by her brothers and sister, who were entering high school, the army, and parenthood, respectively, before she’d reached adolescence. They often accused her of being “too much,” of exhausting them with her incessant questions, her need to drill down into every subject, analyzing all sides of an issue until there was no room for a single, coherent perspective.

There was a rich marketplace of spirituality for California bohemians. And, for many, the answer was Pentecostal Christianity.

On the other hand, what made her an obnoxious little sister served her well in school.

Janet’s mother, Marilyn, was deeply insecure about having never finished college herself, and—newly flush with cash—offered to pay for four years of her children’s higher education (which cost, on average, $740 in the late 1970s). Marilyn had attended one year of a Methodist college in Chicago in 1947, and another year at Waldorf University in Iowa, but marriage, farming, and motherhood prevented her from finishing. And, one after another, her children followed the same path of completing one or two years of college before dropping out and launching families of their own.

She viewed Janet as her last chance for academic salvation and forbade her to engage in anything not related to school or church, and even gave her a hearty allowance so she wouldn’t be distracted by a part-time job. Grateful to have, finally, a morsel of attention (even if it was anxiety-fueled discipline with little positive reinforcement), Janet plunged herself into academia, developing an insatiable hunger for a wide range of topics.

“She was into everything,” her childhood best friend would tell me, years later. “Speech Club, Forensics League, Foreign Exchange Club, she was in plays, very social—just wicked smart. She picked up on things so quickly, much faster than anyone else.”

On the debate team, Janet found deep satisfaction in being able to argue two sides of the same issue, bathing in the nuance of complex affairs like prison reform or a one-world government.

At fifteen, she learned fluent Spanish and traveled to Argentina for a three-month exchange program; her trip happened to coincide with the 1976 right-wing coup d’état that ousted Isabel Perón, which gave her a visceral lesson in the fragility of democracy, the threat of economic inflation, and the fine line between revolution and genocide. As challenging and treacherous as international politics could be, Janet didn’t want to return to North Iowa. She dreamed of one day being a U.S. diplomat, traveling the world, negotiating peace treaties, and boosting foreign economies. Janet couldn’t wait to finish high school and climb the ladder of higher education, narrowing her choices to either the liberal arts Macalester College in Minneapolis or the University of Chicago—both renowned for their international relations programs.

She expected a certain level of excitement and curiosity from her family when she came home from Argentina, but her grown siblings were still sucking up all the air. One brother was getting married; the other, traumatized by his stint in Vietnam, announced that God had told him to become a Mormon. Her sister, married to an Open Bible pastor, accused this brother of sacrilege, saying he would burn in Hell while they watched from Heaven.

The one thing all three of her siblings did have in common was a gravitation away from the Democratic Party of their parents; instead, they embraced the “new right” of conservatives like William F. Buckley, Bill Bright, and Ronald Reagan, who they believed would have been president if he hadn’t lost the nomination to Gerald Ford.

In the years to come, my grandmother would repeatedly ask the world what she had done to wind up with four children who voted Republican. For her and so many working-class Christian families in America, there was no better manifestation of the teachings of Jesus in government than FDR’s Second Bill of Rights speech in 1944, promising economic justice through adequate wages, Social Security, education, housing, medical care, and restrictions against monopolies.

They were part of a long legacy of politically active Christian liberals, who throughout history have been at the forefront of progressive movements like the abolition of slavery, child-labor laws, women’s suffrage, and civil rights.

The election of Jimmy Carter was the apex of leftist Christianity in America.

There were forty to fifty million evangelicals in America at the time, but most political journalists were unfamiliar with the term before that Democratic candidate, who would often refer to his “born again” spiritual experience. “The most important thing in my life is Jesus Christ,” Carter said in a campaign speech. Carter was a Sunday-school teacher in the Southern Baptist Convention, a denomination that had favored Republican candidates since 1948, but almost 60 percent of which went for Carter in the ’76 election.

As a teenager with a hyper-analytic mind, Janet gorged on as much information and ideas as she could get her hands on; she felt pulled in several directions at once, since her worldview refused to solidify into any one, singular identity.

