How The Exorcist Turned the Tensions Beneath the Inviolable Nuclear Family Unit into Horror

Kelly Roberts, Michael Grasso, and Richard McKenna on the Patriarchy Beneath the Possession

One of the biggest movies of the 1970s, The Exorcist is probably best known for the public response to its shock and blasphemy. Aping the sensationalist marketing of B-movies from the 1950s (like William Castle’s famous gimmick films, such as 1959’s The Tingler—electric shocks dealt from every cinema seat), ubiquitous TV and newspaper stories about the film during its holiday season release detailed the audience’s visceral physical reactions of disgust and abjection: moviegoers were passing out, vomiting, screaming in terror.[1]

Lapsed Catholics spoke of the film’s evocation of their pre-Vatican II haunted childhoods,[2] while church officials were scandalized by the gross-out horror and sexual blasphemy of Linda Blair’s child possessee Regan MacNeil.[3] In the film-academic world, contemporary critical response to The Exorcist was negative, and sometimes even vitriolic. Film Quarterly’s Michael Dempsey called it a “trash bombshell” that expertly appeals to both “reactionaries” as well as liberal “sophisticates” and “ruthlessly manipulates the most primitive fears and prejudices of the audience.”[4]

Dempsey and others look at the mania surrounding The Exorcist as evidence of a rapidly diminishing capacity for the contemporary American (and by extension Western) film audience to discern fantasy from reality, a condition expressed in both the personality cults and religious movements, new and revivalist, sweeping the country in 1973.[5]

Ruth McCormick, in Cinéaste, offered a more measured and detailed review, and unsurprisingly it is her feminist critique that gets at the misogyny at the center of the film:

The Exorcist can be seen as an extended rape fantasy. It is a sadist’s delight, and the repellent torture of an innocent young girl by an unseen, powerful male entity cannot but be a real turn-on to brigades of woman-haters unable to find happiness even in the sado-masochistic porno flicks in which the women seem to enjoy their degradation […] I have also heard and read more than one male opinion that Regan’s ‘possession’ is due to her awakened sexuality, with the definite implication that, at the age of 12, she needs a man and not just a daddy.[6]

So much of the criticism and analysis of The Exorcist over the past half-century has focused on the possession of Regan as an expression of her transition from childhood into adolescence that it’s easy to miss what McCormick was able to see right away, living as she was in a milieu where the hard-won struggles of women’s lib were encountering what Susan Faludi would later call a “backlash.” Are Regan and her mother, film actress Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn), being punished by Blatty and Friedkin for being independent women who not only are without a “daddy” figure in the aftermath of the Sixties, but perhaps don’t even need or want a daddy?

In our first look at the MacNeil family, we watch matriarch Chris go into Regan’s bedroom to shut a window. It’s Regan’s room that looks more like a home’s traditional master bedroom, with its fusty, old-fashioned decor (including, apparently, a full china cabinet), while Chris’s bedroom is tiny with a childlike bed, decorated with little-girl touches like lace pillows and patterned wallpaper. Chris has a whole staff of household helpers: a cook, a handyman, a personal assistant, and Regan’s upper-class childhood is idyllic at the outset, full of horse rides and picnics by the Potomac.

Mother and daughter seem very close despite all of Chris’s professional engagements; they giggle about their appearance on a Photoplay magazine cover, taking Chris’s wealth and fame in stride. It’s during a bedtime conversation that we see glimpses of the family dynamic that has put mother and daughter together: “You’re gonna marry him, aren’t you?” Regan asks teasingly, referring to film director Burke Dennings (Jack MacGowran, who will later be flung by the possessed Regan down the film’s infamous Georgetown stairs). Chris and Regan’s father, we find out, are divorced.

The sensationalistic and uncanny horror in The Exorcist has its roots in the quotidian and homely, as does Regan’s compulsive cursing and acting out, the symptoms that lead her into a battery of invasive medical tests, and eventually priestly treatment for demonic possession. On the phone with the operator on Regan’s birthday trying to reach Regan’s father, Chris rages at his overseas absence as Regan peeks from her bedroom: “He doesn’t even call his daughter on her birthday, for Christ’s sake! He doesn’t give a shit!”

The folkways and practice of divorce in America were going through a sea change in the early 1970s. Fittingly enough, considering Chris’s Hollywood career, California set the new nationwide standard, passing the Family Law Act of 1969, which enshrined no-fault divorce.[7] Other states soon followed. Prior to this, American married couples who wished to separate had to use esoteric loopholes to prove harm (or go to states or abroad to other countries that offered quickie divorces).[8]

The push to establish divorce laws that would allow for unilateral separation was part and parcel of the feminist movement. However, laws and customs that overwhelmingly protected male material interests in both marriage and divorce were already long on the books, and it soon became clear that husbands would benefit far more from these new laws than wives. Men were established as breadwinners; divorced women who had been housewives often found themselves with the short end of the stick as alimony and child support laws lagged behind.

As the Seventies moved on and divorce rates skyrocketed across America, a new awareness of a structure half-built began to sink in among feminist scholars and legal minds: systemic disadvantages in the workplace and in American society’s financial and social infrastructure left divorced women incredibly vulnerable.[9]

Tensions that had simmered under the surface of the inviolable American nuclear family unit throughout the Fifties and Sixties—housewives trapped in their homes, children chafing at “father knows best,” feelings of meaninglessness among those fathers in their grey flannel suits—could no longer remain hidden.

In the world of Hollywood, of course, divorce was and had been a regular fact of life for decades, fueling the gossip rags and movie magazines. Ronald Reagan himself, who signed the Family Law Act as California governor, was notably divorced from first wife Jane Wyman and would go on to become America’s first divorced and remarried president ten years later.

