How Similar Are the Hot, Historic Summers of 2020 and 1968?

Lee Weiner, One of the Chicago Seven, on Finding Hope for the Future

The early spring of 2020 saw defiantly unmasked, gun-toting crowds loudly demanding state legislatures and governors not close anything down because of the virus. A month or so later millions of people took to the streets much more loudly to chant their demands for racial justice after the police murder of George Floyd. The massive, extraordinarily widespread demonstrations against systemic racism in cities and towns all across the country were loud enough that some elected officials heard at least part of what was being shouted at them.

It’s possible that the convergence this year of a pandemic surpassing 150,000 deaths, the related economic breakdown and disaster for millions of working people, the legitimate anger and social unrest on the streets, and a presidential election might change America.

In 1968 there were especially loud people in the streets and it did help change the country. Resistance against a brutal, senseless war in Vietnam kept bringing people out to protest. Then the assassination of Martin Luther King brought still more people and rage and anger and fire to cities across our country. Later that same year, in Chicago, I and a few thousand friends and acquaintances were back on the streets demonstrating against the war, for an end to racism, and for a more equitable and just society. It was also a presidential election year.

There are plenty of similarities between then and now. This spring, the mostly nonviolent eruption of long suppressed rage against racism—the denigrations, brutalization, horror, and killings—is much the same as it was 52 years ago. Four hundred years is a very long time to be punished for the color of your skin and the glorification of white supremacy. And sometimes the process of rising up against oppression isn’t pretty and shouldn’t be expected to be polite. But a major difference between then and now is the vast number of white people on the streets alongside people of color in these important and necessary demonstrations that are sometimes dangerous to the people demanding change.

The rioting after King’s murder and the DNC protests in Chicago helped convince Richard Nixon to run for president on a “law and order” platform.On those Chicago streets during the Democratic National Convention in August 1968 I was clubbed and gassed by enraged, violent and brutal police determined to punish young people who were just as determined to fight for social justice and an end to the war.

Now as then, police use their clubs and gas against people who are on the streets demanding positive changes in America. But this time local police are more openly joined by militarized federal agents to threaten, hurt and arrest people—raising more clearly than ever the struggle between a growing, more inclusive democracy and a threatened state authoritarianism.

The rioting after King’s murder and the DNC protests in Chicago helped convince Richard Nixon to run for president on a “law and order” platform and to spread a divisive message to the country while claiming he wanted to unite it. It worked then; not by much, but it did work. Clearly, when Donald Trump denounces “radical left-wing cultural revolutionaries” and threatens to use the military, existing laws, executive orders, and any other force at his command to silence protests and protect statues of slave owners and the display of Confederate battle flags, Trump is betting on the same strategy Nixon used.

But here’s the thing—we’re in a different time. There have been far more people out on the streets than there were before, and even larger numbers of people are now apparently convinced, or at least ready to listen to the possibility that there is something fundamentally wrong; that something needs to be changed in the way the police and the powers of government are used to systematically oppress and punish people of color. And that those actions make a mockery of the positive values and promises of America, and distort and shatter our own hopes and aspirations for what our country and our lives might and should become.

As we did all those years ago, people today are hoping for something better. In the 1960s some of the initial prompts that helped move the people I knew to act personally to help change America came in response to images on TV and the newspapers of Black students and communities bravely fighting against segregation. Now people are being similarly moved after seeing images of police violence and murders, neo-Nazis marching and chanting against immigrants, Blacks, and Jews, and of innocent people left hurt and dying on the streets because they were willing to act against the hate and ugliness and brutality.

My friends and I were very far from perfect, and surely much of the ugly polarization between Americans now is rooted in the cultural and political struggles of the ‘60s. Then there were people of color, uppity women, a rising LGBTQ movement, university students, the poor, and all sorts of people saying and doing and demanding all sorts of things. And from all that noise and political work came some positive changes—none of it was complete, much of it perhaps still vulnerable to reversal—but there was change.

Some of those changes have helped make people stronger and freer, and the work itself provides a nearby history lesson that resistance to unjust government power and racism is possible and absolutely required. Those past times can also suggest some things that might still work politically today, and surely some things that didn’t work then, and most likely won’t work now.

Far better than we ever did in the 1960s, people now are working together. But what we managed to accomplish did help form a new social and political context.We learned our internal conflicts and arguments about the legitimacy and importance of local issue organizing, electoral politics, peaceful mass protests and righteous violence didn’t make one or the other illegitimate. Though in my old world the unbridged differences between otherwise allies—people of different colors, cultures, genders, classes, sexual identities—and all the competing claims on priorities for action helped shatter our movement.

Far better than we ever did, people now are working together. But what we managed to accomplish did help form a new social and political context, where the most recent blatant displays of racist ugliness and threats have led many more people to a revitalized sense of the necessity of personally acting to achieve a better country. And both then and now people were putting their bodies on the line for justice.

I’m in my 80s now. In my life I have been fortunate enough to live and work for many years among brave men and women who dedicated themselves to the struggle for social justice. Nowadays I sit and watch the news from around the country, seeing a resurgence of mob- and state-sponsored assaults on racial and social justice.

And while I am at times consumed by frustration and anger that many of the same battles for equality still need to be fought, I also feel immense joy at the numbers of people on the streets now willing and able to do the fighting—one of my own daughters among them. I hope and believe that the direction people’s politics will now take us is towards a more nurturing, safer, more equitable world for ourselves and our children.

__________________________________

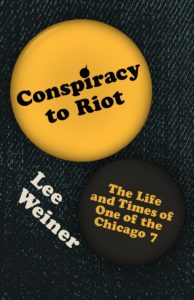

Lee Weiner’s political memoir, Conspiracy to Riot: The Life and Times of One of the Chicago 7, is available from Belt Publishing.