Feminism was a provocative label at the time, but it felt right to Janet. Looking at the framed pictures of weddings and newborn children of her siblings, which were hung with pride above the TV, she thought it was profoundly unfair that a woman’s only measure of success was marriage, kids, and housecleaning. Which made her all the more humiliated after she tried, and failed, at that very endeavor.

The previous fall, desperate for validation from her family, Janet had accepted a marriage proposal from her boyfriend—the son of an Assemblies of God pastor—only to have him break it off months later and marry her (now former) best friend.

After this, Janet felt a sense of embarrassment everywhere she went, even around total strangers—as if they all knew about her getting dumped, and were whispering to one another about all the ways she was unlovable. She began obsessively criticizing her appearance in the mirror, hating her baby-fat cheeks, her short legs, her flat, brown hair—everything that, she believed, had caused her fiancé to call off their engagement.

Naturally, her mother was relieved at the breakup, not only because she was adamant that Janet get her four-year college degree before marriage, but because she hated the Assemblies of God Church. Hers was a Methodist, progressive family, and they all viewed the Pentecostal AG Church as politically conservative, as well as given to the bizarre rituals of speaking in tongues and falling to the floor. Also, for many young people in the late 1970s, Assemblies of God was usually the first church they’d attended that incorporated rock music, along with modern fashion and language, into their services.

While her classmates snuck out of the house to do drugs or have sex, Janet snuck out to attend the AG youth group. Even now—as Aretha Franklin sang “God Bless America” at the inauguration—Janet disguised a copy of Time magazine within her biology textbook, so her mother wouldn’t see what she was reading. The cover image of the magazine looked like a poster from a Haight-Ashbury concert, full of clouds and psychedelic colors. “The Jesus Revolution,” read the headline, above a picture of the man himself, neither white nor olive-skinned, but fluorescent pink. The story about a wave of California hippies who had renounced drugs and were getting high on Christ was five years old, but, like most trends that begin on the coasts and slowly work their way to the Midwest, the Jesus Revolution had finally come to Mason City, Iowa.

She’d been given the magazine by a friend from the AG youth group, who’d recently moved to Iowa from Los Angeles, where she’d attended Calvary Chapel, the Pentecostal church that was the epicenter of this new Christian-rock scene. In the last few months, Janet had been pressing her friends at AG for any information they had on the born-again hippies, obsessively writing down the names of books, bands, and lecturers for her to track down.

By the late 1960s, the counterculture generation spawned in California was becoming disillusioned with its own hedonism and in need of a reset. Between 1967 and 1971, over half a million young people left their homes to join experimental communities throughout California (captured in the melancholy Beatles song “She’s Leaving Home” and Scott McKenzie’s syrupy “San Francisco”). Many of them flourished, but others were hotbeds of drug addiction, poverty, disease, and the sexual abuse of young women. By 1971, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, and Brian Jones had all died at the age of twenty-seven from drugs and alcohol. Charles Manson had turned the hippie identity into one of night-stalking terror. And at the Rolling Stones free concert outside San Francisco, the Hells Angels beat dozens of audience members with weighted pool cues before stabbing and beating one of them to death.

“So flower power didn’t work,” John Lennon said. “So what? We start again.”

Whether it was Leonard Cohen and William Burroughs embracing Scientology, or Sammy Davis, Jr., and Jayne Mansfield joining the Church of Satan, there was a rich marketplace of spirituality for California bohemians. And, for many, the answer was Pentecostal Christianity.

Arguments abound as to who started what would come to be called “the Jesus Movement”—led by “Jesus People,” or “Jesus Freaks” if you ask cynics like Hunter S. Thompson—but it can largely be traced back to two events: the recording of the song “I Wish We’d All Been Ready,” and the acid trip of a gay, naked hippie who spoke to God.

