How the Barbizon Gave Sylvia Plath and Joan Didion Freedom and Creative Autonomy

Paulina Bren on Life at New York's Most Famous Women’s-Only Hotel

Joan Didion, who would become known as one of the finest writers and chroniclers of America’s political and cultural shifts, checked in to the Barbizon in 1955. She arrived, just like Sylvia Plath had, with a drawer full of prizes and awards and a reputation that suggested great things were to come her way. She had received the enviable telegram from Betsy Talbot Blackwell, but so too had Peggy LaViolette, one of her closest friends at the University of California, Berkeley.

It was unusual for the magazine to choose two students from the same university, but Joan and Peggy were delighted to have each other along for the ride. As sophisticated as they felt, they were both California natives after all, and in Peggy’s words, their circle was limited to WASPs, girls dressed in “cashmere sweaters, and skirts, and saddle Oxfords, with shiny hair.” They knew little of the larger world.

Flying to New York, it was Joan Didion’s first time on an airplane. It was 1955, late May, and air travel was a pleasure and not yet an ordeal. Flights had names as if to suggest they were the start of a journey. Their American Airlines flight was called the Golden Gate, and it was taking them from San Francisco to New York. Didion was only 20 years old, very small and fine-boned, with dimples and light brown hair cut to just above her shoulders. It was much the same hairstyle Sylvia Plath had worn two years earlier when she traveled to New York as a guest editor. As for Peggy LaViolette, this was not her first trip in an airplane (she had flown the summer before to Mexico City), and she became the unofficial expert as Joan gripped the seat.

The stewardesses, as they were called then, served the passengers Beltsville roast turkey with dressing and giblet sauce. Apparently it wasn’t only flights that had names back then; turkeys did too. The Beltsville was an invention of the 1930s—a turkey that was finally small enough to fit an apartment-size oven. As Joan and Peggy leaned over their roast turkey, they made sure not to spill. Both had dressed up for the plane ride, as was expected of any airline passenger in those days. Peggy’s mother had insisted that she go to San Francisco’s best store, I. Magnin, for her travel suit.

Upon entering, they made a beeline for the “moderate” floor. It wasn’t “couture,” one floor up, where they seldom ventured, but nor did it mean thumbing through the racks. The “moderate” floor came with a “clothing adviser,” who greeted Peggy’s mother by name, led them over to a damask-covered love seat, and asked Peggy to describe the purpose of her outfit. She was going to New York, she explained, for the month of June, staying at the Barbizon and working in the Mademoiselle magazine offices on Madison Avenue. She would need to appear sophisticated while she mingled with editors, advertisers, and the New York literati.

Nodding, the clothing adviser disappeared behind a mirrored door and then reappeared with an armful of items that she spread out on the love seat. Peggy, her mother, and the clothing adviser put their heads together, touching the fabrics, remarking on the cut and style, until the outfits were narrowed down to those worth trying. Peggy left I. Magnin with a navy two-piece dress in summer wool: a long tunic top that buttoned up the front and a pleated skirt underneath. There was even a detachable white collar.

With lunch over, the stewardess passed out postcards. One pictured a DC-7, the same airplane that they were on; another some passengers toasting the flight over cocktails in the airplane lounge. This was in-flight entertainment in the 1950s: the opportunity to write to friends and family to let them know you were flying high up in the clouds. But once the postcards were written, the boredom of sitting took over, as did the droning of the metal carcass in flight. The Golden Gate stopped twice along the way, dropping off some passengers and picking up others.

Peggy’s desire to buck the trend was as intense as the pressure to conform.

In Dallas, Peggy and Joan got off and bought a boxed meal while the plane refueled. Next was Washington, DC, and with it being Friday of Memorial Day weekend, the plane now filled with congressmen. The final leg of the trip to New York was by far the worst, and Peggy sat next to a quivering Joan, reassuring her that the air bumps did not translate to imminent nosedives, even as she was losing faith herself.

