The Longest Year: 2020+ is a collection of visual and written essays on 2020, a pivotal year that shifted our way of experiencing the world. In most publications, images work in service to words—here they work in tandem. // In part two of the series, Marvin Heiferman reflects on the death of his husband, Maurice Berger, and processing the grief that followed. Photographs and text by Heiferman.

I never intended to make any of these photographs.

Since 2014, I’d been taking different sorts of pictures and posting one each day to Instagram. Photographs of odd but beautiful things, photographs about the nature and act of observation itself. The people who paid attention to them were, for the most part, fascinated with visual culture, people who like to look and think about looking: photographers, artists, curators, writers, editors, publishers. My husband, Maurice Berger, a noted cultural critic, was one of them.

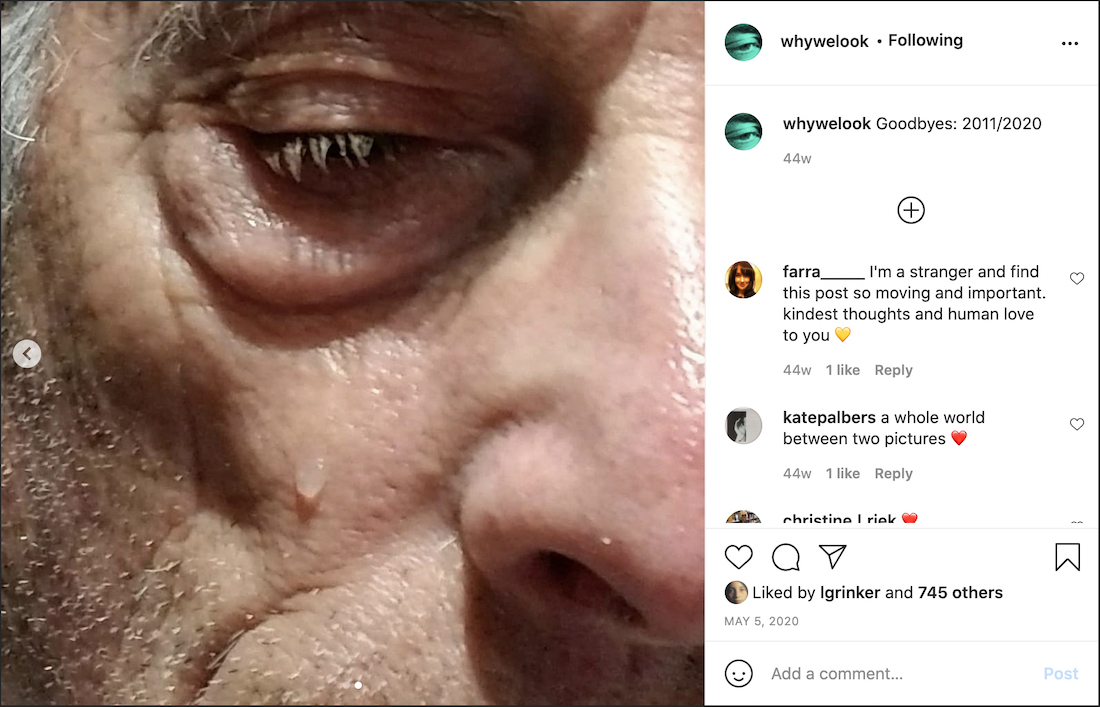

On March 12th, 2020, as COVID infection rates spiked and the death count in Manhattan was surging, Maurice and I decided to head to our house in upstate New York, where we thought we’d be safer. And we were, for a while. On March 15th, as we walked around the Roosevelt Historic Site in Hyde Park, Maurice took a picture of me taking a picture, which he captioned and posted it to his Instagram later that day: Marvin, not missing an opportunity to photograph something. It was the last photograph he would take. On March 16th and 17th, he was tired. On March 18th, he woke up with a fever. And as the sun set on March 22nd, I was alone in our car in a state of shock, staring at first responders standing idly by ambulances and the Medivac helicopter that Maurice, who had just been declared dead, never made it on.