The wealthy movie stars in Hollywood’s studio system were provided with all kinds of “fixer” infrastructure to prevent difficulty in their various personal and sexual relationships: secret abortions,[10] “beards” for gay and lesbian actors,[11] and the smoothing of actors’ divorce and remarriage prospects. Chris MacNeil clearly possesses all the material benefits of a Hollywood actress—a beautiful Georgetown rental property and servants to help bear the burden of single motherhood while shooting on location.

The rot in the MacNeils’ home is therefore a spiritual rather than a material one, and Chris and Regan, despite their economic class, are exemplars of any single parent and child we might see in a Seventies film, from Ellen Burstyn’s own follow-up role as a widow in Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) to the decade-ending Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), which examined American divorce from the husband’s point of view.

American audiences were riveted a few months before The Exorcist’s release by a documentary series that aired on the then-new Public Broadcasting System. Titled An American Family, it told the story of a comfortable middle-class California family, the Louds: patriarch Bill, wife Pat, and five children ranging in age from their early to late teens. Cameras and filmmakers documented the Louds’ movements over the course of a few months in 1971 and ended up being present for the nominal disintegration of the formerly model suburban household: Pat demanded a divorce from Bill, and eldest son Lance came out as gay.

Intimate, real portrayals of these formerly taboo topics—divorce, homosexuality, familial disintegration—were aired to an audience of millions, who were already reeling from the societal changes wrought by the younger generation over the previous five years. Tensions that had simmered under the surface of the inviolable American nuclear family unit throughout the Fifties and Sixties—housewives trapped in their homes, children chafing at “father knows best,” feelings of meaninglessness among those fathers in their grey flannel suits—could no longer remain hidden. This breakdown is explicit in The Exorcist.

It makes perfect sense to consider Regan’s foreboding introduction of a Ouija board and her imaginary friend “Captain Howdy” as the gateway to her eventual possession: in her review, McCormick notes that her macho male chauvinist moviegoer “will see perfectly that Regan turns to Captain Howdy in the first place because she needs her Daddy.”[12] And however one classifies Regan’s preternatural empowerment, it’s that inherent need for a father that ultimately leads to her torment.

This point comes to the fore when the medical and psychiatric establishment—science itself—can do nothing to cure Regan, and Chris must turn to Catholicism and the patriarchal power of both Church and priests for a “cure.” In Friedkin’s and Blatty’s schemas, it’s the power of God the Father who saves Regan, and the priests, celibate and unmarried, serve as surrogate father figures, although they can never take the place of the man who doesn’t call on Regan’s birthday.

Both stern Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) and the young, tortured priest Damien Karras (Jason Miller) see their own personal psychodramas finally resolved through their intercession with Regan and battle with the Devil, but at the cost of their own lives. In a conversation between Karras and Merrin at the height of the exorcism process, Karras asks, “Why this girl?” And Merrin responds, “I think the point is to make us despair. To see ourselves as animal and ugly. To reject the possibility that God could love us.”

*

[1] Typical of these well-marketed audience interviews and reactions is “The Exorcist | Audience Reactions.” YouTube, uploaded by The Exorcist Online, 24 Mar 2014, youtube.com/watch?v=AkIqFK3KoZ4. See also Dempsey, Michael. “The Exorcist.” Film Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 4 (Summer 1974), p. 61.

[2] Dempsey, “The Exorcist,” p. 62

[3] McCormick, Ruth. “‘The Devil Made Me Do It!’: A Critique of The Exorcist.” Cinéaste, vol. 6, no. 3 (1974), pp. 18-22, p. 21.

[4] Dempsey, “The Exorcist,” pp. 61-2.

[5] McCormick, “‘The Devil Made Me Do It!’”, p.19.

[6] Ibid, p. 21.

[7] For more, see Gough, Aidan R. “Community Property and Family Law: The Family Law Act of 1969.” Cal Law Trends and Developments, vol. 1970, issue 1, pp. 273-305.

[8] Friedman, Lawrence M. “A Dead Language: Divorce Law and Practice before No-Fault.” Virginia Law Review, vol. 86, no. 7, Oct 2000, pp. 1497-1536, pp. 1504-5.

[9] For more, see Melnick, Erin R. “Reaffirming No-Fault Divorce: Supplementing Formal Equality with Substantive Change,” Indiana Law Journal: vol. 75, issue 2, pp. 711-729.

[10] Bianco, Marcie and Merryn Johns. “Classic Hollywood’s Secret: Studios Wanted Their Stars to Have Abortions. Vanity Fair, 15 Jul 2016, vanityfair.com/hollywood/2016/07/classic-hollywood-abortion.

[11] Morgan, Thad. “When Hollywood Studios Married Off Gay Stars to Keep Their Sexuality a Secret.” History.com, 10 Jul 2019, history.com/news/hollywood-lmarriages-gay-stars-lgbt.

[12] McCormick, “‘The Devil Made Me Do It!’”, p. 21.

___________________________________

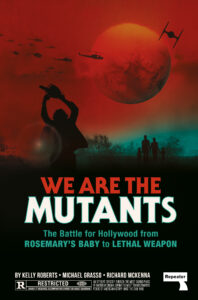

From We Are The Mutants: The Battle for Hollywood, from Rosemary’s Baby to Lethal Weapon by Kelly Roberts, Michael Grasso and Richard McKenna, available from Repeater Books (UK) and Penguin Random House (US).

Kelly Roberts, Michael Grasso, and Richard McKenna

Kelly Roberts is editor-in-chief of We Are the Mutants and a freelance writer. He lives in Boston. Michael Grasso is a senior editor at We Are the Mutants, a freelance writer, and a museum professional. He lives in Los Angeles. Richard McKenna is a senior editor at We Are the Mutants and a freelance writer and translator. He lives in Rome, Italy.