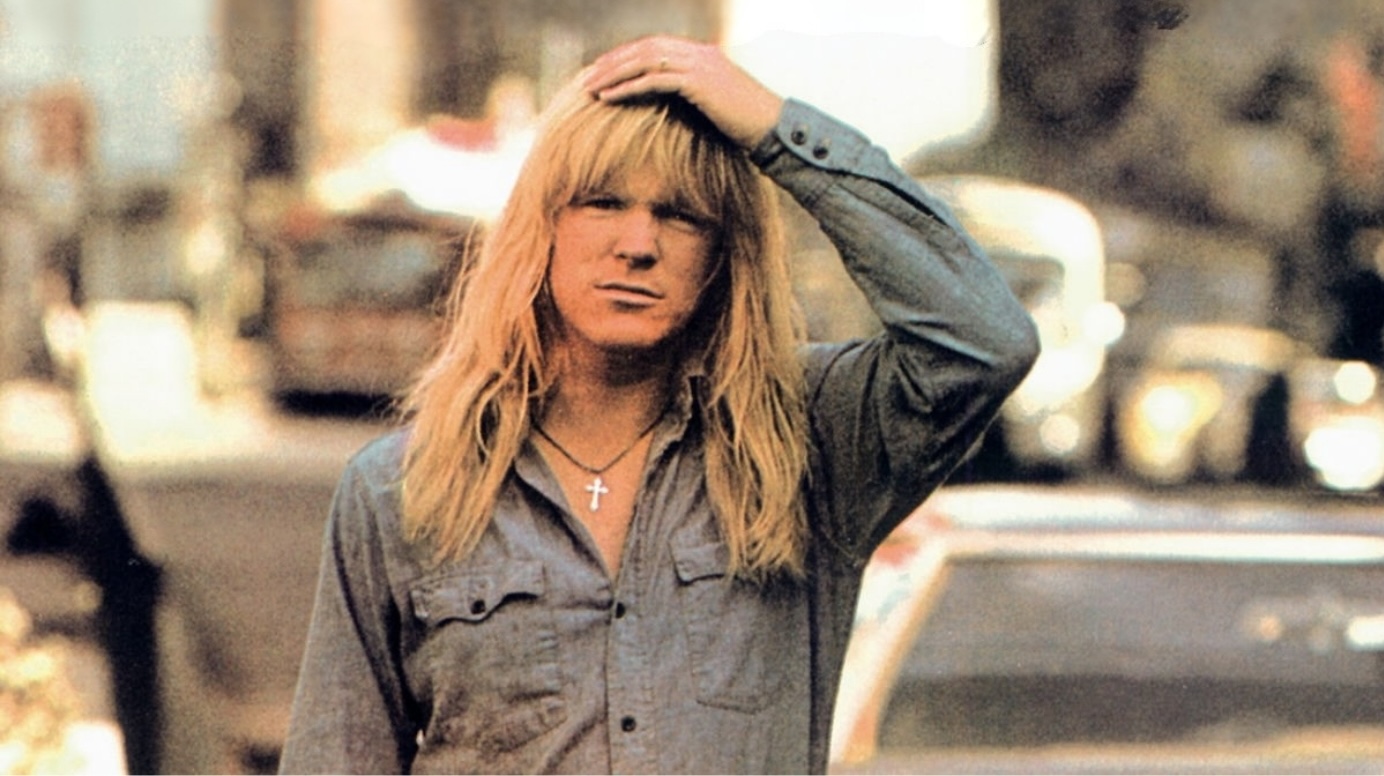

Larry Norman was a struggling rock musician living in L.A., opening for A-list acts like The Who and Jimi Hendrix, when he struck upon an idea: Why not blend the feverish, apocalyptic messages of the Black Pentecostal Church he was raised in (despite being profoundly white, almost an albino) with modern rock music? After all, every rock-and-roll pioneer from the fifties—from Ray Charles and James Brown to Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis—stole his act from the wild Pentecostal services of his youth.

His debut album, Upon This Rock, didn’t sell many copies and would lead to his getting dropped from Capitol Records in 1969, but would go down in history as the first Christian rock album. The album’s macabre rapture anthem, “I Wish We’d All Been Ready,” depicted the apocalypse of Revelation through a series of haunting vignettes set in the modern age. Not only would it become the “Blowin’ in the Wind” of the Jesus Movement, but, decades later, the song would inspire a series of wildly successful Christian novels depicting the events of the Apocalypse, particularly the line “you’ve been left behind.”

