How Teju Cole Helped Me Make Peace With the Nigerian Scam Artist

Ijeoma Oluo on Reconciling her Nigerian-American Identity

Teju Cole will be appearing at Town Hall Seattle as part of Seattle Arts & Lectures Literary/Arts series on Thursday, April 21st.

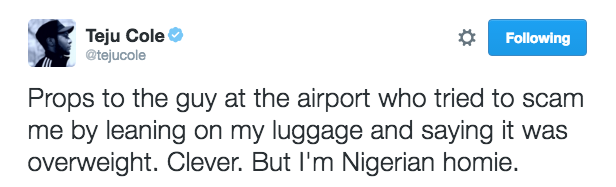

These words, popping up on my twitter feed, were the words that endeared me to Teju Cole forever. I’d long been a fan of Cole’s work. He has always managed to combine wit and empathy in a way that consistently challenges the reader and makes us grateful for the growing pains his work brings. His writing and photography never fail to shed new light on issues that we didn’t know were so very important. But in under 140 characters, Cole managed to reach my heart in a way that few writers have.

I was first introduced to the Nigerian scam artist at age 15. This was in the mid-1990s, when the internet was still largely populated by chat rooms. I was looking for my father. I was not looking for his address—I had that—or his phone number. I was looking for his life, his work, his words. My father, the Honorable Chief Dr. Sam Oluo, had gone back to Port Harcourt Nigeria before I turned 2. He kept in touch with my mother for a few months—a letter here, a call there—and then the communication stopped. From then on, my only knowledge of my father was filtered through my mother’s heartbreak. All that I had outside of my mother’s memories and a few fading photos, was an old copy of my father’s Political Science doctoral thesis on the Biafran War.

I come from a family of artists and musicians—creators who swim in the pools of their emotions. For a serious, quiet, humorless girl who can’t carry a tune, it was easy to feel out of place. I have obsessed over world events and political systems since I was a very young child. My first memory of needing to understand the way in which socio-political power works was when I came across a newspaper headline about the Tiananmen Square protests and crackdown in 1986, when I was five. This obsession was often viewed as morbid, or at the least, very boring, by the rest of my family. When I became a teenager and learned that I could make a career out of studying how political systems work, I was extremely excited. When I realized that my father had made a career out of the very same work, I felt like maybe I hadn’t just dropped out of the sky as a baby and landed in the wrong nest.

So here I was, in a Nigerian chat room, trying to find information about my father, and find a connection to his people. The response was immediately welcoming.

“Ijeoma! I have heard of you! I know your father. Everyone knows your father!”

“Ijeoma! I grew up with your father! What a great man.”

“Ijeoma! I just saw your father last week! He speaks highly of you to this day.”

I was beaming. I had a father and these people knew him. Even better, they knew me. The hole in my heart began to fill with a feeling of belonging I’d never before had. Soon they were offering to help.

“Your father has written many books here in Nigeria. I can get them for you.”

“I have access to your father’s papers. Just send the filing fees and shipping and I’ll send them your way.”

I was seconds away from sending all my babysitting money when a fellow Nigerian jumped in.

“Do not give any of these people your money! They will scam you! You don’t understand what it is like here in Nigeria.”

I was shocked, embarrassed, and hurt. My own people trying to scam me minutes after I had found them. It was a few years before I fully understood the legacy of colonialism that had contributed to an entire economy built on corruption; it was a few years before I would understand what people will do to get by. As I got older, I chalked up my ability to be scammed so easily to the fact that I was a kid at the time and took comfort in the fact that the most they would have gotten from me was a few nights of babysitting money.

As I got older, the Nigerian scam artist turned into a meme. The “Nigerian prince” became a joke tossed around by white people with the same ease that “Italian mobster” jokes were likely tossed around in the ‘70s—but aided now by the internet. Whenever I came across casual references to my people as scam artists, I’d wince. There was more to us than the scam. Hell—there was even more to the scam. But at the same time, I understood. I received the emails too, but when I did, there was a chuckle and a shake of the head that was filled with as much love as disappointment. Every white person scammed out of their life savings felt, in a way, like a bit of retribution for the ravages of colonization and slavery which had both robbed Nigeria of so much—even though I knew that the money wasn’t exactly going to feed poor children, and it wasn’t coming from rich, greedy capitalists.

That conflict—that embarrassment and disappointment mixed with unconditional love and a bit of pride—is something that Teju Cole has never shied away from. In his book Every Day Is For The Thief, Cole gives an unflinching look at the world of Nigerian scam artists, or “Yahoo Boys.” When interviewed about his feelings on the scams Cole said,

Of course it’s unfortunate when you actually meet somebody or you read about somebody who has been scammed, but there is something to be said for being a grown-up in the modern world who knows well enough not to get excited about offers of money from strangers.

In Every Day Is For the Thief, Cole is also able to set aside his fierce protectiveness of how Nigeria is portrayed to outsiders by focusing on a wayward Nigerian’s return home. The book’s main character finds himself exploited by friends and family, and surrounded by scam artists and corruption. I think that the unromantic nature of the Every Day is For the Thief is in part due to the fact that it was published in Nigeria first, and it feels like Cole was writing it for a Nigerian audience that understands the intricacies at work in the tale of the Nigerian scam artist. These stories do not seem sensationalized; they resonate with the anecdotes that many relatives and friends have shared upon their returns from trips home to Lagos or Port Harcourt. They’ve been robbed, scammed, threatened. But they were also home, with a family and a culture and an identity that doesn’t exist anywhere else. Many times I’ve seen relatives come back from Nigeria newly penniless and exhausted, swearing that they will never return—that Nigeria has gotten too bad. But within a year, they are all desperate to return “home.”

Reading Cole’s work, I feel like I can breathe a little easier in my Nigerian-American identity. I can let the conflicting emotions within me just be. I don’t have to reconcile the indignant American within me with the proud, scolding and protective Nigerian.

Reading Cole’s work, I feel like I can breathe a little easier in my Nigerian-American identity. I can let the conflicting emotions within me just be.

Last year, I received an email from one of the Yahoo Boys. I have gotten these in the past, as any westerner with email access surely has, and usually I just delete them without opening them. But this time, as the sender’s email name was a formal title that in no way matched the use of all caps in the subject line (“INQUIRY”), I decided to go ahead and read it. The email was a request to help move $18 million in capital from Nigeria to a bank in Thailand. For my participation. likely my bank account number and advancing some “wire transfer fees”, I would eventually receive 10% of the $18 million.

As I read the email, I was reminded of Cole’s tweet that had had such an impact on me. I was offended in the same way that Cole was—how dare he try to scam me—a Nigerian! Perhaps I was even more offended, because the scammer himself was also Nigerian. What type of fool did he think I was to not recognize the scam of my own people?

I replied back to the scammer. Scolding him for seeing the name “Ijeoma Oluo”—a name as Nigerian as Susan Smith is American—and trying to scam me out of my hard-earned money like I was any white lady. “Where is your loyalty?” I asked.

I thought that was the end of the conversation, but later in the day, I received a reply from the would-be scammer. One that reinforced my love of Nigeria and my fellow Nigerians:

Apologies, please forgive,

I was doing a mass email so I had no way of identifying noting your email name. I hope you have a great day. Bye