Joan Didion was a junior at Berkeley, and had another year of college left, but Peggy was a senior missing her graduation, which her mother had found difficult to process. What her mother did not understand, no matter how much Peggy had tried to explain, was that there wasn’t a girl in America who wouldn’t choose Mademoiselle over her graduation ceremony. New York beckoned as California receded, and Joan and Peggy confided to each other how they were glad to be free of their boyfriends (Joan would take hers back upon returning to Berkeley, even as she felt their relationship was “hopeless,” leaving her “bored” and “apathetic”). Peggy felt little loss in leaving her boyfriend behind, was in fact perfectly content without him, but the pressure to have a “steady” was intense. As a college senior over the past year, Peggy seemed to spend almost every weekend at some friend’s wedding—checking off yet another girl who had dropped out of Berkeley to accompany her new husband to Fort Benning for his mandatory military service.

Peggy’s desire to buck the trend was as intense as the pressure to conform. Her parents had reared her to work: her mother had always had a job, and in the early years, her father, a teacher, thought nothing of spending summers at the local pea cannery to supplement their income. (Even so, one day, as Peggy was helping dry dishes, her mother turned to her: “Peggy, you know you don’t have to stay at Cal all the way through. You ought to be able to find a husband in two years.” The rest was all noise and haze: Peggy began to shout at her mother that she loved Berkeley and why would her mother suggest she prostitute herself?!)

When Peggy graduated from Berkeley High in 1950, most of her friends received a hope chest as their graduation gift. A cedar-lined chest filled with linen guest towels and bedsheets. Peggy didn’t want a hope chest, she wanted a typewriter, preferably an Olivetti portable typewriter with a travel case. Joan Didion turned up at Berkeley with that very typewriter and travel case; moreover, as Peggy enviously learned, Joan had gotten hers without a fight. Now they both carried their typewriters onto the plane with them. A handbag in one hand, and gripping their typewriter in the other.

To try to be who they were, or who they wanted to be, was not easy. The United States was at war again—first Korea, and now slowly Vietnam was beginning. The Cold War fears with which George Davis had grappled, lobbing accusations of female ambition at Cyrilly Abels, were being inflamed all the more. The solution for most women was retreat. The feminist Betty Friedan, in her famous book, The Feminine Mystique, would write that this era was marked by women’s “pent-up hunger for marriage, home, and children,” “a hunger which, in the prosperity of postwar America, everyone could suddenly satisfy.”

America’s expanding suburbs were a witness to this, where one-income families and two-car garages were the new normal. The quiet rebellions against these values were inevitably individual, unassuming, and—in the case of Peggy and Joan—cashmere-clad. They carried their typewriters, boyfriendless, unencumbered, dressed in their cardigan sets, ready to tackle New York. Joan had already been picked as the guest fiction editor, the most prestigious of all the posts, and the one that Sylvia had so desired. Peggy would be guest shopping editor.

Both wore nylon hose and one-and-a-half-inch heeled pumps on the plane, but Joan had dressed more lightly in anticipation of New York’s summer heat; being from Sacramento, she understood hot weather better than Peggy. Nevertheless, when Joan finally got off the DC-7 at the Idlewild Terminal (as JFK International Airport was then called) in Queens, New York, she felt her new dress, chosen for this moment of propitious arrival, and “which had seemed very smart in Sacramento,” was “less smart already.” New York overwhelmed before it even came into full view.

There was, however, nothing “smart” and stylish about the bus ride from the airport to Manhattan. Joan opened the window wide “and watched the skyline,” only to see instead “the wastes of Queens and the big signs that said MIDTOWN TUNNEL THIS LANE.” But upon entering Manhattan, everything changed. Their first sighting of the towering skyscrapers and sidewalks crowded with people injected Joan with the “sense, so peculiar to New York, that something extraordinary would happen any minute, any day, any month.”

To try to be who they were, or who they wanted to be, was not easy.

When they finally arrived at the Barbizon on Lexington and 63rd Street, they looked up at the salmon-colored multiturreted building that they’d only before seen in photographs. Its architecture was a playful mixture of Moorish, Neo-Renaissance, and Gothic Revival styles but tastefully arranged in art deco lines and angles that had held up over the almost 30 years since it was built. Oscar, the doorman, stood at attention in his regalia.