Janet had heard the song played almost every week at the AG youth group, and though she was as convinced as anyone that the end-times prophecies of Revelation were legitimate, she bristled when people would tie them to a specific date. Both in California and Iowa, many Jesus People were certain the events depicted in Larry Norman’s song would occur in either 1981 or 1988. But, unlike most of them, Janet was a student of history, aware that every generation of Christians since the death of Jesus has had elaborate theories as to why his return was imminent.

While it may seem like these Christian hippies should’ve gravitated toward the social gospel of Jimmy Carter, the doomsday prophecies and distrust of government preached by conservative fundamentalists jibed well with the Jesus Freaks.

In addition to Larry Norman, Janet had heard a lot of talk about Lonnie Frisbee, the handsome hippie prophet leading the Jesus Freaks of California into the promised land. Rumors of his sexual proclivities hadn’t yet made the trip to Iowa.

Frisbee was a teenage runaway hiding out in San Francisco’s flourishing gay scene, and it wasn’t uncommon for him, high on LSD, to read aloud from the Bible to the men he’d just slept with. During a particularly rowdy acid trip, Frisbee wandered into the California desert, stripped naked, and demanded that God reveal himself. Frisbee recounts feeling bathed in warm light and then having had a vision of himself leading thousands of hippies into the Pacific Ocean to be baptized.

That prophecy materialized little more than a year later, as the street-preaching Frisbee launched the House of Miracles commune in Costa Mesa, alongside struggling preacher Chuck Smith of Calvary Chapel. Thanks to Frisbee, Smith’s church went from a dozen retirees to thousands of barefoot believers. Calvary became the epicenter of the scene, launching Christian rock bands like Love Song and Children of the Day.

For years to come, Frisbee and Smith would baptize hundreds of converts every Sunday at Newport Beach.

“People tell me I look like Jesus,” Frisbee said when appearing on Kathryn Kuhlman’s TV show, I Believe in Miracles, referring to his long hair, the flowing fabrics and leather sandals he wore, and his beard, “and I can’t think of anyone I’d rather look like.”

This look wasn’t relegated to the Jesus Movement scene. As any photo of John Lennon, Kenny Loggins, or Gregg Allman in the early seventies will attest, Jesus was one of the most influential forces in fashion at the time, as well as in pop culture.

Musicals like Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar were dominating Broadway, and songs like The Doobie Brothers’ “Jesus Is Just Alright” and Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit in the Sky” rebranded the stuffy, pious Jesus of their parents’ generation into a groovy peace activist. The Christian hippies were even name-checked in the novelty country song, “Convoy,” which spoke of “eleven long haired Friends of Jesus / In a Chartreuse microbus.”

Frisbee’s sexual behavior was somewhat of an open secret in the scene, but Calvary Chapel grew into an international organization (eventually blossoming into a network of eighteen hundred churches), and Frisbee was fired for being gay. He would die of AIDS in 1993, though initially the reported cause was a brain tumor.

The internal conflicts of the Jesus Movement weren’t reported in the Time article Janet was reading, but in the second magazine she was given by her friend from California—an issue of Life magazine from 1972—the story of wealthy conservatives co-opting a movement of idealistic, DIY hippies was all there, if you read between the lines.

The cover read “The Great Jesus Rally in Dallas,” and inside were pictures of a hundred thousand Christian hippies crowded into the Cotton Bowl Stadium. Many of them were holding their index fingers in the air, a popular gesture among Jesus People meaning “There’s only one way to Heaven”—i.e., Jesus. (Fifty years later, it would become the salute of QAnon followers at political rallies.) Janet marveled at the size of the crowd in the pictures: the number of Jesus Freaks in Mason City could hardly fill a sanctuary. Though the event had taken place five years earlier, it felt more contemporary than anything in Janet’s life.