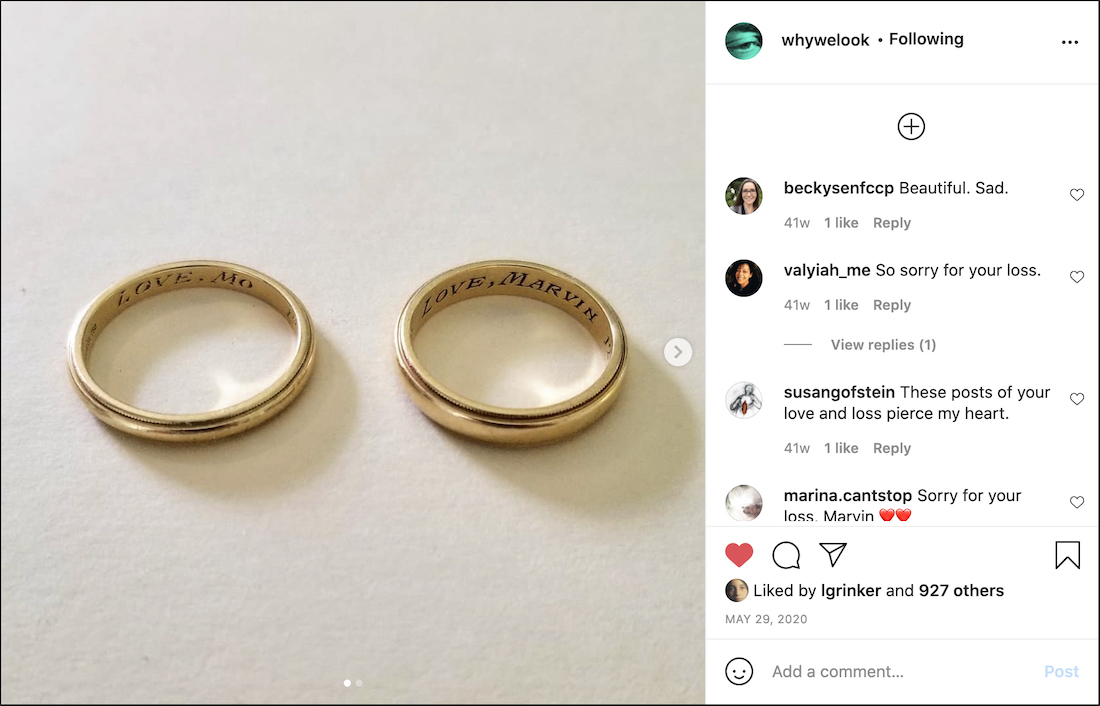

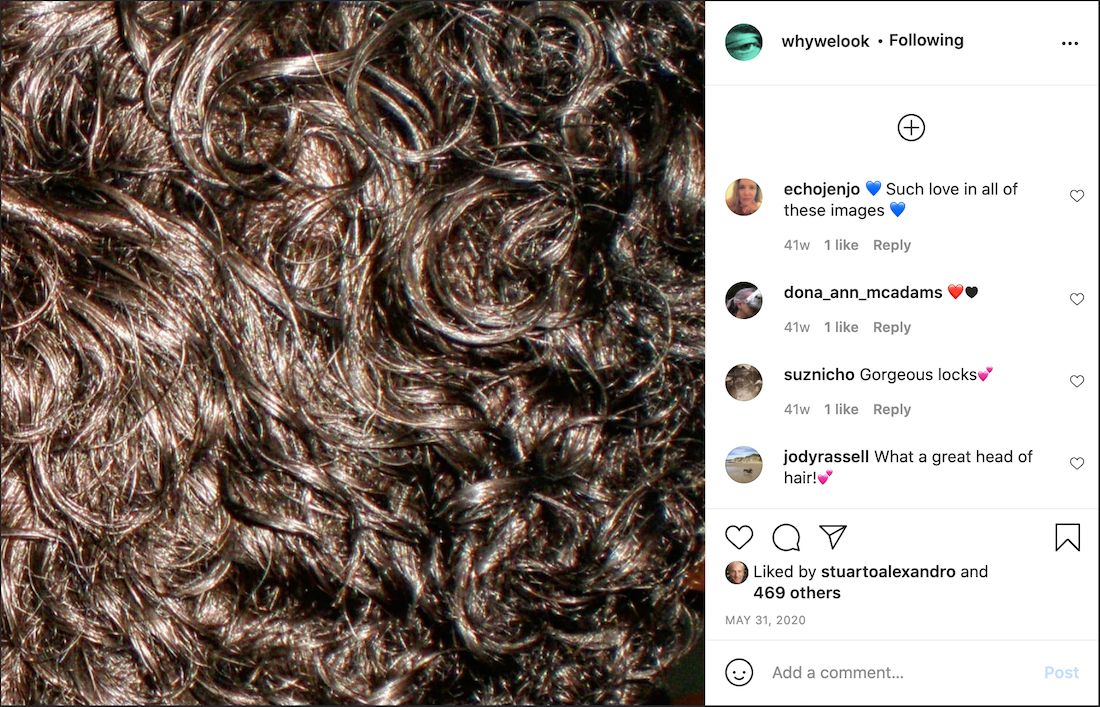

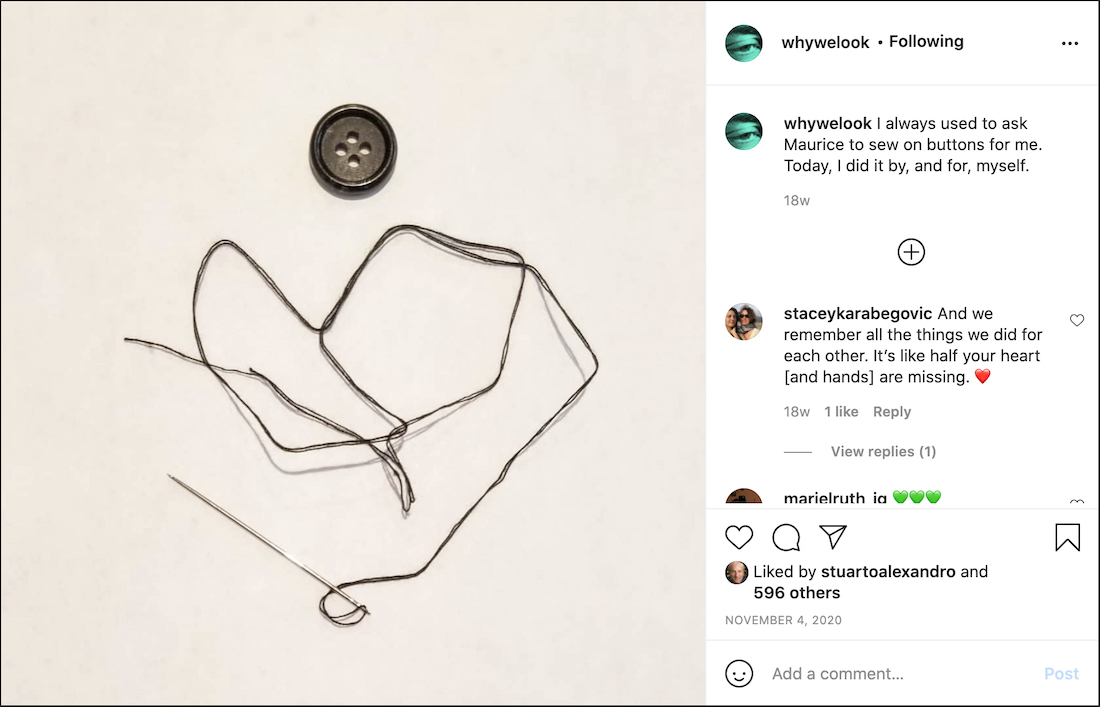

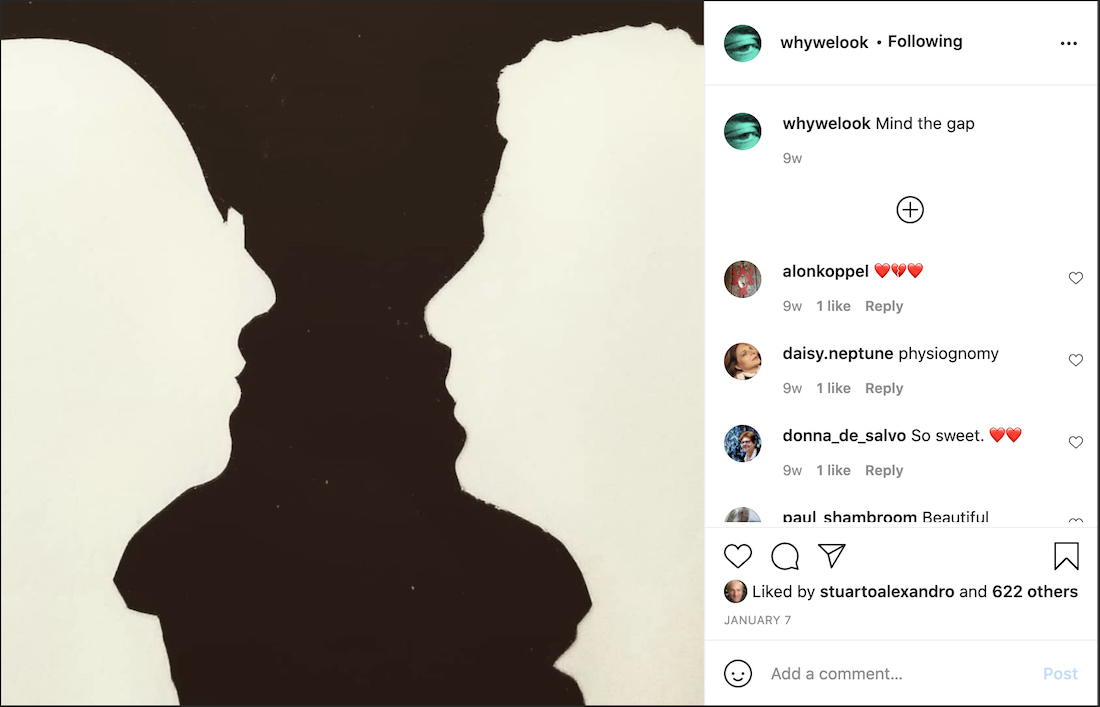

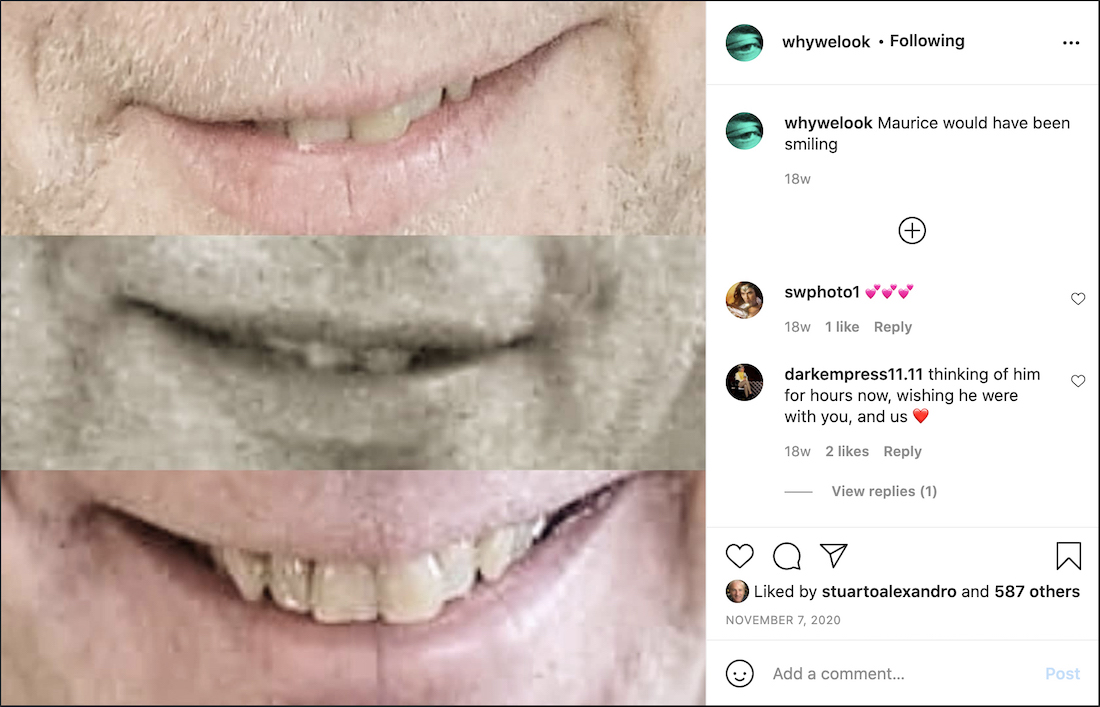

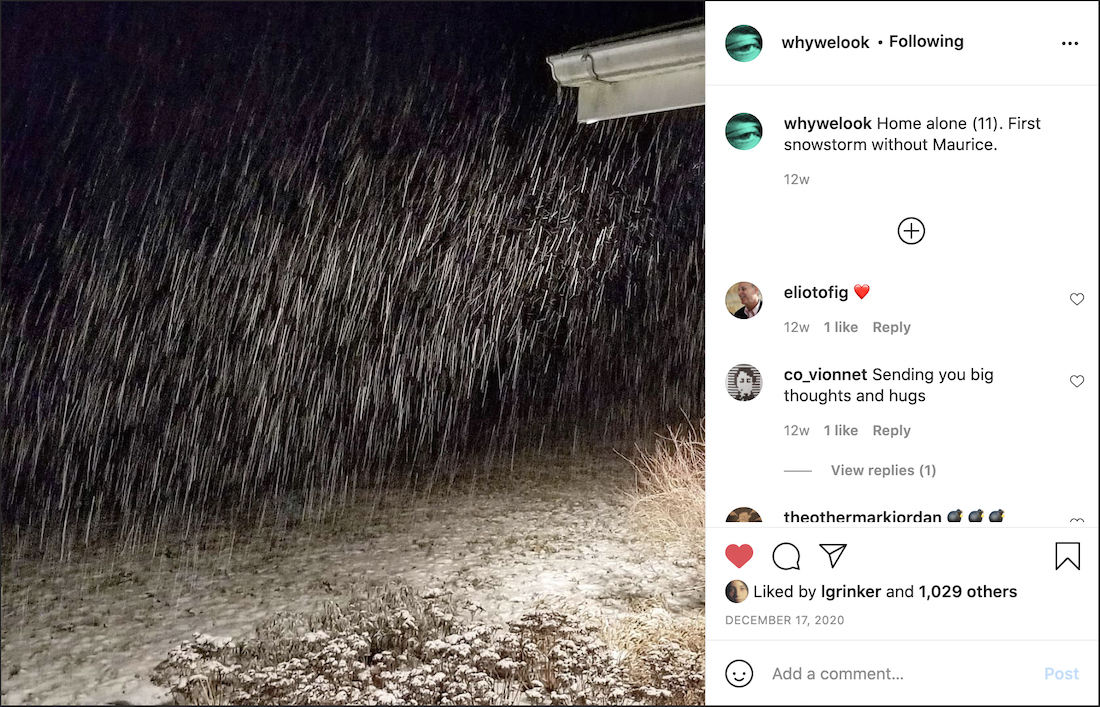

Maurice died of COVID-related illness but local elected officials were stonewalling me, refusing to swab or autopsy his body. I was dumbstruck by what had and was happening—freaked, bereft, isolated, inarticulate—and when words failed me, photography didn’t. On March 25th, I started to take and post daily pictures on Instagram again. While I was barely able to eat, sleep, or think straight, that was the only thing I felt I could accomplish which made sense for me. The kinds of pictures I was making, though, had changed; they visualized, in one way or another, the very vulnerable state I was in. And to my surprise, they started to resonate as others looked at and commented on them in numbers I was unaccustomed to, with unexpected kindness, empathy and concern. The pandemic was upending lives in multiple ways. Anxiety, fear and grief were widespread. And on a social media platform known for its relentless branding of happiness, I became a grief guy, posting images of my 24/7 sadness, confusion and the one-foot-in-front-of-the-other mode I was left alone to operate in.