Joan and Peggy entered the hotel lobby, the most impressive part of the Barbizon (the hotel keenly understood that first impressions mattered), and looked up at the mezzanine, from which groups of young women peered down, keeping an eye out for their dates or, just as likely, everyone else’s. Peggy and Joan went up to their rooms on the 14th floor, pleased to discover that theirs were adjacent to each other, at the end of the hall next to the elevators, and right next to the shared showers.

As per Mademoiselle tradition, on their beds they each found a single red rose and their itinerary for the month of June. But one thing had changed since Sylvia Plath’s stay at the Barbizon: now there was air-conditioning to ward off New York’s humid summer heat. Joan had caught a cold when she opened the window on the bus into Manhattan, and she would lie in her bed at the Barbizon for the next three days, curled up, fighting a fever, hating the air conditioner that was cooling the room to a wintry 35 degrees, unable to switch it off, too scared to call the front desk because she had no idea how much to tip if they came to help. It was better to freeze and save face. Instead, she called her on-again off-again boyfriend Bob, the son of the owner of Bakersfield’s Lincoln-Mercury dealership, and told him she could see the Brooklyn Bridge from her window. It was in fact the Queensboro Bridge.

*

That same day, guest editor and also future writer Janet Burroway was traveling in from Arizona. She called herself Jan because she thought this way she’d have editors guessing her gender (a feminist reflex before she even knew the word). She was a self-described “Arizona greenhorn,” but, like a protective shield, she carried with her to New York a preemptive world-weariness. She wrote to her parents—almost as if she were yawning into the page—that her first-ever airplane ride was “exciting and beautiful” and yet “surprisingly unamazing.” In fact, it turned out to be exactly as she had imagined it: she could pick out her college dorm as they flew over Tucson and “the rockies looked like a salt and soda map, the midwest like a gigantic patchwork quilt, and Lake Michigan like an ocean.”

But just as happened to Joan Didion, the mask that Janet had carefully prepared fell away as soon as the plane touched down in New York. Janet had planned to look “cold and beautiful,” but upon arriving at the airport she was sure “that Arizona was stamped in neon letter[s] on my forehead.” Like countless arrivals to New York before her, she immediately felt “ALONE.” She stood bewildered in the middle of the terminal, unsure of where to go, standing in the way of others who did. Finally, she spied a young woman with a hatbox, and confident that anyone with a hatbox knew where they were going, she simply followed her through the concourse and onto a bus heading into Manhattan. It was only once she was on the bus, sitting across the aisle from her, that Janet saw her luggage tags: Ames, Iowa.

The bus eventually emerged from what Didion had called “the wastes of Queens” and deposited its passengers in Manhattan. Janet hailed a cab. As she sat in bumper-to-bumper traffic, the cabbie eyed her through the rearview mirror. Perhaps he saw that “Arizona” stamp on her forehead.

“New York,” he said, turning around to face her, “is like a big ice cream soda—try to eat it all at once, it nauseates you: a little at a time, it’s wonderful.”

She would soon learn just how right he was. Once checked in at the Barbizon along with all the other GEs, she took one of the hotel postcards out from the desk drawer in her room and wrote home: “Rm 1426—pretty far from the pavement.”

The next day she elaborated, dismissing the Barbizon’s “typical room” as it was featured on the postcard; it was bogus, a lie. Her room—a real Barbizon room—was in fact “brother’s-size and old.” She called it brother’s size because back home, in the middle-class, sunlit ranch house in Arizona, it was Janet who had the largest bedroom of everyone and she was used to space to move around in. Still, she had to admit the Barbizon itself was “beautiful, very impressive.” And even if one was quick to judge, as Janet Burroway was, it was impossible to deny the hotel’s pull, its mythology.

__________________________________

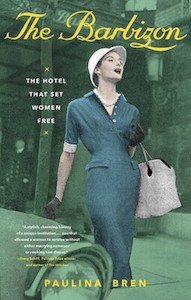

Excerpted from The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Paulina Bren.

Paulina Bren

Paulina Bren is an award-winning historian and a professor at Vassar College, where she teaches international, gender, and media studies. She received a BA from Wesleyan University, an MA in international studies from the University of Washington, and a PhD in history from New York University. She currently lives in the Bronx with her husband and daughter.