The Explo ’72 festival, a six-day conference of live music and lectures for young Christians, is known as the culmination of the Jesus Movement—even though they really had little to do with it. Acts like Children of the Day, Larry Norman, and Love Song would perform, but the event was organized by Billy Graham and Bill Bright’s Campus Crusade for Christ, which preached the virtues of conservative Christianity to college students across the nation. Bright would go on to co-found the Alliance Defending Freedom, a right-wing legal advocacy group that would labor to end abortion access and LGBTQ rights.

“The Jesus Movement was certainly courted by conservatives, even though we didn’t realize it at the time,” remembers Marsha Stevens-Pino, who performed at Explo ’72 with her band, Children of the Day. (Stevens-Pino spoke with me over the phone in 2023.) “We were made to feel special, these kids who’d been disparaged by the media, and in our homes. We were outcasts, and now we were made to feel like we were on the inside of something. And Explo ’72 was really a launching point for a lot of political people to cash in on us, because it was an election year and we were now of voting age.”

Many conservative evangelists, like Jerry Falwell and Jimmy Swaggart, denounced Christian rock, but Billy Graham saw Explo ’72 as an opportunity to evangelize to young people about the dangers of sex and drugs, and why America is the greatest country on Earth. He called it “a religious Woodstock,” but many of the original Jesus Freaks refused to participate because of its affiliation with right-wing groups like Campus Crusade. Though the dissenters were in the minority, as this was the direction the movement was headed.

While it may seem like these Christian hippies should’ve gravitated toward the social gospel of Jimmy Carter, the doomsday prophecies and distrust of government preached by conservative fundamentalists jibed well with the Jesus Freaks.

“The Jesus People didn’t leave counterculture behind; they thought that adopting fundamentalism was to swim upstream,” says Brad Onishi, a religious scholar and the co-host of the Straight White American Jesus podcast. He also spoke with me over the phone in 2023. “Back then, mainline Protestant churches were seen as the establishment; they were the ones that helped give us the New Deal, helping build the Great Society. The Jesus People viewed them as ‘The Man,’ as they had the money and power, they were the ones who got invited to the White House.”

This was what drew Janet away from the Methodist Church her parents had raised her in—with its pews, hymnals, and stained glass—and toward the Assemblies of God Church, with its young people playing electric guitars while sporting bell-bottoms and denim vests. AG leadership had denounced rock and roll throughout the fifties and sixties, only to embrace it by the late seventies, when it proved to be an effective recruiting tool for young people.

Though Jimmy Carter was technically an “evangelical,” his brand of evangelizing—caring for the poor, showing compassion to your enemies, striving for world peace—would, in the years ahead, be replaced with a new kind, one that would forever alter the meaning of the word in the public consciousness.

Janet closed the issue of Life magazine and quietly slipped it into her backpack before her mother could notice she wasn’t reading about biology. Her sneakiness was unnecessary, however: her parents’ attention was still fixed on the TV, and they beamed with pride as Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter danced together at the inaugural ball.

Carter may have been known as the leader of “the New South” (promising an end to the racist terror of Dixie’s past), but after Janet read about the Jesus Movement of California and reflected on the scene at the AG youth group, the Democratic Party that her parents had been championing for as long as she could remember suddenly felt very old.

She could relate to the hippies’ feeling that they were dismissed by society, and was experiencing the same draw toward the new conservativism of Bill Bright and his Campus Crusade for Christ. That would certainly give her a bond with her older siblings, and give her mother something to worry about beyond her grades.

Suddenly academia didn’t have the same shine for her it once had.

Janet no longer wanted to be a diplomat, and wasn’t even sure about college.

A new scene had arrived in Iowa, and she was determined not to be left behind.

__________________________________

Excerpted from On Fire for God: Fear, Shame, Poverty, and the Making of the Christian Right – a Personal History by Josiah Hesse. Copyright © 2026. Available from Pantheon Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Josiah Hesse

Josiah Hesse, author of Runner’s High and the Carnality series, is a freelance journalist out of Denver, Colorado, covering everything from politics, science, and crime, to art, pop culture, and evangelical culture and theology. A regular contributor to The Guardian and Vice, his work has appeared in Esquire, Newsweek, Men’s Health, and Politico, among other publications.