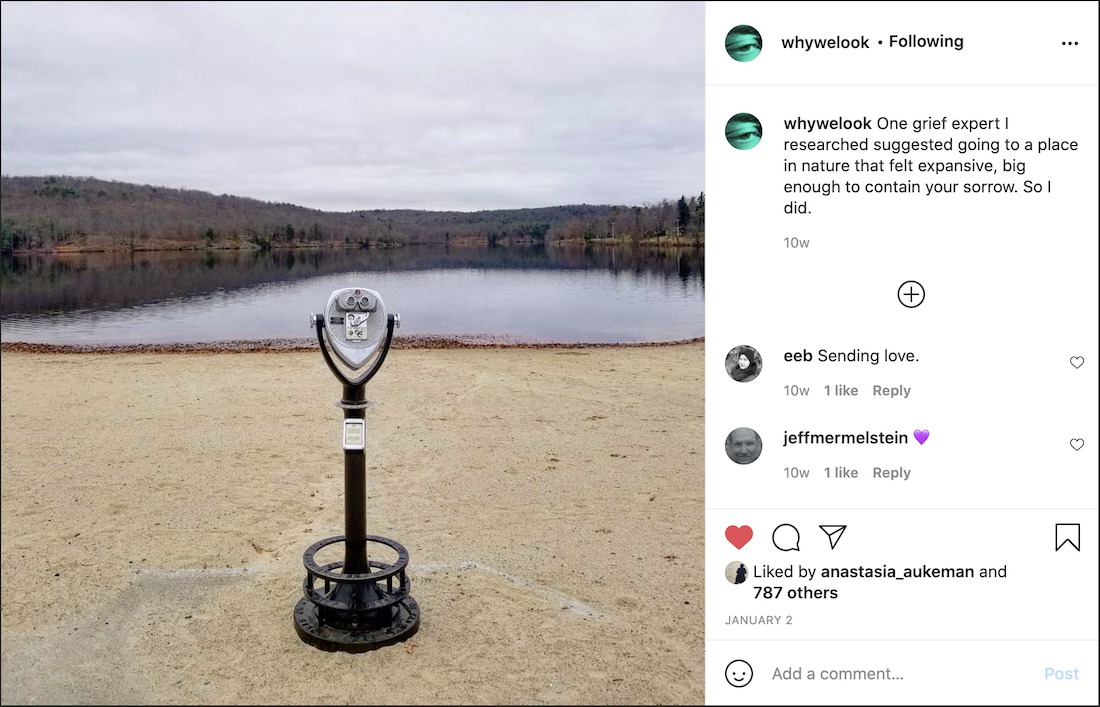

Grief experts talk about the fact that grief needs to be witnessed and they are right. The taking and sharing of photographs, in a world that turned scary and that locked down quickly, made a sense of community possible. Instagram gave me a place and structure to sort through what I was experiencing, startling and irrevocable loss, and to shape the heartbreaking sense of absence I was up against into some kind of presence. The picture-a-day regimen helped me confront my own vulnerability and gave me comfort and courage and a platform to share it with others. It helped me clear a path through the weeks and months when I, like others, lost track of time.

In this past year, I’ve come to understand that what I am doing is both telling a story about Maurice and me and one about photography, love, death, memory and politics. My life was turned upside down in what felt like an instant. But what’s been consistent ever since is how friends—and so, so many strangers—have responded to the pictures by reaching out to express their support, sending condolences and, in direct messages, sharing unflinchingly intimate stories of their encounters with loss. I’ve been changed and they’ve been touched by pictures in ways none of us could have imagined. For all the media coverage of the pandemic, there were people who still didn’t personally know anyone who’d died of—or whose life was upended by—COVID. Now, they did.

_________________________________

The Longest Year: 2020+ is a collection of visual and written essays on 2020, a pivotal year that shifted our way of experiencing the world. Edited by Rachel Cobb, Alice Gabriner, and Elizabeth Krist.

Rachel Cobb is a photographer who lives in New York City. She has worked for numerous publications including The New York Times, TIME and Rolling Stone magazine. Her award-winning book Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence was published by Damiani in 2018. More of her work can be found here.

Alice Gabriner is a visual editor, instructor and mentor with 30 years of experience at publications, including The New Yorker, The New York Times, National Geographic, and TIME. For the first two years of the Obama administration, she served as Deputy Director of Photography.

A National Geographic photo editor for over 20 years, Elizabeth Krist is on the boards of Women Photograph and of the W. Eugene Smith Fund, helps program National Geographic’s Storytellers Summit, and advises the Eddie Adams Workshop. She curated A Mother’s Eye for Photoville and CatchLight, and the Women of Vision exhibition and book.