How Sylvia Plath Calls Out for Connection Across Time

Sina Queyras Writes in Conversation with “Lady Lazarus”

“Lady Lazarus” is one of the late October poems Sylvia Plath wrote in a burst, at Court Green, around the time of her thirtieth birthday. Like many of the poems in Ariel, this one is part rage, part self-talk. Biographer Anne Stevenson refers to it as “merciless self-projection”: more “assault” than poetry. “Lady Lazarus” is often read as an inevitable march toward the third, and final, suicide attempt. The lines “Dying / Is an art, like everything else. / I do it exceptionally well” seem to confirm this reading, as does the mention of the “third attempt” in the eighth stanza.

It is true that there had been two previous suicide attempts, and that Plath suffered from depression, but from the outset the tone in this poem is provocatively humorous—“I have done it again. / One year in every ten”—and filled with overstatement: “a sort of walking miracle . . . skin / Bright as a Nazi lampshade.” Later the lines “peanut-crunching crowd / Shoves in to see” are delivered with a derisive laugh, as the speaker is unwrapped in “the big strip tease”: a line that would come to describe a whole school of women’s writing. That she is alive is “a miracle,” yes, but why? Her own “life” knocks her out, but it is also a lark, she writes, echoing Virginia Woolf. “There is a charge / For the eyeing of my scars,” she states, “there is a charge” for seeing her heart, “It really goes.” This section seems to predict her own reception: the ghoulish dogs that Hughes describes trying to own a bit of the Plath legacy.

But are they trying to own? Or understand? Regarding the reference to enemy in the fourth tercet and “Herr Enemy” in the twenty-second, I point to a letter written to psychiatrist Ruth Beuscher on September 4, 1962, just over a month prior to writing “Lady Lazarus,” where Plath states “any kind of caution or limit makes [Hughes] murderous,” and later in the same paragraph she says this institution is prison: “the children should never have been born.”)

These gendered power dynamics are palpable in Plath’s poem: “I am your opus”; “I a smiling woman” “turn and burn.” We can’t help but try to fill in the life behind the mask. And it seems we readers were sensing correctly: in a letter dated September 22, Plath writes, “Ted beat me up physically a couple of days before my miscarriage: the baby I lost was due to be born on his birthday,” and later “he tells me now it was weakness that made him unable to tell me he didn’t want children.”* The rage, then, is not surprising: “Beware / Beware” she writes, “out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.” While the poem ends with the speaker rising up, she is not yet out of the fire: she still has to eat her way through the patriarchy. I read this ending as a declaration of war. I read it as a will to live.

While Plath herself is not actually able to rise up out of the ash, her poems do.

I wrote my version of “Lady Lazarus” in what was one of the coldest winters in Montreal in many decades. Submerged in a converted closet with two toddlers bouncing overhead I juggled my anger like sticks of dynamite as the #MeToo movement simmered.

. . . I like a direct hit as long as it’s abstract. Come,

Come into my pink bath, I am floating, my ambition is not pretty.

My feeling is not a good colleague. I am not your affirmation machine:

My unpredictability is epic. I am all up in my body. I shrivel for you,

I undo all I have eaten, I pour myself into the ether and look, look.

There is no shit having it all. Once the rains come there is no

Having it all. You will or will not cut off your own head,

You will or will not get through this coldest year of your

Life, the season of your disagreement is a lengthy sentence.

My first attempts were long lines that spilled over, loosely falling into off-kilter couplets. I wanted to keep what I loved in Plath: the mid-Atlantic syntactical swagger, the humor, but I suspected that Ariel was as much a rejection of form as it was a declaration of war. I ran “Lady Lazarus” through a randomizer over and over again to rid it of any evidence of Plath’s rhythms but also to try to find a connection between her voice and mine:

You men, you have it all and raw. They say

The only gold left to pan is buried deep

In shit. I will relish you right up inside me

And at my leisure. I will take the baby teeth and songs

Of happiness. I am no lady. I am scorching air.

You can eat my genius, rare.

I settled on tercets because there are many in Ariel (“Morning Song,” “Elm,” “Fever 103,” “Gulliver,” Nick . . . ,” “Ariel”) and likely not a coincidence: those little tercets of “Lady Lazarus” tore the veil off of lyric propriety. To my version I added a dose of joyful Steinian resistance. Like Plath’s my tercets thrive on anger and bask in quick connections and sounds like knife wounds: “an umlaut in a grim gown” or “Not a lucky cut. No lucky strut, you.” There was also the physical element “where your legs pivot I swan my neck limp.” I wanted to conjure up the way in which the difficulties of a new mother trying to find her power might feel continually buffeted (“so gentle where the will bent”): continually distracted by others’ needs and demands.

When I found out that Ted Hughes had cut and shaped Ariel into a sequence that made Plath’s suicide inevitable, it felt not only like an act of self-protection on his part but also a final literary violence on her “corpus.” My poem enacts this violence. The speaker is continually buffeted: she makes statements, feels shame and recrimination, she is “threaded with old hurt” she will “shrivel for you,” she is abject, she tries to speak and causes shade, she is “off script,” even her feminism needs a good slap. She is also very aware: “I fell for a wolf don’t think I didn’t know my bones would be gnawed.” This self-awareness illustrates the ongoing cycle of what I think of as “aborted awakenings.”

I cling to reports of Plath reading “Lady Lazarus” with the joy of a woman released. I read the poem as victorious in the sense that while Plath herself is not actually able to rise up out of the ash, her poems do. In a letter to his sister Olwyn in 1962, Hughes described Plath as a “death-ray.” I suspect that what he was describing was not so much her as her ambition. Her drive. Her desire for a parallel career. For women, the price of a literary career has been far too high, far too long. For Plath, the cost of that parallel career was her life.

__________________________________

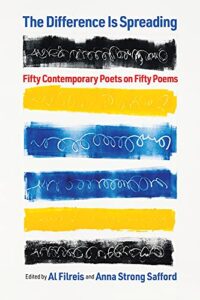

Excerpted from “Sina Queyras on Sylvia Plath, ‘Lady Lazarus'” from The Difference Is Spreading: Fifty Contemporary Poets on Fifty Poems edited by Al Filreis and Anna Strong Safford © 2022 University of Pennsylvania Press. Reprinted with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sina Queyras

Sina Queyras grew up on the road in western Canada and has since lived in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, New York, and Philadelphia. They are the author most recently of the poetry collections My Ariel (Coach House 2017) and MxT (Coach House 2014) winner of the Pat Lowther Award and the Relit Award for poetry. Their previous collection of poetry, Expressway (Coach House 2009), was nominated for a Governor General’s Award and a selection from that book won Gold in the National Magazine Awards. Lemon Hound (Coach House 2006) won a Lambda Award and the Pat Lowther Award. They are also the author of the novel Autobiography of Childhood (2011), shortlisted for the Amazon.ca First Novel Award. In 2020 they co-edited A Nicole Brossard Reader, and in 2005 they edited Open Field: 30 Contemporary Canadian Poets, for Persea Books. They are the founding editor of lemonhound.com, which ran from 2005 to 2018. Queyras has taught creative writing at Rutgers, Haverford, and Concordia University in Montreal. They have been Director of Concordia University’s reading series, Writers Read, since 2011.