How the Armed Services Editions Created a Nation of Readers

Brianna Labuskes on the Weaponization of Books During World War II

There was laughter coming from the foxhole between bursts of the Germans’ anti-tank guns. The American servicemen were in a tight position, pinned by the Boche, but they’d made it to an interesting part of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith and everyone knows how hard it is to put down a good book. The novel—being read out loud by one of the men—kept their spirits up even as they fought for their lives.

This was just one of thousands of stories from soldiers, foreign correspondents and military leaders that flooded into the Council on Books in Wartime praising the Armed Services Editions—lightweight paperbacks that were sent to the boys overseas during World War II. The audacious and revolutionary project became one of the Army’s best morale boosters, offering a bit of light during those dark days. It also helped shepherd in an era of paperback supremacy and create millions of voracious readers in the process.

Long before the Armed Services Editions were even a gleam in their creator’s eye, Hitler and the Nazis made books a cornerstone of their strategy in their march toward total power. The book burnings in Berlin—an event that is now indelibly tied to the death of democracy and the birth of fascism—were just a start. The Nazis went on to ban voices that could undermine their message; plunder vast research libraries to better understand “the enemy;” create a national book club that distributed Nazi-approved reading selections; and gift Hitler’s manifesto to every newly married couple in the country.

Books had become weapons in the war before there even was one.

The United States wasn’t about to let itself be beat on that particular battlefield, and its leaders fully embraced the idea that books were crucial to winning against the Nazis. President Roosevelt’s words—“books cannot be killed by fire”—were plastered all over propaganda posters, and it was General Eisenhower who made sure each of the servicemen storming the beaches in Normandy had a paperback Armed Services Edition in his pocket.

Books had become weapons in the war before there even was one.

Prior to the ASEs, though, the logistics of getting books into the hands of soldiers were tricky. The government tried a book collection drive, similar to how Americans were asked to scour their homes for any bits of tin and copper, but that brought in heavy hardbacks. While those could be used in libraries at the bases in the US, they weren’t exactly deployment-friendly.

To a modern audience, the solution to use paperbacks instead of the hardcovers might seem obvious. But the publishing industry is steeped in tradition and prestige, and there was a stigma attached to those soft covers.

In the thirties, paperbacks had a reputation and not a good one.

Booksellers snubbed their noses at the cheaper step-sibling of the illustrious hardback, the content was considered inherently trashy, and while a select few publishers found success with the soft covers, others were forced to close due to lack of interest.

War has a way of bringing about change, though. Both paper rations and budgets were tight in the forties, and it no longer made sense to rebuff the humble paperback.

Thus, the Armed Services Editions were born—the brainchild of Raymond Trautman, a young officer who headed up the Army’s Library Section; H. Stanley Thompson, a graphic artist Trautman roped into helping design the lightweight novels; and the Council on Books in Wartime, an organization made up of publishing professionals from librarians to authors and publishers.

The creators didn’t want to do things in half-measures. They didn’t want to just send drugstore paperbacks overseas, they wanted to design the perfect book for soldiers to carry into war. That meant designing the paperbacks to match the dimensions of an Army uniform’s pocket, it meant using two columns so as not to strain the soldiers’ eyes with long sentences and it meant creating vibrant covers so the titles were easy to see at a glance.

With the printing logistics taken care of, the question that was left was what books to send. The Council wanted to include a wide-range for the boys to enjoy—everything from classics to Westerns to literary fiction were included. The servicemen particularly liked both juicy, scandalous stories and the ones that reminded them of home.

The first shipment of the Armed Services Editions was sent in 1943 and they were an instant hit.

Bored yet terror-stricken men were hungry for entertainment and here was a feast. In her excellent non-fiction account, When Books Went to War, Molly Guptill Manning pulls highlights from the letters that soldiers wrote into the Council. The men confessed that they’d never before finished a book cover-to-cover but were devouring all the ASEs they could get their hands on. They talked about how the soldiers who are lucky enough to be first in line on delivery days ripped the paperbacks apart by chapter so that their brothers-in-arms don’t have to wait for them to finish the whole book. They asked for extra copies of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and Chicken Every Sunday because the stories remind them so much of the reason they’re fighting.

“They are as welcome as a letter from home. They are as popular as pin-up girls,” one GI stationed in New Guinea wrote in to the Council, according to a 1944 New York Times article featuring the ASEs.

The Armed Services Editions were instilling a reverence for books and a deep appreciation for stories in the minds of millions of men who would never have considered themselves readers.

After the war, you didn’t have to be a Rockefeller to build out a personal library.

This love not only carried them through the hardest days of the war, but followed them home. It made them seek out opportunities with the G.I. Bill where before they might have passed on the idea of more schooling.

While neither the Council nor the Army invented the paperback, the Armed Services Editions created an eager audience, stripped away the stigma and propelled that model into sustainable popularity.

In doing so, they helped remove some of the wealth barriers that came with buying books. Before the war, access to novels was limited. Even if someone was lucky enough to have a bookseller in town, the cost was prohibitive to the vast majority of people who had just lived through the Great Depression.

After the war, you didn’t have to be a Rockefeller to build out a personal library.

The ASE project had been inspired by the foundational idea that books were more than just paper and glue and stories to pass the time. They were a defiant symbol of freedom, a bulwark against fascism, a light in the dark. The pictures of the Nazis’ book burnings have lived in the public conscious for nearly 100 years because of just how powerful a symbol books are.

But there were times for many Americans when they were just that—a symbol. Admirable but unreachable. Through the help of the ASEs, the publishing landscape was nudged toward a slightly more equitable future.

Books were no longer just symbols of the land of the free—they could now actually represent a democracy that the men who had so fallen in love with reading had fought so hard to protect.

__________________________________

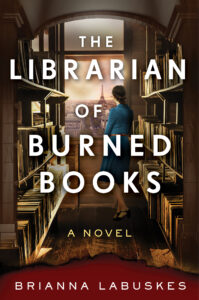

The Librarian of Burned Books by Brianna Labuskes is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Brianna Labuskes

Brianna Labuskes is the Washington Post bestselling author of five thrillers. For the first decade of her career, Brianna worked as a journalist for national news organizations covering politics and policy. Her new book, The Lost Book of Bonn, is now available.